I’ll never forget attending the last tribute to Julia Child. It was organized by Boston’s cohort of culinary historians, on a Sunday afternoon in Cambridge at Radcliffe College. The luminaries who spoke—her WGBH TV show producer, her suppliers, high-star Boston chefs—were local. The event was as low key as it could be, yet Julia put up a fuss and refused to come. “I don’t want to hear people talk about me,” she told the historians. “I’m going to be too embarrassed sitting there.” In the end, she boycotted the classroom with podium and microphone, but showed up for the tea reception.

The modesty of the event turned out to be its own tribute. Speaker after speaker stepped to the front of a dreary Cambridge classroom, took the microphone and said, with astonishing unanimity, that what made Julia Child exceptional was not just that she really did know how to cook. It was more her staunch refusal to use that cred to endorse a product, or sell a brand, or pitch a restaurant. The neutrality she so fiercely guarded endowed her with an undiluted integrity that made everyone totally trust her. They knew she had no interest in monetary glory or empire building, only in—as the title of her last book said—The Way to Cook.

Who can we say that about today?

Julia Child pioneered cooking as public spectacle and single-handedly made it sustenance for the media. But what she actually carefully concocted and served was instruction. To her, a knife was strictly for kitchen work; she was on “educational TV” (as public television was then known) showing how to pare, bone and carve with one. She did not brand the knife, but brandished it—because her only agenda was to help us get a grip.

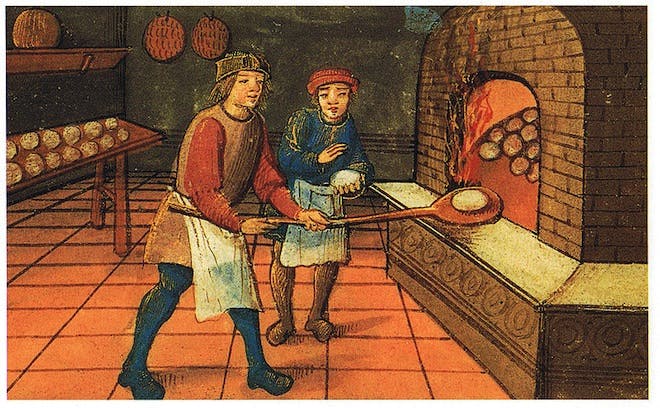

What would she think today’s cooking/feeding frenzy? The media has monetized the public spectacle of cooking the only way it knows how. Cooking has become blood sport, like Roman bread and circus. If it isn’t gripping “chopped” gladiator competitions, it’s knives used to stab a fellow cook in the back with badmouth contests that make the likes of Gordon Ramsey more famous for tasteless retorts than tasty food.

What would she think today’s cooking/feeding frenzy? The media has monetized the public spectacle of cooking the only way it knows how. Cooking has become blood sport, like Roman bread and circus. If it isn’t gripping “chopped” gladiator competitions, it’s knives used to stab a fellow cook in the back with badmouth contests that make the likes of Gordon Ramsey more famous for tasteless retorts than tasty food.

The excitement of killer competition evidently creates such ka-ching that even the venerable New York Times in its early December’s digital edition ginned up a catfight between two food reporters presenting their edible holiday presents. “These are the food gifts Julia Moskin and I decided to go to war over,” Kim Severson explained. “Though we really are the best of friends, sometimes being right (especially about what’s on one’s plate) matters… .” Readers could vote by tweet or email for which writer gave the best food gifts. And 829 readers did. I ask those readers: What did you learn about cheese straws that improved your life or your skills?

If we want genuine thrills, homemade, handmade food gifts should be encouraged on a holiday that’s supposed to be about caring, renewed life, and love. Jam, cheese straws and pickles are personal, a giving of yourself, and that’s supposed to be the point. The only real point. At this moment of greatest darkness, we are meant to be bodies of light, which is to say, to help each other through the night. What makes edible gifts de-lightful is the effort made when fresh food supplies are scarce to remove the dark, primal fear of starvation. Gifts of life are the gift of love. Handmade food is local, sustainable and ecological. There should be no worries about size or color, no worries about how glamorous the end product is in a photograph, about broadcasting it to countless strangers.

You will not get these tidings of comfort and joy in a food blog, not even one entitled “The Year in Food” or “Food 52,” whose title implies week by week food endeavors. Huffington Post Food tantalized us with an array of glossy photos and recipes for different holiday cookies. In many European countries, making cookies with the spices known to heat and thus help the human body—ginger, cinnamon, clove—is a longstanding, beloved Christmas tradition. At the same time as seeing that contest, I received an email from a friend in Frankfurt, Germany, telling me how precious it was for her to bake cookies with her 9-year-old granddaughter. “The house smells wonderful,” she wrote. “It was so much fun being together with my little (very tall) grandstar.”

You will not get these tidings of comfort and joy in a food blog, not even one entitled “The Year in Food” or “Food 52,” whose title implies week by week food endeavors. Huffington Post Food tantalized us with an array of glossy photos and recipes for different holiday cookies. In many European countries, making cookies with the spices known to heat and thus help the human body—ginger, cinnamon, clove—is a longstanding, beloved Christmas tradition. At the same time as seeing that contest, I received an email from a friend in Frankfurt, Germany, telling me how precious it was for her to bake cookies with her 9-year-old granddaughter. “The house smells wonderful,” she wrote. “It was so much fun being together with my little (very tall) grandstar.”

There’s the kind of family time we crave, the stuff of comforting bonds and joyful memories. But, jingle bells, the Huffington Post didn’t put all those cookies on its printing plate to encourage that. It presented the cookies like everything gets presented nowadays: as a horse race. In our winner-obsessed culture, everything has to be competition, so the Huffington Post wanted people not to find joy in making holiday cookies that warm you, but to vote for the best one. Or use the cookies to create a competition among your friends. Hopefully you’ll be Number One.

The Internet has made the most important kitchen tool no longer the knife, or the rolling pin, but the camera. If you can’t take stunning, high resolution photographs of your work, you don’t count as a cook. They are indeed stunning photographs: the luscious, carefully styled, pornographic kind. Those photos arouse you. They get your blood racing, your stomach pumping. You are excited and want closure, satisfaction… You want to eat that right now.

The Internet has made the most important kitchen tool no longer the knife, or the rolling pin, but the camera. If you can’t take stunning, high resolution photographs of your work, you don’t count as a cook. They are indeed stunning photographs: the luscious, carefully styled, pornographic kind. Those photos arouse you. They get your blood racing, your stomach pumping. You are excited and want closure, satisfaction… You want to eat that right now.

Bah, humbug. Those of us who can’t make a dish look so perfectly luscious are probably going to feel inadequate and pass on learning to cook. This problem emerged in the ‘80s when “food stylists” surfaced on the glossy pages of slick food magazines to make food porn. Their spin and hype served the collective imagination sirloin steaks with perfectly painted black grill lines or desserts made shiny by varnish—all sorts of trumped up photos that made real people stop trying to cook because they just couldn’t get that picture-perfect effect. Or worse, they complained to caterers and restaurant chefs who were serving up the real deal that their food somehow didn’t look right.

Julia Child was widely revered for constantly saying: “Never explain and never apologize.” She wanted us to simply serve the food and let it speak for itself. But today’s bloggers don’t just serve up recipes and techniques. They serve themselves, plating up explanations and apologies. “Bourbon, two weeks in a row? Well, it’s December. It’s December and I’m snowed under piles of work.”

Bloggers whisper sweet nothings, so we get to know they’re sitting on the kitchen floor desperately staring into the oven to watch the cannelé rise. Or they smite us with their issues: “My name is Deb Perelman and I have a fritter problem. And I really do. I pretty much want to fritter all the things, all the time …, I actually have to hold myself back, and try to evenly space my fritter episodes throughout the year, so not to pique your concern about my fritter consumption.” Food blogs are not so much about cooking as about exhibitionists letting us peep at private lives in hopes we will be, ahem, smitten, a word usually applied to sexual attraction.

It’s understandable that life in what’s more often than not an impersonal, inhumane and isolating society makes us yearn for the warm humanity of the kitchen. There’s so much joy to the world there. Food is life—the word hospital comes out of the word hospitality. If they blogged, the ancients could have told you: feeding people gives them health. That gives them comfort. Feel the love.

Food is our connection to the earth, sky and sea. It’s feng shui harmonizing us with our surroundings. Food is our link to each other, to everybody out there, for food is the one same need everyone–regardless of their financial percentile, political state, geographical region, age, gender, dress, whatever—shares in common. And because even with supersonic jets and superfast electronics, we would not be alive if that need isn’t met, we share food, share the labor and love of it, share recipes. Eating makes us all one big community, and people starved for communion are clicking away for that.

Julia’s tribute was held at Radcliffe College, which had amassed the largest collection of community cookbooks in the world. The culinary historians saw these as sociological treasures: anthropological documents that revealed the inner secrets of a neighborhood. Their insight was that ingredients and utensils in recipes provide a financial, educational, and social portrait. This is also true of the Internet’s food blog buffet. On full display is how hungry we are to be seductive and to be number one; how obsessed we are by excitement. Sadly, what’s harder to see or taste is the way to cook.

Sandra Garson is the author of Veggiyana, the Dharma of Cooking and How to Fix a Leek and Other Food from Your Farmers’ Market. She is the founder and president of the Buddhist food charity Veggiyana and maintains its news blog. She recently spent six weeks teaching vegetarian cooking in meat-obsessed Mongolia, and is working on a second helping of Veggiyana recipes and essays as well as a way to teach children the magic of cooking.

Art credits: Culinary weapons by canongate; Julia Child in The French Chef via KQED.org; Mrs. Ecequiel Irene cooking from Library of Congress; Holiday cookies by Michael’s Cookie Jar; food picture by goldberg; Medieval bakers via Wikiepedia, from the Bodleian Library, Oxford.