Whenever February rolls around, I always find myself engaged in a conversation with fellow African Americans about some moment during our lives where we were intentionally or unintentionally made to feel uncomfortable about the existence of Black History Month. We all have stories of a teacher, classmate or friend who expects you to create a presentation or educate the masses about black existence. And despite people for the most part having the best intentions, something has always felt inherently wrong about this request or expectation.

And of course there are always people who argue about the supposed unfairness in the existence of this month-long reflection because white history does not have its own designated month. In the face of this repeated objection, we, for the most part, have to simply focus on making these 28, sometimes 29, days as productive as possible.

Essentially, the month is always one part joyful reflection upon black life. Unfortunately, the other part is acknowledging the frustrating realization that uncomfortable encounters are unavoidable and that black people will almost constantly be required to justify the need for setting aside time for educating people about black history.

In recent years, I have noticed how the digitization of history, especially African-American history, has reshaped the conversation and removed some of the unavoidable tension.

For black Americans the month is more than an acknowledgement of our past, but also a constructive and progressive act of social defiance with the goal of bettering American society. And in recent years, I have noticed how the digitization of history, especially African-American history, has reshaped the conversation and removed some of the unavoidable tension.

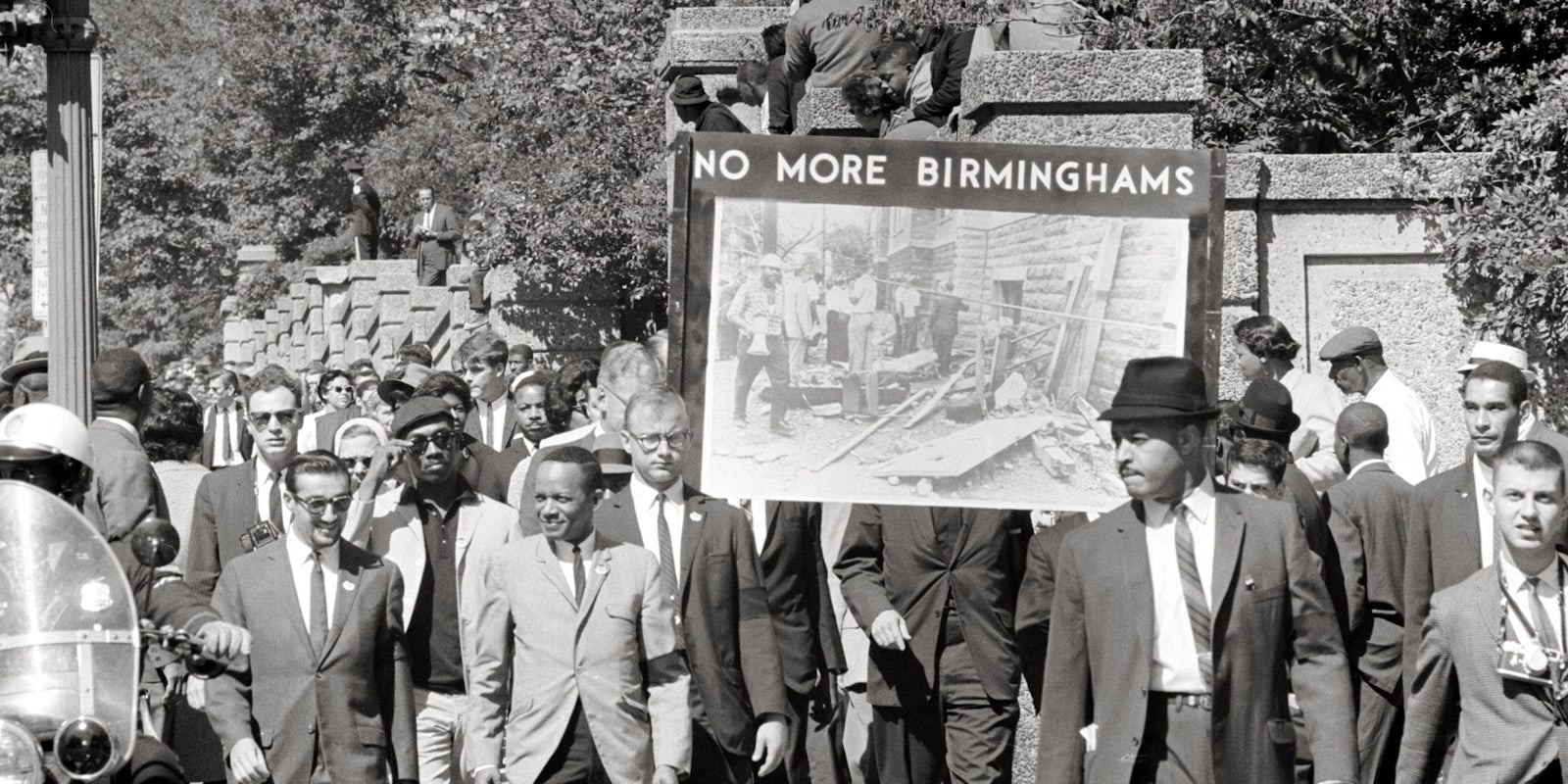

For example, the New York Times has decided to commemorate Black History Month with a new section called “Unpublished Black History,” where they will feature unpublished photos from their archives depicting “revealing moments in black history.”

During this month, they will continue to add new stories and photos every day to further the discussion. By doing so, they are not only acknowledging that there are stories and experiences unique to black life that are worth sharing, but most significantly, they are confirming that for long stretches of American life these vital stories and images in some cases were deemed unworthy of publication.

Case in point is this photo and accompanying article, “The House Bars Adam Clayton Powell Jr.”

It describes how in 1967 the House of Representatives prevented African American Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. from taking his seat because as one supporter described, “He was just too powerful for a Negro.” Eventually, Powell was forced to take his case to the Supreme Court, so that he could reclaim his seat, and in 1969 he prevailed in Powell v. McCormack.

Stories such as this are ones that most Americans, regardless of race, are probably not familiar with. And honestly, we would all prefer to imagine that we live in a society that would not tolerate this bigotry, but the re-emergence of lost history forces all of us to reimagine and reassess our understanding of the past.

It becomes easier to understand how traumatic this environment must have been for an African American considering that danger, financial hardship and terror in the form of church bombings, loss of employment, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., beatings at the hands of the police, and more regularly befell these Americans during the 1960s merely because they wanted to vote and get closer to this American Dream thing that they had heard about, but were never encouraged to obtain.

We would all prefer to imagine that we live in a society that would not tolerate this bigotry, but the re-emergence of lost history forces all of us to reimagine and reassess our understanding of the past.

The injustices that Powell faced merely for aspiring to be a good public servant could have been lost to the ages if the New York Times’ photos and reporting were not removed from the archives, digitized and added to the infinite repository that is the Internet.

“We didn’t run photos back then the way we do today,” Times photo editor Darcy Eveleigh told Nieman Lab.

“This was a way to explore not just the stories we publish but also the process, and how things are published and when things aren’t, what gets left on the cutting room floor,” Times Deputy Digital Editor Damian Cave said.

Due to the ubiquity, comfort and dependence we all have with the World Wide Web, the simple act of digitizing archived photos and placing them on the Internet can seem trivial—but for a people who annually have to justify the need for discussing their history, this simple act changes the entire equation.

The equation shifts because history for the most part has always been a siloed narrative retold generation after generation by the victors. In the American context, African Americans have not been the victors in our society, so there is an inherent difficulty in telling our stories to the masses. Black History Month has only been officially recognized by American presidents since 1976. Our narrative undermines components of the victorious, ascending American narrative.

However, one’s understanding of history changes when the discussion is no longer siloed, myopic and skewed towards the powerful, and instead is constantly interwoven with little concern for ascending or descending societal narratives. The Internet allows for this remapping and grander understanding of history, and as a result the opportunity to humanely, and accurately retell the lives of oppressed people emerges.

The image of Powell standing behind the railing, unable to take his seat and serve on behalf of the American people, while a large gang of white congressmen ignore his presence and are entirely content with disenfranchising and oppressing an American because of the color of his skin, allows all Americans to see with greater clarity the bluntness and inhumanity of much America’s race relations.

It is hard to determine what has prompted the New York Times, other publications, and countless Americans to want to revisit a history that we know are full of unpleasantries and injustices. Maybe it was the election of President Barack Obama. Maybe it is the greater integration in education, housing, and the work force, and the increase in interracial families that has made Americans more comfortable with confronting an American history and existence that was forcefully oppressed and intentionally ignored.

Maybe it’s because, through the Internet, we are more able to share our past with people across the globe.

Who knows what brought about this change, but the more ubiquitous and interwoven African American history becomes within the narrative of American existence, the greater our society will be become.

Barrett Holmes Pitner is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist and columnist who focuses mostly on race, culture, and politics, but also loves to dabble in sports, entertainment and business. His work has appeared in The Daily Beast, Huffington Post, National Journal, the Institute for War & Peace Reporting and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter @BarrettPitner.

Image via U.S. Library of Congress / Wikipedia