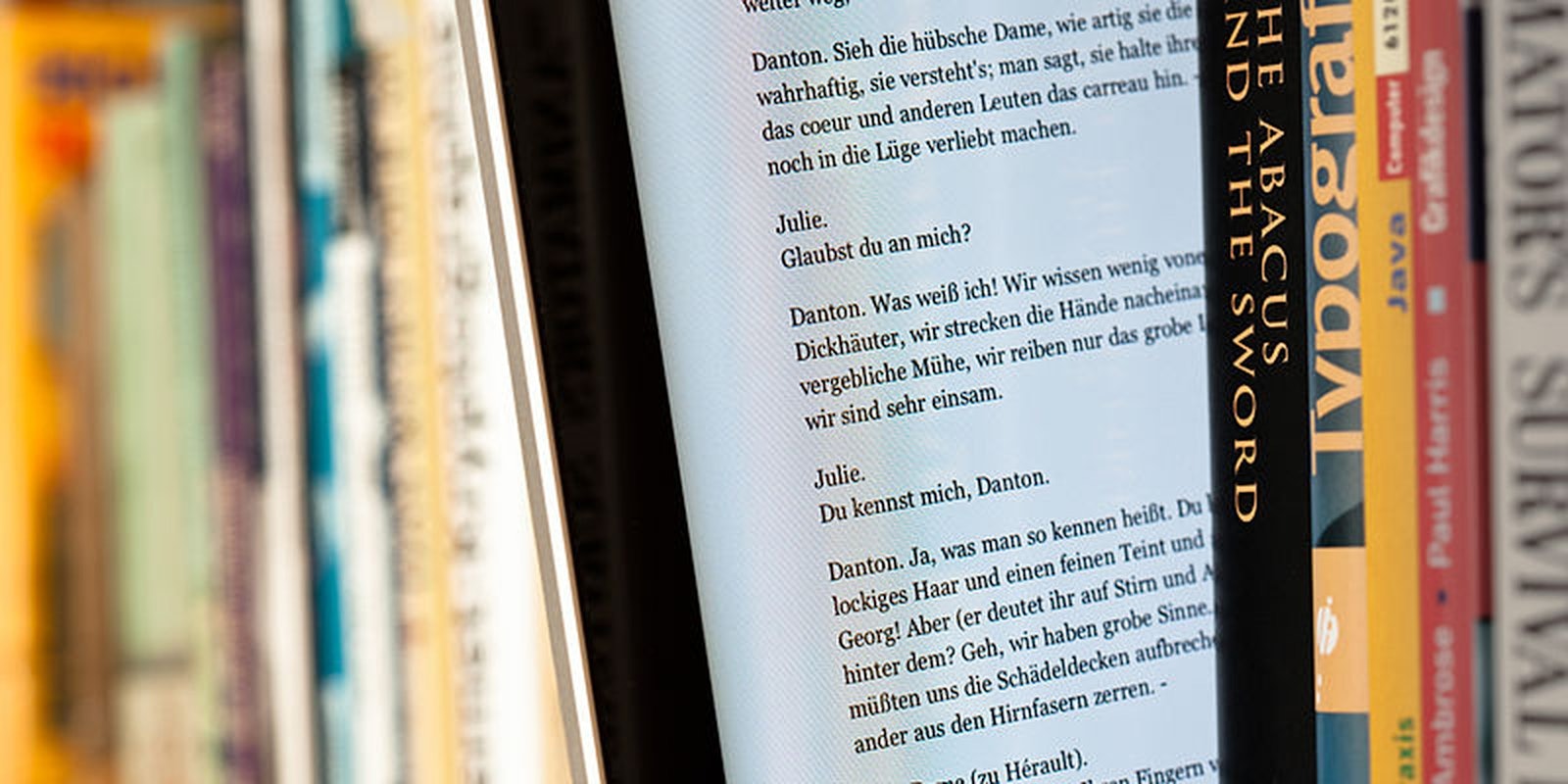

If there’s one important lesson to be taken from the battle between ebooks and traditional print, it’s that sometimes there are no winners and losers, just a delicate seesaw act.

This week, that seesaw tipped a little bit towards the argument for print, when a study was released in which 50 people were all given the same Elizabeth George story to read. The outcome indicated that readers retain more when engrossed in a traditional book than they do when looking at something on a Kindle. Reporting the findings for The Guardian, Alison Flood quoted Anne Mangen, a lead researcher on the study from Norway’s Stavanger University, who said that “the haptic and tactile feedback of a Kindle does not provide the same support for mental reconstruction of a story as a print pocket book does.” She continues from there:

When you read on paper you can sense with your fingers a pile of pages on the left growing, and shrinking on the right… You have the tactile sense of progress, in addition to the visual … [The differences for Kindle readers] might have something to do with the fact that the fixity of a text on paper, and this very gradual unfolding of paper as you progress through a story, is some kind of sensory offload, supporting the visual sense of progress when you’re reading. Perhaps this somehow aids the reader, providing more fixity and solidity to the reader’s sense of unfolding and progress of the text, and hence the story.

This Elizabeth George study confirms what many have long suspected, which is that ebooks are and always will be inferior to print, and that they can be detrimental to the essentialness of immersing oneself in literature.

That said, while the struggle between ebooks and print has already claimed several victims (e.g. book stores), the fight is less one-sided than you might think. The majority of projections have ebooks surpassing print books sometime in the next few years, and yet at the moment, things aren’t as dire for print as traditionalists tend to make them out to be. In April, Jim Milliot of Publishers Weekly inspected the numbers on either side and found that both the rise of digital sales and the decline of print sales have slowed. So for now, print lovers can rest their weary heads in the knowledge that although ebooks are popular, they’re not completely pervasive.

The possibility that usually gets obscured in this debate, meanwhile, is that ebooks aren’t necessarily supposed to be the same as print. In defending printed books for Mashable, editorial director Josh Catone admits that as he sees it, “Ebooks are not simply a better format replacing an inferior one; they offer a wholly different experience.”

Ebook fans cite their emerging potential in this regard to open up possibilities where traditional media can’t. Allen Weiner at The Daily Dot, for one, argues, “Ebooks have created greater democratization in the creation and distribution of new literature and event scholarly thinking. Without having to go through the iron gates of major publishers, new authors have emerged who have access to an unprecedented number of digital self-publishing platforms.”

But what about the act of reading an ebook instead of a printed book? What is it about that experience that’s worthwhile, especially if, as the recent Elizabeth George experiment suggests, e-books have less impact in the long-term?

According to a Pew Internet study from 2012, consumers enjoy ebooks for their ability to offer a wide selection, for their fast delivery, and for their easiness to read while traveling. What this basically says is that ebooks are great for when you’re on the go; they give you the books you want, they give them to you fast, and they allow you to take those books with you no matter where you are.

In the case of Amazon, there are plenty of titles that Kindle products don’t provide, but the reality is that Amazon does posses more than enough titles to make a Kindle appealing to someone that wants options. And certainly, being able to download something with the touch of a button, rather than waiting for shipping, or going out to buy it, holds appear for any busy person. Moreover, if you’re going on a trip, or just making your daily commute on the train, it’s a lot easier to choose from options on your tablet than it is to carry a bag full of books around.

Based on this analysis, it would be easy to assume that the majority of ebook users are young, tech-savvy professionals, looking to stay well-read, without taking any extra time out of their busy schedules.

But this isn’t entirely accurate. Newer Pew Research statistics put the lion’s share of e-readers between the ages of 30 and 64. However, tablet owners are a little younger, generally somewhere under age 50.

In conjunction with this, a CNET poll from 2009 put 50 percent of Kindle users specifically over 50 years old. Bloomberg Businessweek’s Bruce Nussbaum observed this in action the same year. “Every time I see a Kindle, it is held by a Boomer,” Nussbaum declared.

Amazon’s Kindle products are known for being the most popular options for ebooks overall, with their the Kindle e-reader leading the charge, the Apple iPad in second place, and the Kindle Fire in third. So if logic follows, older people are actually embracing ebooks more than anyone, while people on the younger end of the spectrum are using tablets in particular when they want to read in non-print form. This implies that, contrary to popular belief, older readers are embracing new technology when it comes to books, rather than refusing to stray away from print altogether.

Even more interesting is Pew’s conclusion that 87 percent of ebook readers read a print book in the last year, too, and 35 percent of print book readers also read an ebook. Assuming this is accurate, print readers are more steadfast on the whole, but, given the amount of overlap on both ends, neither side is completely against the other. Or, to put it another way, people who like to read just like to read. Regardless of changes in the how they do that, those that love books will come back for them again and again no matter what the method is.

This is undoubtedly because of the simple truth mentioned before, which is that smart and voracious readers recognize ebooks and traditional print for their distinctive benefits. Ebooks work great for when you’re busy, but there’s an unmistakable intimacy to print. The same study which detailed why people like ebooks also detailed why people like print books, the chief reasons being that they’re better for reading to children and for sharing with others.

In 2014, people buy print books largely because of their physical presence. It’s similar to streaming a movie versus buying a DVD/blu-ray. Streaming is easier in most cases, but if you buy a physical copy of a movie, it’s uniquely yours. You can put it on the shelf, and even if you don’t decide to watch it, its tangible existence is a reminder of how much it means to you. And chances are it means something, otherwise you probably would’ve just tried to steam it.

Elizabeth George herself told The Guardian, “I’m thinking it might make a difference if a novel is a page-turner or light read, when you don’t necessarily have to pay attention to every word, compared to a 500-page, more complex literary novel, something like Ulysses, which is challenging reading that really requires sustained focus.”

The moral of the story here is to put the E.L. James on your Kindle (if you’re not too embarrassed to read her in public) and save the Donna Tartt for print. At their best, e-books are kind of like Netflix. They’re fast, they’re cheap, and you they’re something you can enjoy almost anywhere. But if you’ve truly loved a book (or a movie) at some point in your lifetime, you know that going digital doesn’t always cut it.

Photo via melenita/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)