If you’ve been anywhere near a computer in the past six months, you’ve probably noticed that HBO’s John Oliver seems to be accomplishing a great many superhuman feats.

When he’s not ripping apart the insane math of the Miss America contest, or destroying the myth of the American dream, he’s busy becoming one of the best journalists on TV — all with enough spare time time to win the Internet and go on epic, 13-minute rants that you simply have to see.

This effusive coverage is not especially new: Jon Stewart was joking about the slightly deranged headlines written about him years ago. But in today’s seizure-inducing online culture, where everything is dialed up to 11 all the time, Oliver has been canonized at record speed by the liberal-leaning Internet.

And it’s not just your tried-and-true aggregators writing breathlessly about everything Oliver does. Sure, Gawker and Buzzfeed staff get up on Monday morning and repackage like crazy; but Last Week Tonight’s skits are also traffic-fodder for those who profess to buck the quick-and-easy trend, like Vox (which featured Oliver on its homepage three times in one day last week), and the Wall Street Journal (which had two separate stories repackaging a single Oliver segment).

It’s all a lot for one man — so much so that Oliver has publicly protested (saying he’s too full of “self-loathing” to handle the praise). But here’s why it happens: because Oliver and his team deliberately produce a kind of media that is perfectly designed for right here, right now.

The way the Internet has evolved in the last few years has created a media economy geared heavily towards that dreaded word, content — all those video clips and repackaged stories and OMFG moments that make up a huge chunk of any modern site. It’s not news, exactly. But it’s not not news. It’s stuff.

For all of the great web-based journalism that attracts a slew of attention based on its own merits, the vast majority of material online is highly ephemeral, produced quickly, and needs to be heard above the din of the rest of the Web.

And that’s where Oliver comes in. He’s perfect for this environment. He’s super-smart and funny, and he focuses on topics that don’t get much attention in the daily media conversation. That means people feel good about sharing his work, and journalists don’t get that “is this really why I got into this field?” vibe when they write about it. Everybody wins — especially Oliver, whose YouTube account racks up millions of views.

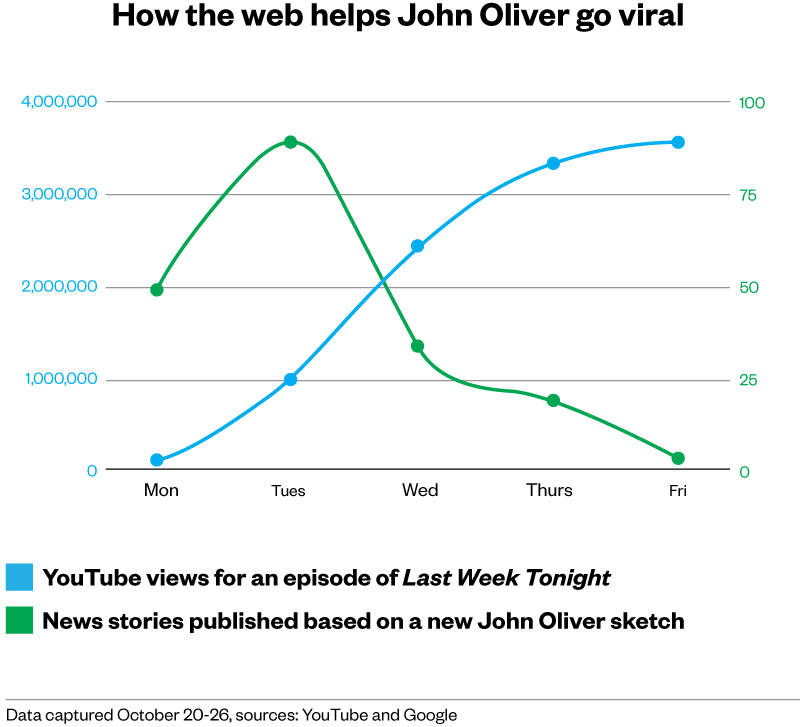

Take a look at how things spread once the show goes out on Sunday nights.

As someone who recently came off a long stint running the Huffington Post’s media section — is this the moment where I unmask myself as a member of Aggregators Anonymous? — I know all too well the dynamics that play into this pattern. (I’m not kidding: That headline about Oliver’s becoming one of the best journalists on TV was one I wrote.)

When you’ve got one eye on your traffic and another on your Facebook stats, you learn quickly to cherish those personalities and topics that can be counted on to reliably deliver the goods — whether, as in my old job, that means highlighting every stupid thing said on Fox News, or whether it means bowing down to Oliver every week with increasingly hyperbolic headlines.

As long as the Internet stays this way, the pattern is likely to remain the same, too. If that makes you depressed in any way, well, life is full of struggles and — oh, and hey! Did you see that new John Oliver video?

This piece originally appeared on Medium, and was reprinted with permission.

Photo via TechCrunch/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)