When it comes to racial issues, Jeb Bush is hiding his politics in plain sight.

For several weeks, there’s been inquiry about how the beloved former Florida governor and early frontrunner’s status as a moderate could distinguish him from his fellow presidential challengers on matters of race. But his recent statement on the ongoing #BlackLivesMatter protests, as well as his policy track record, show that Bush represents more of the same old racially coded rhetoric that’s been used by his predecessors to rally a conservative base.

As Gawker’s Jason Parham notes, Bush’s remarks this week on the campaign trail took a swipe at the young people who have kept the #BlackLivesMatter movement at the forefront of public dialogue on race and injustice in America. Speaking to an audience in South Carolina, the epicenter of both the Charleston attack and the Confederate flag debate, a participant asked Bush how he and the Republican Party would appeal to Democrat voters who solidly support teachers unions.

Bush’s answer drifted into a cautionary tale about a certain kind of young person who has no ambition, doesn’t have “mentoring and nurturing,” and how it wreaks havoc on communities. In doing so, he called out two predominantly black communities as examples (emphasis added):

Kids in this country are aimlessly wandering around in their lives because they’ve never been told they were capable of learning. They’ve never been challenged to achieve far better. They’ve never really had the kind of mentoring and nurturing that gives them the sense their lives could be better. You see what happens in Baltimore and Ferguson. You see the tragedies play out. You see people becoming so despondent they take actions that are horrific.

It’s quite the clever sleight of tongue. Without ever using the terms “urban,” “black,” or “African-American,” Bush found another way to conjure up these identifiers, using the mental shortcut of naming two distinct areas that have been the site of black struggle and resistance—namely, Ferguson and Baltimore.

It’s a value judgment in its purest form, one that suggests black people are getting in the way of their own educational attainment and achievement. Or, in other words, “they need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps” and change how they think about the value of education.

Rather than say any of this explicitly, however, Bush relied on the implicit meaning of words such as “being challenged to achieve far better,” “capability,” and “nurturing” as a nod to personal values extolled with fervor from conservatives—“hard work,” “independence,” and the notion of “family.”

These appeals to white conservatism aren’t anything new. Indeed, Bush’s response is another profile in “dog-whistle politics,” a form of political messaging that sends a resonant signal to an intended audience, typically with implicitly negative value judgments about another specific group. As University of California at Berkeley professor Ian Haney-Lopez describes it, politicians may use calculated word changes, often racially coded, in order to push policy measures that purportedly help everyone, but actually hurt communities of color.

In a January 2014 interview, Haney-Lopez told Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman: “Politics now is occurring in coded terms, like a dog whistle. On one level, we hear clearly there’s a sense of racial agitation; on another level, plausible deniability—people can insist nothing about race at all.”

During the 1980s, President Reagan described the welfare system as a “poverty trap” and a “system of dependency,” as he pushed for an overhaul of government benefits. But in doing so, Reagan introduced the “welfare queen” into the mainstream conversation as an example of alleged abuses—specifically, women who defrauded their way into collecting welfare checks and lived lavishly off taxpayer dollars. It was a racialized trope, indeed.

As Josh Levin wrote at Slate, “this image of grand and rampant welfare fraud allowed Reagan to sell voters on his cuts to public assistance spending.” He continues, “The ‘welfare queen’ became a convenient villain, a woman everyone could hate. She was a lazy black con artist, unashamed of cadging the money that honest folks worked so hard to earn.”

And during the 2012 Republican presidential primary, Newt Gingrich famously brought back these tropes of black poverty by referring to Obama as the “food stamp president.” Gingrich falsely claimed that “more people have been put on food stamps by Barack Obama than any president in American history.”

It was a statement called out by writer Walter Mosley in an op-ed for CNN, who argued that such rhetoric “brings up the working person’s fear, looming reality, and in some cases the actual experience, of unemployment—while making a shout-out to racism and affixing a stigma to poverty. All the while hiding behind the symbol of a flag.”

During another campaign speech, Gingrich even waxed poetic about how “urban” youth didn’t know the value of hard work, and needed to be taught through after-school jobs programs, where they could earn money in exchange for tasks such as “light janitorial duty.”

However, Gingrich and Reagan are far from the only examples—many of which cut across party lines. Perhaps the most famous is the time-honored appeal to “states’ rights,” which was used by Alabama governor George Wallace as a way to defend segregation and “talk about blacks without ever mentioning race.” As Haney-Lopez explains:

“States’ rights” was a paper-thin abstraction from the days before the Civil War when it had meant the right of Southern states to continue slavery. Then, as a rejoinder to the demand for integration, it meant the right of Southern states to continue laws mandating racial segregation—a system of debasement so thorough that it extended to churches and schools, to housing and jobs, to eating and drinking … to virtually all forms of public transportation, to sports and recreations, to hospitals, orphanages, prisons, and asylums, and ultimately to funeral homes, morgues, and cemeteries.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, Reagan and Clinton pushed “law and order” as a way to encourage the War on Drugs—which predominantly targeted low-level offenders in communities of color. And in 2014, Paul Ryan referred to a “culture problem” in “our inner cities in particular,” relying on the implicit connection to “ghettos” in order to blame inner-city residents for their own poverty.

And Bush’s remarks likewise point the finger at youth of color and generations of parents living within impoverished communities that continue suffering from overpolicing and racial disparities in education. Many black young people in urban areas like Ferguson and Baltimore work with what little resources are invested into their community, particularly in employment opportunity and school funding.

And many of them work, against all odds, to support themselves or their families, in hopes of creating a better life one day. These same urban areas scare some Americans so much that a smartphone app was created to determine which neighborhoods are “sketchy” and not worth visiting or patronizing with business. These communities are often deemed beyond repair, disposable, and, thus, lacking in value.

It’s a value judgment in its purest form, one that suggests black people are getting in the way of their own educational attainment and achievement.

In shifting the focus from education to black community values, Bush didn’t acknowledge that issues of disparity underscore the passions of young people protesting in major urban centers. In the process, he gave a potential voting base a reason not to feel guilty for their apathy or disgust for the protesters. Believe it or not, black young people want and desire better; they just don’t live in a country that’s structured and operated on the belief that they deserve better.

Like Reagan before him, Bush’s word choice speaks to a social policy that at odds with the welfare of black Americas. For example, Bush touts his elimination of affirmative action in Florida’s public colleges and universities as a boon for increasing black and Hispanic enrollment.

As Politifact reports, Bush trumpeted the move while speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Feburary: “I eliminated affirmative action by executive order—trust me, there were a lot of people upset about this. But through hard work we ended up having a system where there were more African American and Hispanic kids attending our university system than prior to the system that was discriminatory.”

But the sleuths at Politifact rated the claim “mostly false,” citing the decreased percentage of black students in Florida state schools since Bush’s 1999 executive order as Florida governor.

“The number of Hispanic students has gone up considerably, but that is partly because of a recent change in how students report ethnicity during the admissions process,” Politifact concluded. “There’s no hard evidence Bush’s One Florida program had much to do with the enrollment changes. Experts say demographics, graduation rates and state-sponsored scholarship money have had more influence.”

In other words, a program that’s intended to help level out disparities in educational attainment was axed by Bush, attacked as “reverse discrimination,” and then positioned as a win, not a loss, for communities of color.

If Bush truly cares about the educational attainment and life achievements of black young people, and why some of them struggle to “achieve better” in life, maybe he’d be better off actually listening to the young people he’s judging. He can test the limits of his own understanding, beyond racial tropes and surface-level value judgments—implicit biases that often make their way into how public policy is written and enforced.

Derrick Clifton is the Deputy Opinion Editor for the Daily Dot and a New York-based journalist and speaker, primarily covering issues of identity, culture and social justice.

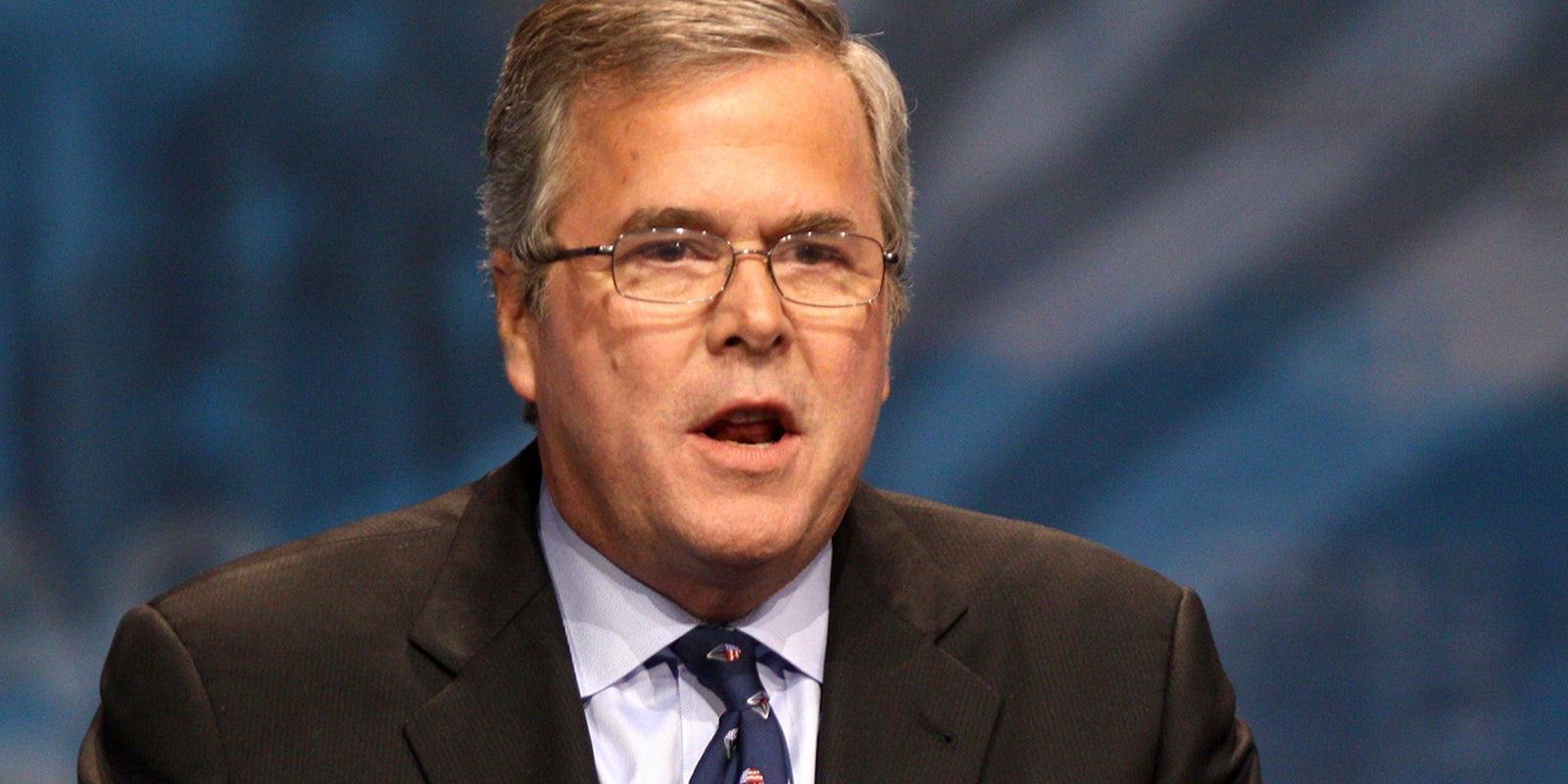

Photo via Gage Skidmore/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)