By DARYL GREEN

Rare book librarians, renowned for their tweediness and navel-gazing, have been quietly doing a pretty good job keeping up with the digital revolution. We’ve been putting our treasures up on the Web with hi-res images and professional commentary; we’ve been opening access to our collections through catalogs and blogs; and we’ve focused on utilizing new technology to improve communication and service provision.

But how can a profession that is defined by collecting and talking old books stay relevant in the digital age? What will a “rare book” look like in 50 years? 200 years? How can we be certain that the documentary heritage of the age that we are living in now is preserved for future generations?

The book as a concept has remained essentially the same for thousands of years—but it also has retained this magic ability to be adapted and reformed to fit the age in which it has been created. Not only is the handwriting or the printing ink completely different, but the tools used to navigate a text (indexes, contents, running titles), the methods of illustration (hand-drawn, engraved, photographed) and the physical makeup of a book (its binding and paper) vary wildly depending on the era in which they were produced. A handwritten manuscript from the 11th century is instantly discernible when compared to a book printed in the 19th century. We collect these items from all different periods because they tell us about who people were, what they were interested in, and, perhaps most importantly, how they were conveying ideas and information to other people.

The idea of a “rare book” or a rare books collection is actually an invention of the late 19th and early 20th century. Before that, institutional collections maintained what was called a “treasure room,” where librarians hoarded all of the choice old books and private collectors knew what seller to turn to if they were after something of a difficult vintage. Antiquarian booksellers have their roots only in the late 19th century. In fact, the very concept of the age of the book as increasing its value—creating a higher price tag—is also relatively modern concept.

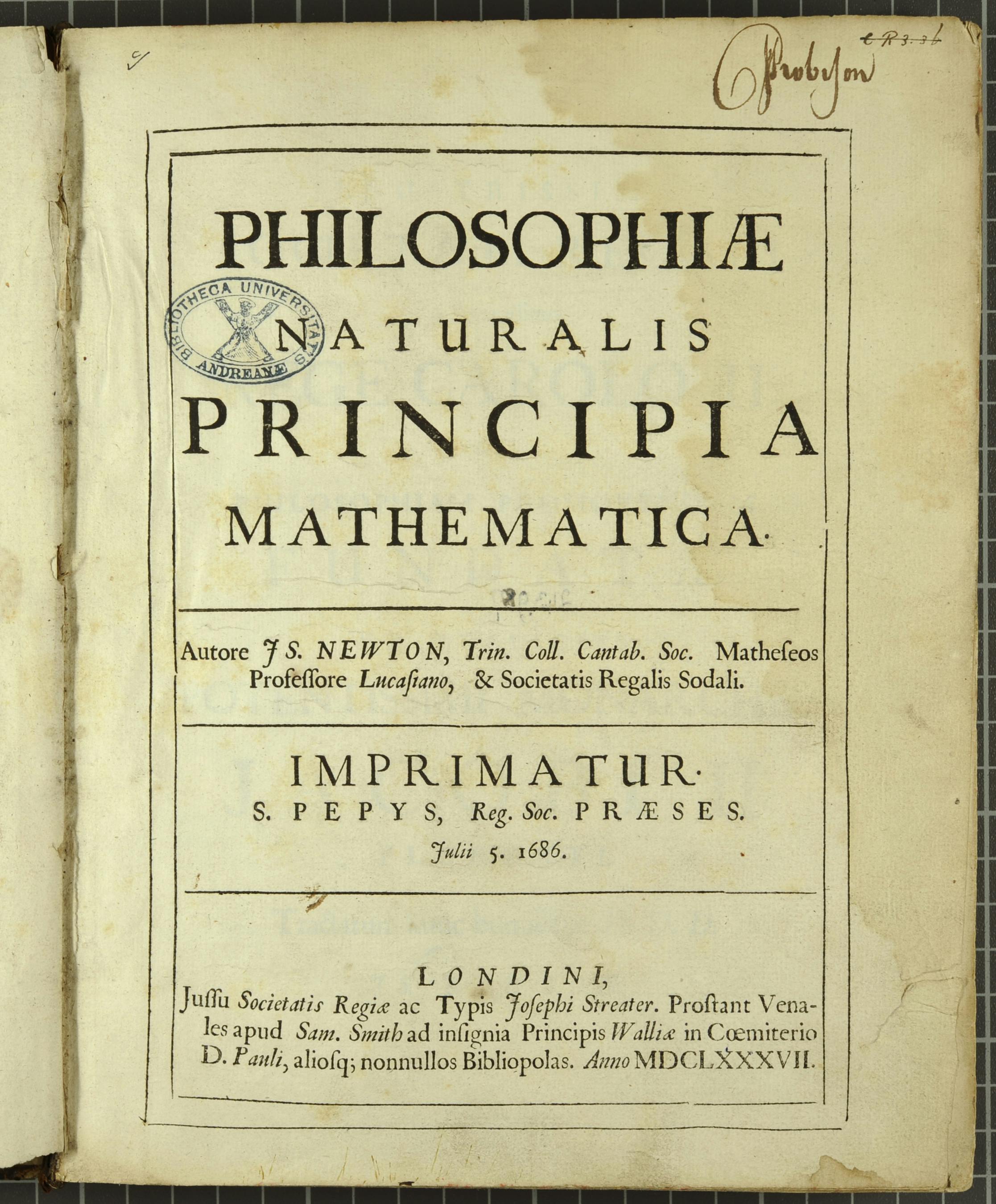

18th and 19th century book collectors were often more interested in a second or corrected edition of a work over a (textually) flawed first edition. For example, Isaac Newton’s seminal Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica was first published in 1687. By the early 18th century copies of the first edition had become expensive, largely due to their scarcity, and so Newton published a revised second edition that corrected several errors and expanded on his theories. This second edition became much more sought after by contemporary collectors. Now, of course, the rare first edition can sell on the open market for over $500,000; the second edition less than a tenth of that amount.

Fast forward to the 21st century, where the Internet has introduced a new era and fundamentally changed the way that librarians and collectors acquire books. 20 or 30 years ago, the pace and nature of collecting in the pre-Internet age was entirely different. The quiet, slow-paced paper-trail of rare book acquisition would begin with catalogs or short-lists which were mailed from an antiquarian seller; an item was identified by a librarian and checked against a card catalog; a series of letters were mailed back and forth; and finally a purchase was made. The whole process could take more than a month from beginning to end.

Now, booksellers have their complete inventories online and frequently e-mail out those short-lists. Librarians can search the Internet to find exactly what they need to build their collections with relative speed, rather than responding piecemeal to researchers’ needs or pinch hitting to fill gaps. Entire transactions take place in the matter of hours.

And the Internet has also changed what we collect: ephemeral printed material, for example, has found a new home in our collections recently, thanks to the availability of personal auction sites such as eBay. People now have ways to sell off posters and old letters from their garage or basement—letters and posters that may end up being an important missing piece of a library’s collection.

We still, of course, have certain parameters that help us to define and understand the idea of the rare book. The standard definition of what a “rare book,” as it stands, usually circles around a few factors: the date of publication, its scarcity in other libraries and the open market, and its intrinsic and financial value. Most libraries have a cut-off date for “rare” of somewhere between the 1840s and 1860s (the onset of industrial presses and popular book production), so that everything published before those dates would be automatically included into a rare books collection.

That means that in this day and age in many libraries, there are books sitting on the open shelves that are from, say, the 1880s—over 100 years old and probably falling apart. So, as we are starting to lose some of the documentary evidence of the readership of the late 19th and early 20th century, libraries are beginning to shift the cut-off date for “rare.”

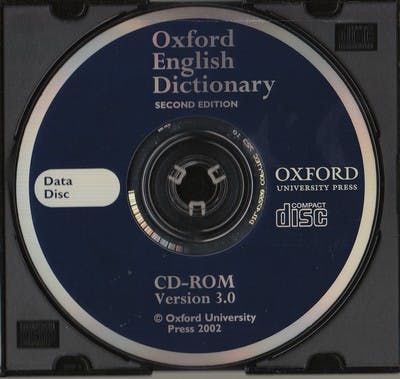

Aside from very old books, rare book collections are also a repository for valuable first editions, modern fine-press works, and other expensive books that might grow legs if left on the open shelf. Some collections aim to hold the entire publication history of a certain author or genre. The truth is that today rare book librarians and collectors don’t (and can’t afford to) just go after buying up all the first editions and old classics on the market, and first editions only tell the beginning of an idea’s, of a book’s, story. But we are the collectors and curators of the documentary heritage of our institutions, our regions, or our nations. How do we carry this calling forward into the Internet age? Surely a library’s first CD-ROM of the Oxford English Dictionary (with back-up 5 ¼” floppy discs!) belongs to our collective documentary heritage just as much as the OED’s first fascicles from the 1890s.

An individual book is, and will always be, an interesting artifact. The stories that an individual copy of a 500 year old book can tell are ceaselessly amazing—being able to visualize, for example. the voyage of one book printed in Venice in the 1530s, surviving centuries of plague and war in Europe, passing through the hands of many different collectors, and eventually arriving on the doorstep of a Library’s collection. This is a definite perk of the job. A collection of books tells a far more complete story than even any one book can. They capture a landscape, an era.

We must continue to foster the strength of a curated collection and the stories they tell, whatever the items are that we are collecting. Of course we can’t all collect one copy of everything printed ever; but a curated collection of the output of an author, or a genre, or a type of printing has the invaluable ability to enrich our understanding of who we are and who we were.

The Digital Age has changed how we, as professionals, talk about collections. In years past, each library was its own island, collecting what it could and putting on exhibitions and pushing out publications with their own material. No longer—we think about collaborative work, between libraries. Digital and physical exhibitions which feature material from multiple libraries are becoming more common, and libraries are even working together to build collections. This is due in large part to libraries making their collecting policies public and transparent, therefore eliminating duplicated collecting efforts.

The Digital Age has changed how we, as professionals, talk about collections. In years past, each library was its own island, collecting what it could and putting on exhibitions and pushing out publications with their own material. No longer—we think about collaborative work, between libraries. Digital and physical exhibitions which feature material from multiple libraries are becoming more common, and libraries are even working together to build collections. This is due in large part to libraries making their collecting policies public and transparent, therefore eliminating duplicated collecting efforts.

Rare book librarians are also engaging in digital humanities projects which try to virtually reassemble dispersed collections; they contribute to crowd-sourced cataloguing programs; and they are stepping into the conversation of large-scale visualization projects.

Still, what will it mean to curate collections of rare books when e-books are flooding more and more of the market? What does a book from the 21st century look like? Certainly the book has shifted in forms before, but it has gone through some incredible changes in the past two decades.

Consider the jump for an author like Ray Bradbury, for example, who published one of my favorite books in 1957, Dandelion Wine. This book was published by Doubleday in hardcover with a beautifully illustrated dust jacket. The cloth edition was followed in 1959 by a paperback edition from Bantam Books, and then subsequent mass market, popular (and cheap) editions. Then in 2006, Bradbury’s sequel to Dandelion Wine, Farewell Summer, was published by William Morrow in hardback, CD and cassette and MP3, with a paperback edition printed the following year. Farewell Summer has since seen at least three popular editions; last year it was finally released as an e-book.

So many different editions and ways to digest a book in such a short amount of time is indicative of the way that we, now, read books. It should also be the way that we now, as collectors and curators, collect books. What may not be deemed as rare today will most certainly be rare and collectable to someone centuries from now, especially as technologies change and methods of consumption veer further and further away from print culture. A new book sitting on your local bookseller’s shelf may one day end up in an exhibition case in a library or be a sought after edition by the antiquarian collector of the future.

The curious questions come with ideas about how our reading habits are changing. Now that our minds are used to reading with hyperlinks and not alphabetical indexes of books with pages and covers—what does this mean for the future of the rare book? How will we store these early treasures of this new generation, so that we can look back centuries from now and get a glimpse of the reading culture we are today? What is worth preserving, when there are no objects? And how do we preserve, when formats vary and change faster than you can buy a new reading device? Is the rare book collection over?

Hardly. It may feel new now that e-books are galloping through the publishing industry, but librarians and archivists have been grappling with the issue of preserving ‘born-digital’ material since the mid- 1990s. Universities, governments, businesses, and local authorities have been implementing policies on archiving e-mails, documents, images and anything else born digitally.

Hardly. It may feel new now that e-books are galloping through the publishing industry, but librarians and archivists have been grappling with the issue of preserving ‘born-digital’ material since the mid- 1990s. Universities, governments, businesses, and local authorities have been implementing policies on archiving e-mails, documents, images and anything else born digitally.

There are institutional collections of born-digital collections popping up all over the globe. The Computer & Video Game Archive at the Unviersity of Michigan is a great example of the successful preservation of software and hardware (helping us to avoid the dreaded digital obsolescence of the 8-bit Mario brothers and their pals). Most libraries, public and university, hold loads of floppy disks, tape drives, CD-ROMS that are considered to be in threat of becoming obsolete. These collections house what will surely be the equivalent of an e-Gutenberg Bible hundreds of years from now. The Hull History Centre, in collaboration with the Universities of Hull, Virginia, Stanford and Yale, have been developing models for the preservation for born digital material since 2009 in hopes of creating models for inter-institutional stewardship.

Maybe the future of printed books lies in this strange dichotomy that has been developing the past few years. As electronic editions of books flood the market, publishers may also return to a focus on the tangible details of what a makes a physical book so special. Many of the first editions of new, popular fiction have taken design and production queues from the fine press world, an art form that has seen renewed interest in the past two decades. High end production of books doesn’t need to become a rare, lost art-form, nor does it need to become a monument to what we have seen and lost. The beauty and limited nature of these productions—their heavy paper, beautiful fonts, their design and composition and meaningful bindings—all make physical books attractive for both the private and institutional collector.

There’s something almost melancholic about the beauty of a well-constructed book, something nostalgic which tugs at both the curator’s and collector’s heartstrings. A yearning for what once was. Like Leah Price said in her New York Times essay, “Dead Again”: “Every generation rewrites the book’s epitaph.” Maybe it’s time to stop trying to bury the book and accept that it’s not going anywhere.

There’s something almost melancholic about the beauty of a well-constructed book, something nostalgic which tugs at both the curator’s and collector’s heartstrings. A yearning for what once was. Like Leah Price said in her New York Times essay, “Dead Again”: “Every generation rewrites the book’s epitaph.” Maybe it’s time to stop trying to bury the book and accept that it’s not going anywhere.

Now we curators have to begin asking ourselves how do we prepare ourselves and our collections for the coming generations. We need to keep asking what it is that we should we be collecting, and how should we preserve it; how can we share our ideas most efficiently so that we are all on the same page.

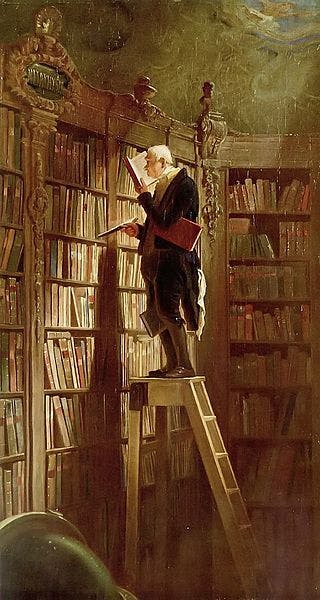

The role of the rare book librarian has changed with the onset of the digital age. No longer can we afford to be solely backward-looking in the dusty stacks. We must also look to the future; we must become a Janus for the book world with a finger on the pulse of contemporary reading trends while also keeping a firm grasp on the past. Aside from collecting the old, rare and precious books that help to define generations past, we should be looking to what people are writing, reading and creating now.

The role of the rare book librarian has changed with the onset of the digital age. No longer can we afford to be solely backward-looking in the dusty stacks. We must also look to the future; we must become a Janus for the book world with a finger on the pulse of contemporary reading trends while also keeping a firm grasp on the past. Aside from collecting the old, rare and precious books that help to define generations past, we should be looking to what people are writing, reading and creating now.

The attitude of letting history sort out what should remain in the popular canon of literature is out of date. The flops of a generation tell as much as a best seller about a certain time and attitude towards ideas. Rare book librarians have always had to play catch-up when it comes to buying up copies of first editions of modern authors—a game which can come at quite a financial cost (consider the cost of first editions of Rowling, Hammett or Tolkien, now highly sought after to complete collections of children’s, pulp and fantasy literature). If we can identify contemporary authors or trends which are important to our respective collections now, we can develop relationships with these creators and add to our collections with these intentions, and future generations of librarians and scholars will be better for it.

This column is part of The Way We Think series. What happens when you get past the buzzwords and take a broader look at what the Internet is actually doing to transform our culture, our research, our tastes, and our ideas? In this series, the Daily Dot will publish major thinkers and fresh voices from diverse areas of our intellectual and cultural lives—science, literary criticsm, photography, food blogging, biology, art history, wine, travel—on how our world is changing in concrete terms because of the Web.

Daryl Green received his M.A. in Medieval Studies from the University of York in 2007 and trained at York Minster Library before heading to the University of Illinois in 2009 to pursue his MLIS and Certificate in Special Collections. There he worked for the Rare Book and Manuscript Library as a cataloger and co-founder of Non Solus: a blog for booklovers. Daryl began work at the University of St Andrews in 2010 as Rare Books Cataloguer, and in 2011 he created Echoes from the Vault: a blog from Special Collections of the University of St Andrews, of which he is currently the editor and chief contributor. He has now taken on the role of Acting Rare Books Librarian as of April 2012.

Images: Rare books at University of St Andrews; Newton’s Principia, University of St Andrews; Oxford English Dictionary CD-ROM, 2.0, Oxford University Press; The Bookworm by Spitzweg; Janus, by Ultima Thule, 1927 (Ultima Thule, 1927) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.