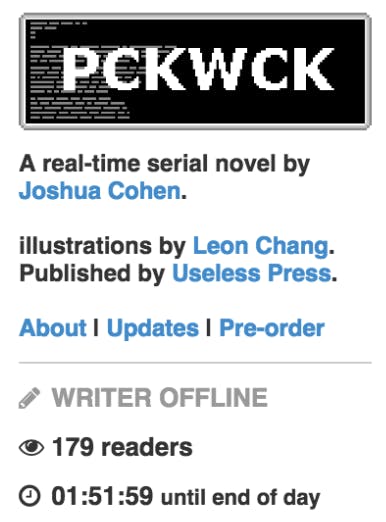

From Monday to Friday this past week, from 1pm to 6pm each day, Joshua Cohen has been writing a novel

on the Internet in real time.

Viewers at PCKWCK.com could comment, “heart” text as on Periscope, answer survey

questions, and watch a tiny livestream camera of Joshua Cohen as he wrote and edited his

story, a cigarette usually dangling out of his mouth—Hunter S. Thompson living in a Brooklyn basement.

I met with the author, who also wrote The Book of Numbers, on Thursday night after one of his

sessions. “The entire thing is written under duress. It’s getting tortured out of me. I mean it’s

exhausting,” he said. And so I asked him why he was doing it.

“Because it’s my worst fear. It’s an ego-building experience with the hope of destroying ego; it’s

a vanity-building experience with the hope of destroying vanity. And I’m a person who does not

like to be scared by anything, and I always ask why I’m scared. And the answer of why I was

scared of this just seemed that I should and could reckon with it.”

By Friday night, the project was over. The tiny square that had previously displayed the writer in

progress is now a still, fuzzy image with the text “VIDEO UNAVAILABLE.” After the final

countdown, a jaunty, celebratory tune played over the site. The novel, or art installation, or

experiment, or whatever it was, is complete

“Working for newspapers, which I used to do—what I saw when the ’90s turned into the 2000s was you’d have to write more pieces, more quickly, for less money. So the idea is a commentary on that.”

“There’s no chance it’s a good novel,” Cohen said. “There’s no chance it’s a bad novel. It’s not a

novel. It’s what happens when you take a culture worker who is under time constraints trying to

present himself as a symbol of a culture worker under time constraints. Working for

newspapers, which I used to do—what I saw when the ’90s turned into the 2000s was you’d

have to write more pieces, more quickly, for less money. So the idea is a commentary on that.

The huge volume of communications we have to deal with constantly, and how they’re

destructive and overwhelming and impossible to deal with.”

PCKWCK was framed as a rewriting of Charles Dickens’ famous serialized novel,

The Pickwick Papers, but aside from a few clever allusions (PCKWCK, “formerly BCC: BOZ

Conflict Consulting” is a reference to Boz, Dickens’ pen name), the connection isn’t immediately

obvious.

“I had the idea that I was going to rewrite Pickwick Papers,” Cohen began before correcting

himself, “base it on Pickwick Papers, but bear in mind, the original Pickwick Club being

wealthy British gentlemen who go out galavanting through the British countryside in pursuit of

knowledge and they really end up wreaking havoc and having fun, accompanied by their ever-so-charming serving class—my idea was to do that, and they were military contractors, kind of

galavanting around the world, making problems.”

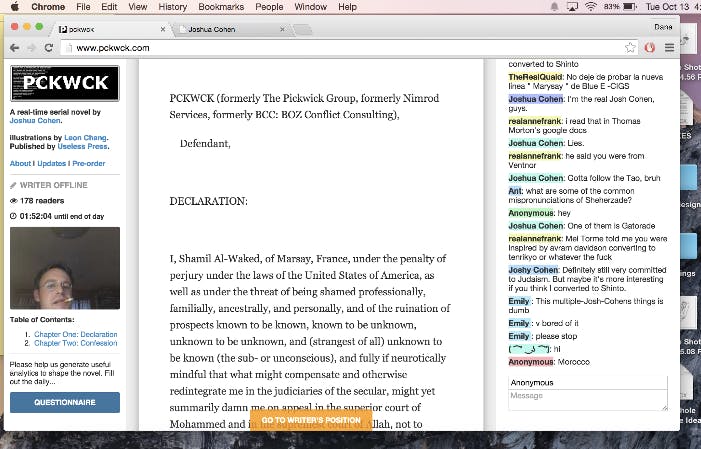

PCKWCK begins with a protagonist named Shamil Al-Waked in a legal face-off with corporate

entity called PCKWCK, but from there it twists into an often-meta narrative that seems content to disregard the

basic structure of narrative altogether.

Whereas Charles Dickens wrote for the everyday man—stories driven by plot and peppered with

comical, exaggerated characters—Cohen’s style is dense, almost impenetrable at times. Those

qualities are all the more emphasized by PCKWCK’s current home on the Internet, where

content tends to acquiesce to the preference for short, digestible, and easily scrollable.

The connection to Dickens, then, as Cohen noted, is a more contextual and thematic link than

anything that might resemble one-to-one modernization of his work or style.

“Serialization really came about in Dickens’ time of the Victorian era because of an enormous

explosion in mass printing. Paper’s cheaper, and you have the linotype machine that’s just

spitting out more and more copies of things—so that was the demand for increasingly productive

culture workers. So, technical shift leading art.”

If serialization was the literary tend that defined Dickens’s era, PCKWCK poses the

notion that our culture calls for a novel that can satisfy the voracity and impatience of the

Internet era, a novel written before our eyes with our daily consent. “Every culture gets the art it

deserves,” Cohen said. “And this is a culture that believes deeply in transparency, so I wanted

to do this transparently.”

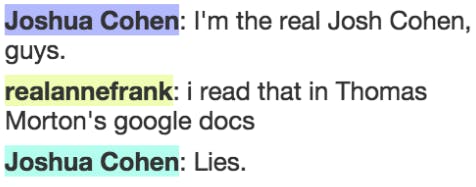

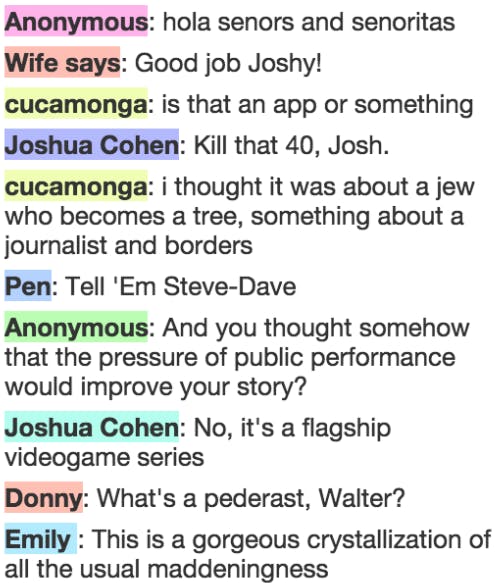

In addition to the continuously updating text and live feed of the author, PCKWCK.com allowed

readers to make comments anonymously in a sidebar, which Cohen would read every night,

alongside data from a questionnaire, to inform his writing the next day.

Cohen quoted some of the comments into the manuscript directly; he turned the anonymous

posters, the heckling chorus of humanity’s worst impulses, into the villains of the story.

“The commenters are sort of cast in the role of Pickwickians themselves. They’re the torturers.”

“The commenters are sort of cast in the role of Pickwickians themselves,” he explained. “They’re the torturers. I just knew if part of the project was that there were going to be open

anonymous comments, the only way I could implicate some idea of responsibility was to cast

them in a role that most people would find unacceptable.”

Useless Press will be publishing PCKWCK with pages that include user comments and

submitted data in addition to Cohen’s text, and illustrations by Leon Chang, with all of the

proceeds go the ACLU.

“It’s not going to be interesting to just read it,” Cohen said, meaning without considering the context that will be provided. PCKWCK as an entity is

inextricable from the process by which it was created. The novel—for lack of a better term—is

what emerges from the synthesis of all of the Internet elements that fed it.

For five days, five hours a day, Joshua Cohen was the literary David Blaine. He was

surviving in a glass box above a city, or freezing himself in ice for 64 hours, just to make a

statement about humanity. Or to show us that he could do it. Or to prove to himself he

could do it.

But there was no money at stake, no broadcast special, no

cameras aside from the single jerky webcam on his computer. For twenty-five hours, the Internet could watch Joshua Cohen write a novel in real time. And it may be too soon to say exactly what we

learned.

Photo via Remko van Dokkum/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)