Warning: This contains spoilers for the series premiere of House of the Dragon.

For all of its spectacle and character moments that made it a phenomenon, Game of Thrones thrived in the unraveling of lore and prophecy. And while much of House of the Dragon will be a very different show, it’s at least continuing the tradition of prophecy with a whopper of a declaration that connects HBO’s two series together—but also fundamentally changes how we view one aspect of George R.R. Martin’s seminal series.

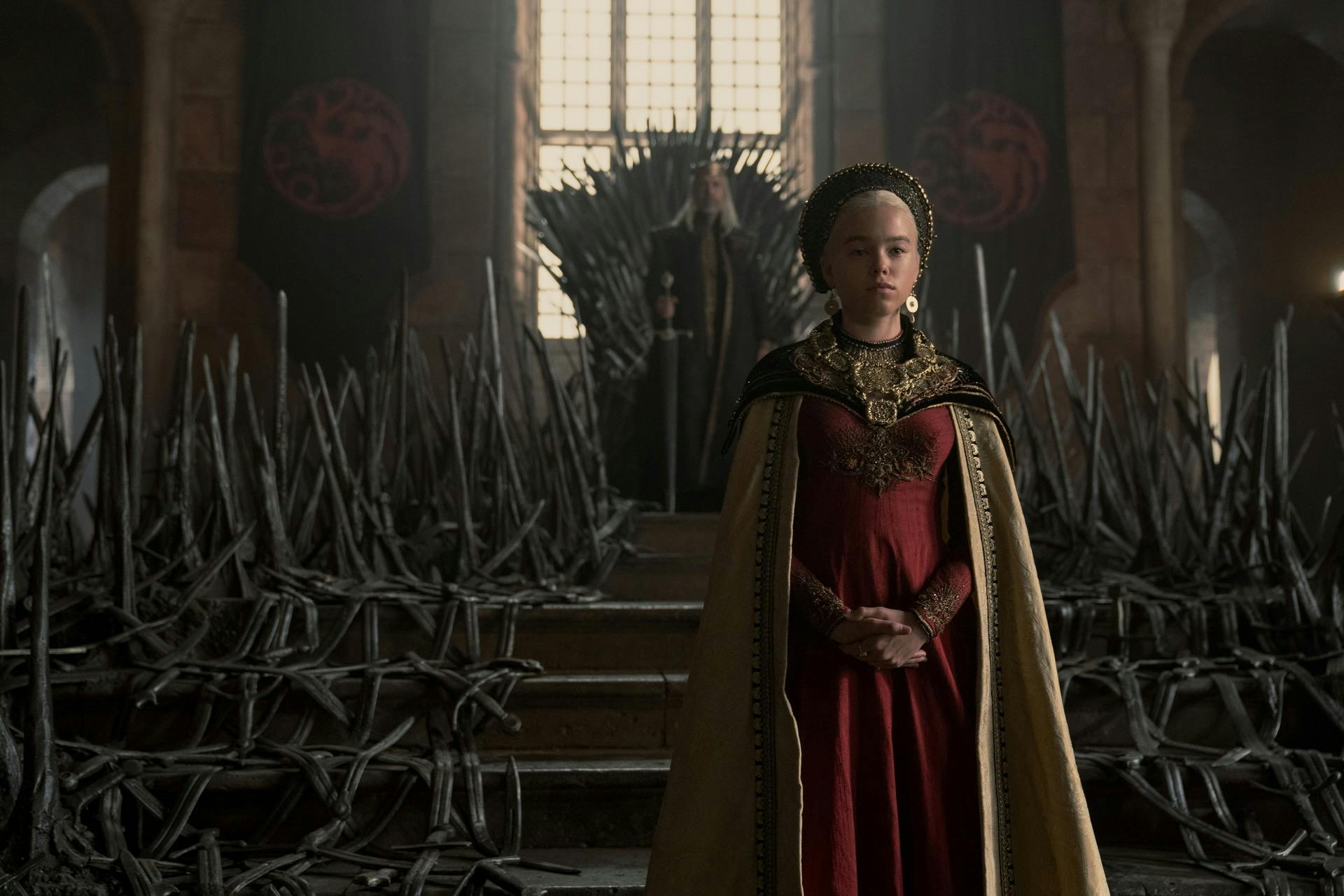

At the end of the series premiere, “The Heirs of the Dragon,” King Viserys I Targaryen (Paddy Considine) brings his daughter Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock) into the depths of the Red Keep where the skull of Viserys’ dragon, Balerion the Black Dread, is kept; candles lit everywhere give off the air of a tomb and a place to pay one’s respect to the dragon whose first rider helped conquer Westeros. You know, the perfect place to hold a very important and weighted conversation.

The reason Viserys brought Rhaenyra down to Balerion’s memorial is twofold. He’s bypassing the male precedent of Targaryen succession to make Rhaenyra his heir over Daemon (Matt Smith), Viserys’ hotheaded younger brother. Viserys’ small council already didn’t trust Daemon, with the hand of the king Otto Hightower (Rhys Ifans) noting that if Daemon sat on the Iron Throne he would become a second Maegor (a particularly cruel and ruthless Targaryen king), and that’d be a worse fate than bypassing “tradition and precedent” to name Rhaenyra his heir. For most of the episode, Viserys resists because, as much trouble that Daemon causes, Viserys loves his brother.

But the real catalyst lies in a personal insult that eventually reaches Viserys’ ears: While out with his Gold Cloaks, Daemon drunkenly toasted Baelon—Viserys’ son who died shortly after his birth, which his wife Aemma (Sian Brooke) did not survive—as the “Heir For a Day,” nodding to the brief period in which Daemon moved a spot lower in the order of succession.

Viserys apologizes to his daughter for overlooking her for so long, but his gift comes with a warning: The Iron Throne is the most dangerous seat in the world (and not just because of how the throne’s swords are harming the man who currently sits in it). But Viserys’ blessing also comes with the curse of knowledge, one that’s been passed down from ruler to ruler all the way back to the first Targaryen king, Aegon the Conquerer.

‘The Song of Ice and Fire‘

As House of the Dragon cuts between Balerion’s resting place and the upcoming ceremony in which the lords of every great house of Westeros—including some very familiar names—swear their loyalty to Rhaenyra as heir to the Iron Throne, Viserys begins to paint a very familiar picture for Rhaenyra, even if none of it will make sense to her right now.

“Our histories, they tell us that Aegon looked across the Blackwater from Dragonstone, saw a rich land ripe for the capital, but ambition alone is not what drove him to conquest,” Viserys explained. “It was a dream. And just as Daenys foresaw the end of Valyria, Aegon foresaw the end of the world of men.”

He’s referring to Daenys the Dreamer, a Targaryen who, nearly a century before Aegon the Conquerer’s birth, had a prophetic dream foretelling Valyria’s destruction by fire. Although the dream didn’t say when this destruction would occur, Daenys’ family took her dream at its word and transplanted themselves and five dragons and settled on Dragonstone. But they didn’t have to wait long, relatively speaking, for Daenys’ dream to play out: The Doom of Valyria, a mysterious “cataclysm” that wiped out the entire Valyrian Freehold, its citizens, and all of those dragons, arrived just 12 years later.

So when Aegon, Daenys’ great-great-great-grandson, had a dream about the importance of Westeros united under one banner (and under Targaryen rule) to save the realm from an unknown threat, Aegon, too, listened.

“It is to begin with a difficult winter, gusting out of the distant north,” Viserys continued. “Aegon saw absolute darkness riding on those winds, and whatever dwells within will destroy the world of the living. When this great war comes, Rhaenyra, all of Westeros must stand against it. And if the world of men is to survive, a Targaryen must be seated on the Iron Throne. A king or queen strong enough to unite the realm against the cold and the dark. Aegon called his dream ‘The Song of Ice and Fire.’”

We already know when this dream comes to pass: It’s in Game of Thrones

Anyone who’s seen Game of Thrones knows of what Aegon’s dream speaks: Nearly 200 years after “The Heirs of the Dragon” takes place, we see his dream play out as the Night King and his army of the dead attempt to overtake Winterfell before a united front of several Westerosi houses, Free Folk, Dothraki horselords and Unsullied soldiers, and a red priestess. Leading that united front was the last two Targaryens: Daenerys (Emilia Clarke), the exiled Targaryen princess who’d long staked her claim on the Iron Throne, and Jon Snow (Kit Harington), who was anointed King in the North by his own men.

Technically, neither of them is seated on the Iron Throne during the Battle of Winterfell—Cersei Lannister is the one who sat on the Iron Throne—but that’s probably more a matter of semantics than anything; in the eyes of the Targaryens, they’re the rightful rulers. But pretty much everything else comes to pass. The Night King is even killed with the same catspaw dagger made of Valyrian steel that Viserys keeps on his side, although Arya Stark’s the one who gets that final kill. Viserys might not know when the prophecy will play out, but as we see in Game of Thrones, it does play out. (The Night King, as a character, is a show invention and doesn’t exist in Martin’s books, but the dream could be in reference to the White Walker threat as a whole.)

If House of the Dragon’s predecessor didn’t immediately come to mind, House of the Dragon made the connection even more explicit: After Viserys says “gusting out of the distant north,” the camera cuts right to Lord Rickon Stark of Winterfell, the main ruler in the northern-most part of Westeros below the Wall, pledging his loyalty to Rhaenyra.

And, to harken back to another infamous promise, Viserys ends the discussion about Aegon’s dream (and a major exposition dump for the show) the same way that Lyanna Stark did on her deathbed after revealing to her brother Ned that her son was a legitimate Targaryen and asked Ned to protect him.

“This secret has been passed from king to heir since Aegon’s time, and now you must promise to carry it and protect it,” Viserys said. “Promise me this, Rhaenyra. Promise me.”

The other song of ice and fire

The other noteworthy phrase Viserys uses in telling Rhaenyra about Aegon’s dream is that Aegon called it “the song of ice and fire.” It’s significant both because A Song of Ice and Fire is the name of the fantasy series Game of Thrones is based on, but also because of the one instance that the phrase “song of ice and fire” actually showed up in ASOIAF.

That happens a little over two-thirds of the way through A Clash of Kings, the second book in ASOIAF, as Dany goes through the House of the Undying. Game of Thrones simplified this trip in the season 2 finale with a vision of the Iron Throne covered in snow and a brief reunion with Khal Drogo (Jason Momoa) and their son, but in ACOK, Dany sees several visions.

One of those visions involves her older brother Rhaegar—who Dany never met and doesn’t figure out his identity until a bit later—and his wife Elia Martell following the birth of their son Aegon. Rhaegar was famously something of a musician, so upon naming Aegon, Elia asked her husband if he would write a song for baby Aegon.

“He has a song,” the man replied. “He is the prince that was promised, and his is the song of ice and fire” He looked up when he said it and his eyes met Dany’s, and it seemed as if he saw her standing there beyond the door. “There he must be one more,” he said, though whether he was speaking to her or the woman in the bed she could not say. “The dragon has three heads.”

Dany later asked the warlocks about it and didn’t get any answers, and Jorah didn’t know what Rhaegar meant, either.

The Prince That Was Promised is a prophecy transcending both Westeros and various religions. Although the prince’s identity (prince being a gender-neutral term in Valyrian) in Game of Thrones was a tossup between Jon and Dany for much of the show, the series finale revealed that the prophetic prince, in the end, was Jon Snow. Aegon’s dream isn’t so much a revelation of new information, but a revelation that what we know has been around far longer than people ever knew.

How did Aegon’s prophecy get lost to time? And why haven’t we heard of it until now?

In Fire & Blood, the Targaryen civil war that will eventually come to pass on House of the Dragon and the decades of setup are largely based on the writings and testimonies of three individuals: An archmaester, a septon, and a fool named Mushroom. Each of them has its own agenda and its own purview, and oftentimes, those accounts contradict each other. But much of the conversations that transpired between the various Targaryens, Velaryons, Hightowers, and the other families caught up in the Dance of the Dragons is unknown. That’s where House of the Dragon comes in as it gives us a view of the conversation where Viserys placed a major weight on Rhaenyra’s shoulders, a conversation that none of the parties would’ve ever been privy to. (It’s unclear if Viserys ever told Daemon, his former heir, about this dream to prepare him for his turn on the throne.)

There are a few possible reasons why the dream might have been lost. You can point to the potential chaos that awaits these characters in the Dance of the Dragons. It’s possible that, if knowledge of the dream survives the Dance, future Targaryen kings eventually don’t put as much weight on the accuracy of the dream given no part of it played out in any way before their respective reigns.

And even if that knowledge made its way from Targaryen king to Targaryen king over the next 172 years to the year of Dany’s birth, it would’ve likely been lost when Jaime Lannister killed King Aerys II Targaryen to save King’s Landing from death by wildfire and Robert Baratheon killed Rhaegar Targaryen in a duel. Dany, who would’ve been a newborn at the time, could hardly have known about it. And Jon was a baby, too.

The real-world one is a lot simpler: It’s something that Martin has been planning for some time (more below) but he just hasn’t been able to include it in any previous text. It’s more or less the prophecy version of “we don’t see this new prequel character in the older show because they didn’t exist yet when the older show was being made.”

Is House of the Dragon revealing things from future ASOIAF books?

Martin and Ryan Condal, the creators of House of the Dragon, have both said as much. In an interview with Vanity Fair that took place shortly after the show’s world premiere last month, Condal noted that some “said I committed A Song of Ice and Fire heresy, but I did tell them: ‘That came from George.’ I reassured everybody.”

But Martin also offered his own explanation and added that “I’m still two books away from the ending, so I haven’t fully explained it all yet.”

“I don’t want to give too much away, because some of this is going to be in the later books, but this is 200 years before the events of Game of Thrones,” Martin told Vanity Fair. “There was no sell-by date on that prophecy. That’s the issue. The Targaryens that know about it are all thinking, Okay, this is going to happen in my lifetime, I have to be prepared! Or, It’s going to happen in my son’s lifetime. Nobody said it’s going to happen 200 years from now. If the Dance of the Dragons had not happened, what would’ve happened to the next generation? What would’ve happened in the generation after that? Yeah, there’s a lot to be unwound there.”

Aegon’s dream isn’t so much a revelation of new information, but a revelation that what we know has been around far longer than people ever knew. And, given the hints of what we might know about what’s to come, it makes us wonder what could’ve been had Westeros had the time to prepare for the threat that would one day arrive on their doorsteps.