You’ve likely had the experience of having to Google a certain topic numerous times before you actually commit the fact you wanted to memory. Or maybe you have a certain piece of information stored in your email or your smartphone’s contacts that you constantly have to look up on your device every time it’s needed. This phenomenon is called “transactive memory”: By entrusting information to outside sources, like a smartphone or a book or even a close friend, our brain fails to prioritize the act of memorizing that information.

While this effect has been known for some time, a new study has found we’re actually fooling ourselves into believing this addictive nature makes us smarter. According to an article in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, we give our own minds credit for what the Internet knows, even if we haven’t committed online content to memory. “Searching for answers online leads to an illusion such that externally accessible information is conflated with knowledge in the head,” claims the researchers. Every time you find a fact online, your brain convinces you it’s learned the information even when it hasn’t, leading to “a systemic failure to recognize the extent to which we rely on outsourced knowledge.”

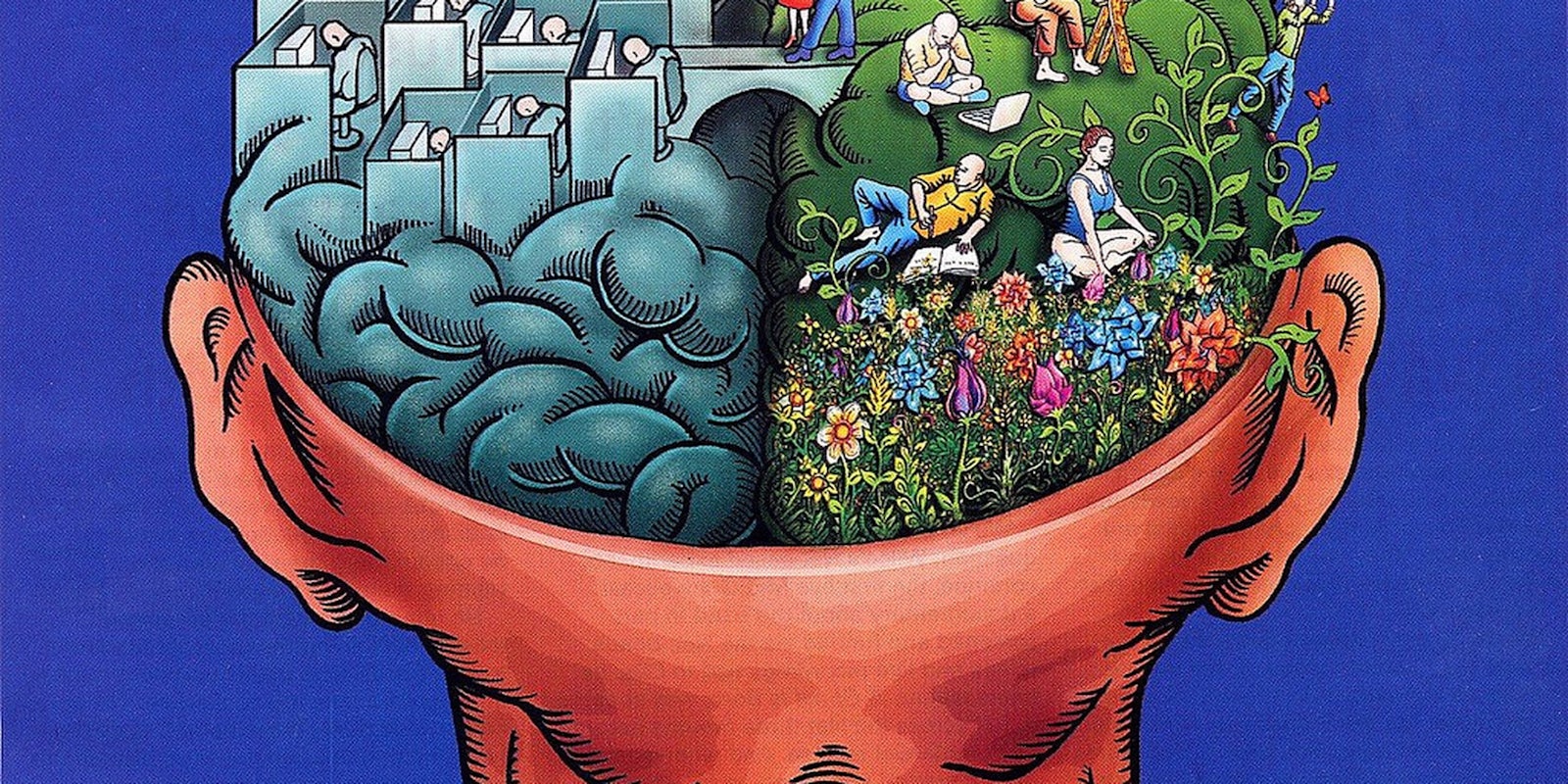

So not only is our digital memory making us less likely to use our own brains, but it’s also convincing us of the opposite. When you learn a vital piece of information, your brain attempts to store it. But as long as a rectangle in your pocket can tell you your sister’s phone number, the capital of Paraguay, and how to get to the nearest Chipotle, your brain retains less and less information, making you dumber as the machine gets smarter.

There’s a desperately underused method to counteract this effect that has worked wonders for my own memory as well as improving my attention span and my ability to focus on a tasks at hand: handwriting. Taking handwritten notes is scientifically proven to improve your memory for information both factual and conceptual, as well as boosting your creativity and advancing your everyday cognitive functions. While largely becoming a lost art in most schools, handwriting could be the solution to the our digital devices robbing us of our intelligence and convincing us otherwise.

Every time I go online at home, whether it’s to work, plan a family vacation, or play games, I make sure to have one of several composition notebooks—the black and white kind you used to write really bad poetry in—near me, so I can pull it out and write in my own words what I’ve read, what I’ve learned, and how many grandmothers I had to sell in order to afford a prism on Cookie Clicker. What it produces is not just a comprehensive journal of my online habits, which comes with its own benefits, but a mental gym for tackling ideas and concepts my mind would otherwise never bother with. It creates a space free of distraction to work over stories I run into on the Internet, the motherlode of distractions.

The effect of the Internet on our cognitive ability has certainly not escaped notice. It was celebrated by Wired’s Clive Thompson back in 2007, who praised the Web as an extension, not a replacement for, our organic brain. “The perfect recall of silicon memory can be an enormous boon to thinking,” wrote Thompson. “The machine helps me rediscover things I’d forgotten I knew.”

Nicholas Carr—in his famed 2008 essay “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”—felt the opposite of Thompson; he argued that the very business model of companies like Google is aimed at making our intelligence more fleeting and our attention spans less static. “The last thing these companies want is to encourage leisurely reading or slow, disconnected thought,” writes Carr. “It’s in their economic interest to drive us to distraction.”

Predating Thompson and Carr by several millennia is Socrates, who once wrote vehemently against the brand-spanking-new technology of writing. In his Phaedrus, Plato recounts how Socrates felt writing “will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory” and called it “an elixir not of memory, but of reminding.” But aside from the oral tradition of the ancient Greeks, writing might be the best tool to save the seemingly lost art of remembering things without having to google them.

My personal system for remembering what I read online relies very heavily on the cognitive benefit of handwriting above tapping away at a keyboard. In a comprehensive study last June, researchers out of UCLA found college students who jotted down notes by hand retained far more information than those who recorded them on a laptop, especially when it came to concepts over facts. According to the study, laptop notetakers took more notes but mostly transcribed the words of a lecture verbatim, never molding the facts and ideas expressed through their own filters.

Handwriters, however, found themselves expressing their own thoughts through their transcription, retaining a better memory for the facts and the concepts they represent. “Although more notes are beneficial, at least to a point,” write the researchers, “if the notes are taken indiscriminately or by mindlessly transcribing content, the benefit disappears.” So merely copying information does not lead to true learning; one must express the facts and ideas they encounter into their own words.

The answer to why handwriting has such a powerful effect on the brain’s memory relies on an understanding of how our brain processes the act of writing. In a 2010 study from Norwegian researcher Anne Mangen and French researcher Jean-Luc Velay, the brain is far more heavily influenced by the “haptics” (meaning the experience of touch and movement) present in writing than it is by the experience of typing. According to Mangen, “0ur bodies are designed to interact with the world which surrounds us. We are living creatures, geared toward using physical objects.”

Similarly, an Indiana University project found that grade school children’s cognitive functions were significantly increased by the act of writing out letters. While a keyboard does leave an imprint on our memory, it’s nowhere near as big as the imprint left by the complex actions necessary to form letters with a pen or pencil.

Far from simply being a study tool for college students, this should be a life skill for anyone that uses the Internet to learn about the world around them. While we’re encountering more and more information than humans ever have the capacity to process, we’re actively retaining less of it. By simply taking notes—something I realize not everyone will find as fun as I do—you’ll remind your brain what it’s like to not have the crutch of a smartphone in your pocket. Like a student way over his head, we need to change what we do with the massive amounts of information we glean from the Internet if we can ever hope to wrestle control of our memory away from it.

Photo via Pink Persimon/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)