On Monday, Google released the iPad and iPhone versions of its augmented reality game Ingress. The game, developed by Google’s so-called internal startup Niantic Labs, has been around on Android for almost two years and has accumulated over four million downloads, according to TechCrunch. But its launch into the App Store opens up a whole new market.

The premise of the game is relatively simple. Alien mind-control data is leaking into our world through portals. Players choose a side, the Resistance or the Enlightenment, and work to gain control these portals. It’s basically augmented-reality capture-the-flag—or Foursquare, but with a point.

John Hanke, Niantic’s Vice President, describes the game as an “entertainment enabler.”

“The game itself is the motivation,” he told the Guardian. “But it’s the social interaction and exploration that the game encourages that are the real payoffs. People who meet up with other players and go on adventures together have the most fun and therefore tend to be some of the most dedicated and enthusiastic participants.”

“To be a great Ingress player,” reads the New York Times’ review of the game, “you need to have an enormous amount of time on your hands, or—and this is what Google wants—you need to collaborate with others, who can be found by using the app as well as by joining local communities of Ingress ‘agents’ organized on the social network Google Plus.”

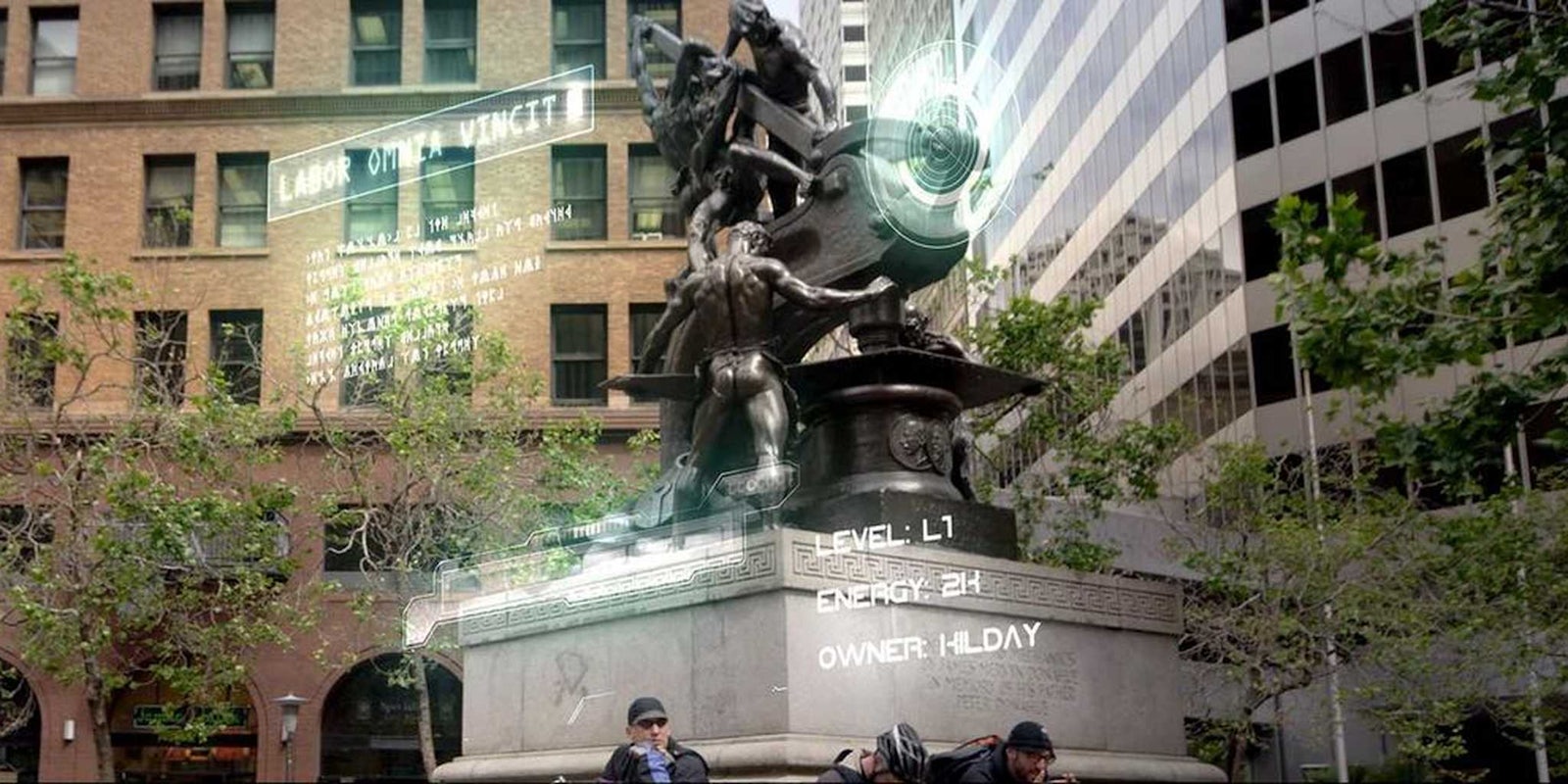

Screenshot of the desktop app

Players walk around, and when they are within a certain distance of a portal—usually some kind of monument or landmark—they can interact with it (e.g. take control of it, set up defenses). Players collaborate with each other to establish connections between portals. Because you cannot establish a connection between two points if the line between those points will intersect with an already existing line belonging to the other team, players try to take over larger swathes of territory in one fell swoop by establishing control of several points at once, creating a polygon shape on the map.

As that gameplay description might have revealed, the mechanics of the game are not—at least for me—very intuitive, and I feel cramped using the app on my iPhone. There’s just too much going on. And so much work, just to be out in the world. As mediated as our experience with the physical world is by mobile technology, there’s something a little bit creepy about turning it into a game. And one built around the all-seeing, all-knowing Google at that.

“The looming ‘Internet of Things’ is supposed to link all our objects — our cars, our refrigerators, our books, our shoes — into a seamless network that improves our lives,” the Times’ review concludes. “Ingress points to a less prosaic vision for such a world, one where ordinary-seeming places and objects are dense with fiction.”

This is certainly true, and still seems overwrought. It is strange to imply that our world, our “ordinary-seeming places and objects” are not already dense with fiction, or at least with true stories that become fictionalized over time.

“Think of a world in which you have thousands of stories layered on top of the places you visit,” Henke tells the Times. Do you really have to think so hard? To me this seems like as good a description of our world, free of augmented reality games, as any: We are inheriting, making, and imposing meaning—through stories—all of the time.

Maybe it is an arbitrary and needless distinction to insist that one kind of story-telling is more valuable or authentic than another—usually such distinctions are. But to imagine that Ingress points to a future where the narratives of our daily lives are something transmitted to us through our smartphones is nevertheless unsettling.

Of course, that is already happening—it just takes a game like this to make it obvious.

H/T Betabeat | Image via Ingress