Video game clones have been around as long as there have been video games, but lately they seem to be overshadowing the originals. You can see that in the rise of the Threes clone 2048 and the flock of Flappy Bird imitators initially prompted by the game’s inexplicable popularity and then its unexpected and untimely demise

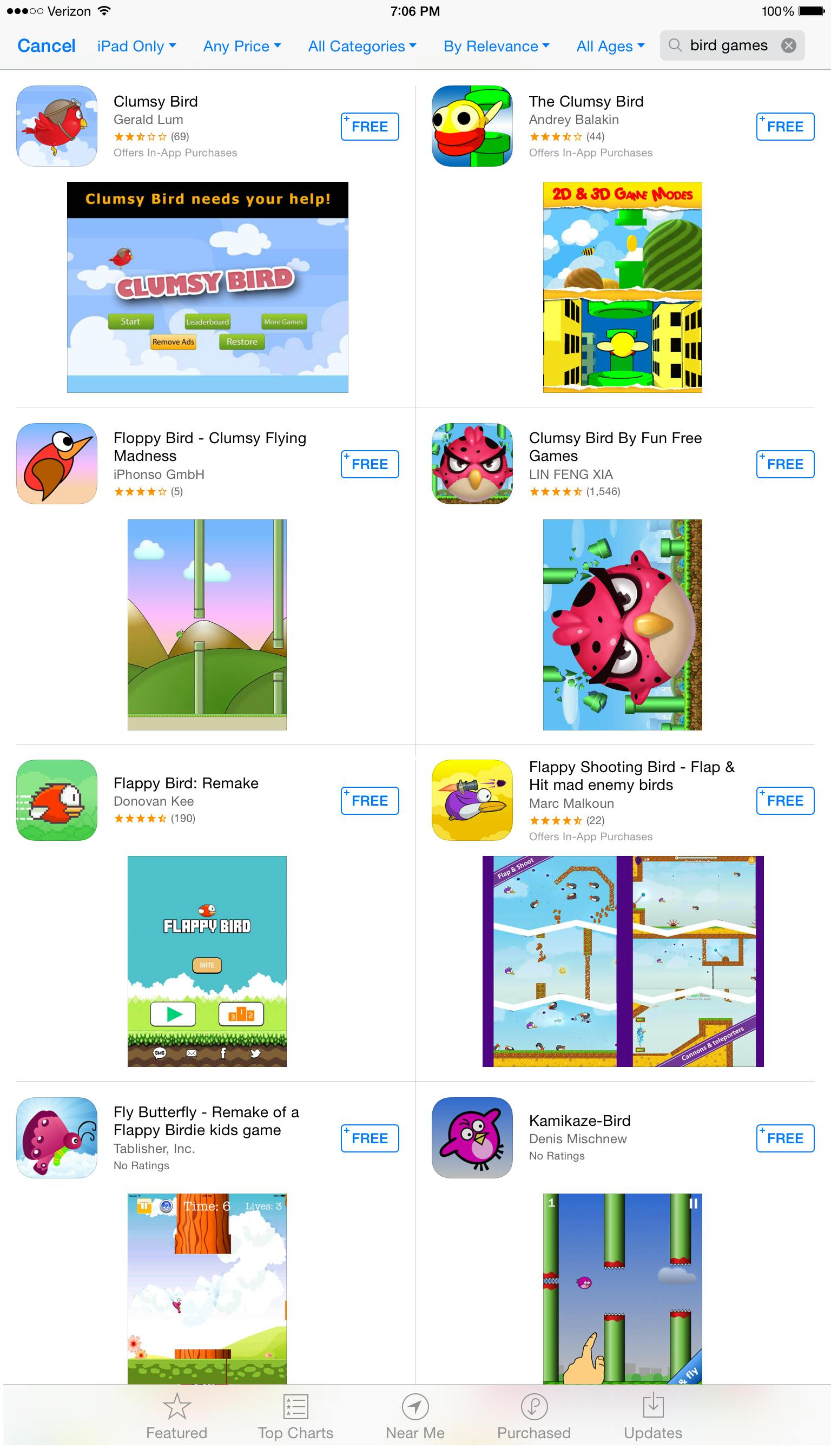

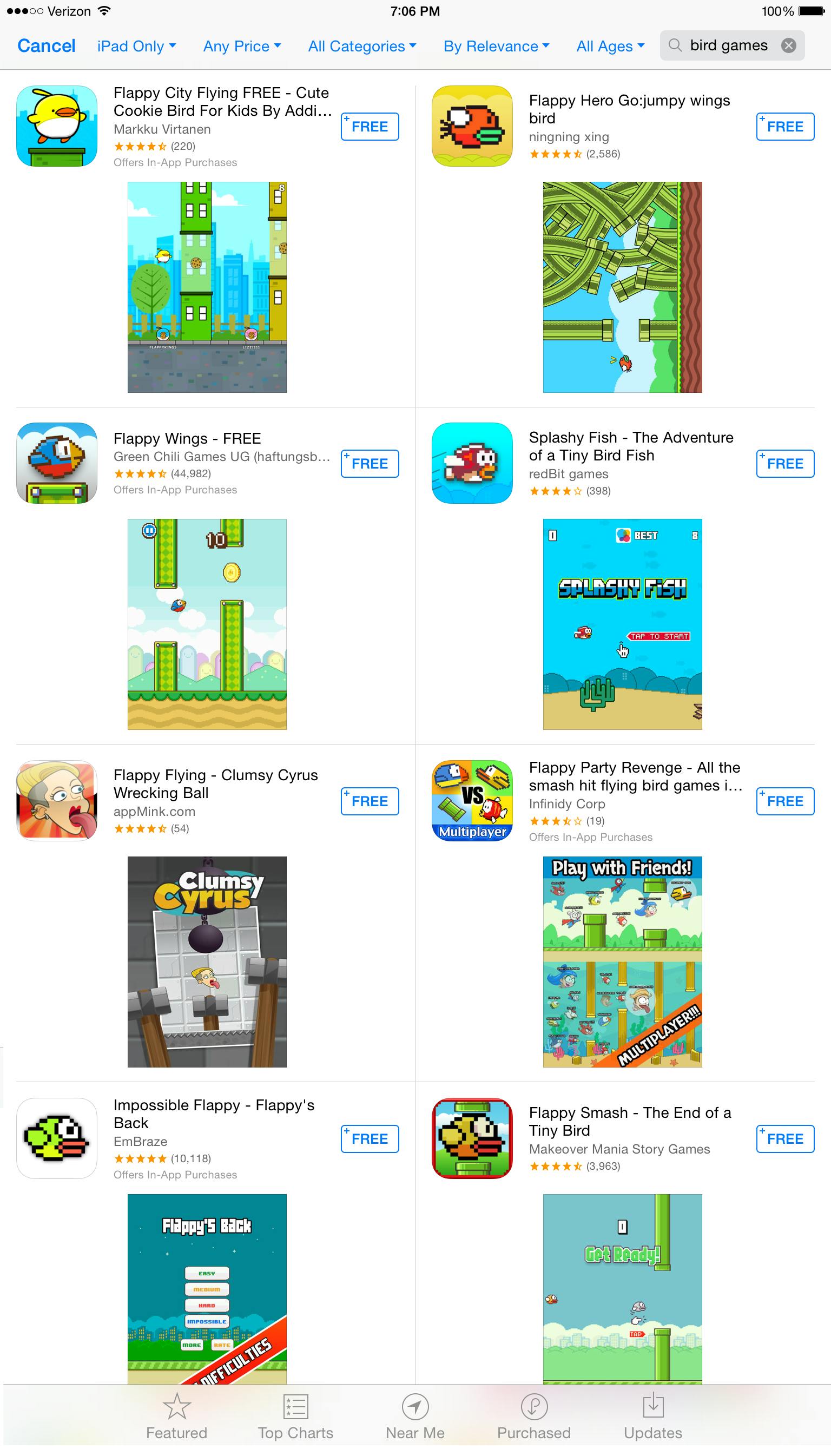

The members of the Flappy Bird clone army include Snappy Bird, Floppy Bird, Clumsy Bird, Flappy Smash, Flappy City Flying, Flappy Hero, Flappy Party Revenge, Splashy Fish, and of course, Clumsy Cyrus Wrecking Ball. They’re mostly cheap, uncreative, and generally terrible, which raises some interesting questions: Why do people make terrible copies of popular games, and why do so many people play them?

At first, it seems obvious why people would create cheap knock-off games: to make money. Anyone who has played copycat games knows that they are usually riddled with ads, much more than original games tend to be. The worst offenders often feel no better than spam-delivery machines.

READ MORE:

The definitive guide to winning 2048

In fact, from the perspective of revenue-generation, very cheap knock-off games work on the same principle as domain-squatter websites and content farms. You can put up a cheap website based on a click-bait concept (“Flappy Miley Cyrus,” anyone?) with 20 percent content that at least looks real and 80 percent advertising, and hope that enough people accidentally click on something to give you a reasonable revenue. At that point, generating income is just a statistics game.

But click-bait revenue can only be part of the explanation for the popularity of cheap knock-off games. Despite what cynics may think, income usually isn’t the main motivation developers have for copying games. Certainly, it was not the main motivation in the past. The best illustration of this can be found in one of the most popular and often-copied games of all time: an ancient computer game that has been around for almost half a century.

In Russia, Tetris plays you

The best thing to come out of the Soviet Union during the Cold War was Tetris. Very much like Flappy Bird, the concept was simple, and the actual play could be surprisingly difficult as time went on. Also, the graphics were terrible, although this almost goes without saying since it was invented in 1984.

Over the decades there have been dozens if not hundreds of clones, copies, and variations. There are three-dimensional versions, versions that include words or faces on the falling blocks, versions that introduce completely different puzzle shapes, and versions that add weird physics to the falling pieces. Some are officially licenced copies, others have been embroiled in lawsuits. You can play a selection of almost two dozen of them over at playtetrisgames.org. Tetris Company LLC has been sending cease-and-desist letters to Google for years in an attempt to manage the availability of free copies of Tetris, largely with no effect.

Even back in the 1980s, simple free versions of Tetris were available for your IBM-PC, Mac, Amiga, or Commodore 64. They were not official or approved copies, had no advertising, and generated no income. The reason Tetris was so readily available for free to almost any computer platform in the universe was that hobbyist programmers were all swarming to make their own versions.

In the 1980s, when almost anyone who owned a personal computer was a “computer hobbyist” to one extent or another, the challenge of recreating a game like Tetris from scratch was a game unto itself. I speak from personal experience: When I was a young student, I was a dedicated fan of the game. I had Tetris, Hatris, Welltris, and a variety of other versions on my IBM-PC. The idea of figuring out how to build my own Tetris was exciting simply because I was a fan. For a programmer, rewriting your favorite game from scratch is the equivalent of creating fanart, or writing fanfiction. You do it was a way of having a more personal connection to the thing that you love.

The ASCII version of Tetris (written in BASIC) that I wrote when I was 14 didn’t make me any money, but that wasn’t the point. It was fun and educational, and Tetris continues to hold up on both fronts to this day. There are tutorials for programming Tetris in C/C++, in Javascript, and in Flash, to name just a few examples. And if you are truly a hardcore engineering type, you can learn how to create Tetris using AND and OR logic gates.

What does all of this history about Tetris have to do with the gaming industry today? Because exactly the same thing is part of today’s Flappy Bird phenomenon: There is already a “Flappy programming game” designed to teach student programmers the principles of modular program design. You can buy the source code for a software package called Flappy Crocodile, which allows you to look at the source code for a Flappy Bird-like game, and customize it to your heart’s content.

You can bet that examples of source code for simple versions of Flappy Bird will soon be available in many other programming languages, along with in-depth tutorials and how-to guides. Then nothing will be able to stop the mass proliferation of flappy, floppy, and clumsy games across the Internet and mobile devices—even if it nobody makes money from it.

Fads, fashion, and imitation

When sociologists study imitation in fashion, they almost always talk about it in terms of status and social climbing. Some of the earliest sociological theory on fashion trends comes from the classic work of Georg Simmel, who studied fashion cycles in 19th-century European societies. According to Simmel’s view, innovative new fashions originated among aristocrats and then was imitated by people of the lower classes who aspired to be more like, or at least appear more like, those of higher social standing. Once the higher classes caught on that people of “lower breeding” were wearing a certain style, they would drop it immediately and move on to something else. Thus fashions would constantly be driven towards something new through an ongoing process of imitation (by the lower classes) and differentiation (by the upper classes).

Video games are not clothing styles, and what is considered “elite” by today’s gamers certainly has nothing to do with 19th-century class structure. Yet some of the same principles of fashion and imitation still apply. After all, playing a game has never been a purely private phenomenon. Even before mobile and hand-held devices let you carry your games to parties and play them on the bus, gamers were forming social circles based around common interests in games.

In addition to being fun to play, Flappy Bird was an instant social phenomenon. It spurred debates and discussions, and at least part of its popularity was fueled by the desire to be someone who was in on this new popular phenomenon.

SEE ALSO:

Why you can’t stop playing Flappy Bird

Then, Dong Nguyen, the creator of Flappy Bird, pulled the plug. It’s hard to imagine anything that he might have done to generate even more popularity and news. Suddenly, playing Flappy Bird or any of its clone variations became even more of a conversation piece, if not an actual “status symbol” per se. Having the latest variation of Flappy Bird could now symbolize something special, at least within a particular community of gamers. When gamers saw someone on the subway playing Flappy Bird, or some variation, it could instantly be a reason to start up a conversation. Which version is this? How did you get it? What is it like?

It isn’t necessarily fair to accuse Nguyen of pulling the plug on the original game as a publicity stunt. After all, he did claim to have his own reasons, including his own psychological well-being. However, it would be difficult to argue that his removal of the game didn’t fuel the fire behind the ever-increasing popularity of the phenomenon. In much the same way that everybody wants to read the banned book or see the movie that their pastor warned them about, the official removal of the original Flappy Bird game made it only more powerful as a social force.

When will it end?

As Georg Simmel observed, fashions come and go. Right now, cheap copies of games are in, and the Flappy clones occupy a special place in history as a phenomenon where the ridiculously cheap copies have outpaced the original. This may be the first time that it has happened, at least since Tetris. But there should be little fear that this represents a permanent trend: a death spiral into a world where the only new games being created are 99-cent copycats and spin-offs.

Social trends push the envelope from time to time, especially when somebody finds a formula that seems both cheap and successful. The same thing happened with movies and television shows in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Between television shows like The Real World and movies like Blair Witch Project, which took $60,000 to make but grossed almost $249 million worldwide, producers felt they had discovered a formula for making hits for almost no money.

It was a trend for a while, and for a while the media fretted that the future of all movies and television would be unscripted programming and shaky hand-held cameras. Luckily, people got sick of that trend. As Larry Gerbrandt of Kagan World Media said in 2001, “There was a time when people thought that Blair Witch Project was going to be the undoing of Hollywood, because you’re going to have people running around with video cameras, competing with the studios. As it turns out, Blair Witch was the exception, not the rule. And it certainly wasn’t the future of the business.”

Reality television is still around, of course, but it hasn’t replaced television dramas. We see relatively few new movies using grainy hand-held video cameras, “found footage,” and questionable lighting techniques to add to the drama of horror scenes. The simple fact is, people got sick of the low-budget gimmicks, and the industry moved on.

People will become sick of the Flappy clones, too, eventually. Just give it time.

Illustration by Jason Reed