BY CHRIS OSTENDORF

The first rule of Fight Club is, you do not talk about Fight Club—unless of course you love Fight Club, in which case you probably talk about it all the time.

Now, it seems we may all be talking about Fight Club once more. Author Chuck Palahniuk announced this week that he will be writing a sequel to his breakout novel, due to be released in 2015, in the form of a ten-issue “maxiseries.” Illustrator Cameron Stewart is set to provide the artistic component of this endeavour, which will explore the future of the narrator, now married to love interest Marla Singer, as well as the origins of (fifteen-year-old Spoiler Alert) his alter-ego, Tyler Durden.

It’s impossible to talk about the story of Fight Club without also talking about the iconic 1999 film it was adapted into. Although the movie was not quite as maligned upon its initial release as legend would have it, it certainly wasn’t well-liked by many, and it certainly didn’t achieve its now mythic status overnight.

Fight Club’s position as a cult classic has certainly been widely discussed, although that title feels like somewhat of a misnomer in a world where collective knowledge of the film is so ubiquitous. It always hovers somewhere around the highest spots in the fanboyish ranking of the IMDb top 250, and in 2008, Empire magazine named it the 10th greatest movie of all time, and Tyler Durden the greatest movie character ever (up there with other dorm room poster staples such as Darth Vader, The Joker, The Dude, Vito Corleone, and Ellen Ripley, the one female character to crack their top 10).

Today, Fight Club is able to live on in part thanks to the rampant analysis that comes with Internet culture. Filled with easter eggs and hidden details, it’s the exact kind of movie that’s ripe for online discussion.

And it is impossible, when discussing this discussion, not to focus at least in part on the passion the movie has elicited from straight white men. Take a look at Reddit or any other major hive of Internet activity, and you’re sure to find conversations about why Fight Club’s portrayal of modern masculinity continues to entice. Indeed, the fervor around the film has become so great, several notorious “real life” fight clubs have popped up in the years since its release.

There is plenty of reason for this to inspire concern. Considering America’s current masculinity crisis, some of the film’s more famous lines, like Tyler’s assertion that, “We’re a generation of men raised by women. I’m wondering if another woman is really the answer we need,” may warrant some head-shaking, assuming they’re being taken too seriously.

But that’s the thing: Fight Club is not a movie to be taken too seriously. It makes many valid points in its critique of consumerism and selfhood, but tying those points into masculinity specifically is always going to be an empty exercise. With the sequel coming in 2015, its time to reexamine what we talk about when we talk about Fight Club, as well as how our feelings about it will likely influence the way we perceive the second part of the story.

Being interviewed about her podcast, Fucking While Feminist, by the Washington City Paper, writer Jaclyn Friedman made it clear her distaste for Fight Club was strong enough that in online dating, “I used to look for guys who don’t list Fight Club in their favorites, but I’ve had to relax that rule, because all dudes evidently love Fight Club.”

Friedman most likely wouldn’t be alone in seeing Fight Club as a red flag. Just as persistent love for Fight Club is also ever present on the Internet, you don’t have to look far to find a litany of blog posts bashing it. Marit Bayeur at Entertainment: Scene 360 sums up the stance of many who have critiqued the movie’s supposed depiction of repressed and emasculated manhood. She writes, “Although the film presents itself as a critique of capitalist consumer culture (lamenting how men are stifled under an oppressive maternal-material), it does not challenge, but rather reinforces, the inherent oppressiveness of binary-dependent roles in which liberation is contingent on subjugation, and masculinity is defined by a Freudian castration of femininity.”

The other major area where people continue to delve into and frequently criticize Fight Club is academia. And why not: It’s the perfect sort of pop movie that has enough substance, but is also widely seen enough, to make for a good lecture topic (see also: The Matrix). University of Rhode Island professor Kule Kusz recalled a time on the Feminist Wire where he almost made a student cry, following an argument about manhood; one of the student’s favorite movies was Fight Club.

For many, a particularly negative aspect of the film is its female lead, Marla Singer, played with typical gusto by Helena Bonham Carter. At the beginning of the movie, Marla and the narrator have an antagonistic relationship, almost like one out of a twisted romantic comedy. But as Marla begins a dalliance with Tyler, things get complicated. In the film’s finale, the narrator “saves” her from certain death, and they end up holding hands while watching the unnamed city where the story is set crumble around them.

On the college academic journal, Student Pulse, Tori E. Godfree dissected the tricky gender dynamics between Marla and the narrator, whom she calls “Jack.” “The impression we are left with at the end of Fight Club is that the rearrangement of Marla and Jack’s masculine and feminine traits leads them to become better people,” Godfree posits. “Marla, as a more feminine woman, is more tender towards Jack, and thus more appealing to him. Jack, as a more masculine man, is more confident towards Marla, and thus more appealing to her. This suggests that only through the proper alignment of masculine and feminine traits can one truly achieve good character and proper ethos.”

Another student, named Logan Phillips, called the film out for what he characterized as hypocrisy. Posting an essay to everything2, Phillips claimed, “What makes the sexism in Fight Club most ironic is how clearly it comes in conflict with the main characters’ philosophies. Tyler explains to the Commissioner of Police that ‘The people you are after are the people you depend on. We cook your meals. We haul your trash. We drive your ambulances. We guard you while you sleep.’ Are we to believe women serve none of these functions in our society?”

And yet, what Phillips might be missing here is the idea that Fight Club is supposed to be ironic. Irony or not, it’s certainly fair to consider the film under a feminist lens, especially in a culture where sexism is either intentionally or unintentionally a part of so much of the media we consume. Nevertheless, there’s merit in considering the possibility that maybe the fanboys who have interpreted Fight Club’s themes literally and even taken them to heart, are missing the point.

For one thing, it’s worth taking into account the story’s source. Chuck Palahniuk is an openly gay man whose recent works have been equally outrageous but decidedly more campy and less sullen than Fight Club.

Then there’s David Fincher. Working from a screenplay by Jim Uhls, Fincher (who has helmed many films that are unashamedly “manly,” at least on paper) directs Fight Club with the same urgency to dive headfirst into gender issues that he has in much of his other recent works. The Social Network, for instance, was in some ways a condemnation of the same kind of sexist attitudes which the movie itself was also accused of having.

Of course, to call the film out on discernable sexism isn’t a bad thing, although whether one feels Fincher was successful or not, he deserves some credit for at least trying to start a dialogue about an issue which precious few other filmmakers appear to be interested in. Undoubtedly, his latest effort, another adaptation, this time of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, is certain to spark similar discussion.

What Fight Club ultimately reads as, assuming one does not take it literally, is satire. The Huffington Post’s Kim Morgan wrote as much when she broke down the film 10 years after its release. Morgan states, “Because Fight Club is essentially a satire, it knows that though Tyler’s eloquent assertions make sense, and are emboldening, they will become borderline fascistic and not entirely reliable.”

Looking at Fight Club through this lens, we see that Tyler Durden does not exist to embolden the men of his generation as much as to chastise them. These are a group of whiny, boring, nobodies, looking for someone to blame for the manner in which society has failed them, and Tyler’s prophecies become a way for them to blame society as a whole. Never do they truly look inward, and are instead content to rally against IKEA for feminizing their lifestyles, rather than doing any self-actualization. It’s violence over thought, as they embrace the “fascistic” new world order Tyler calls for, barely realizing that they are just becoming a part of another homogenized collective.

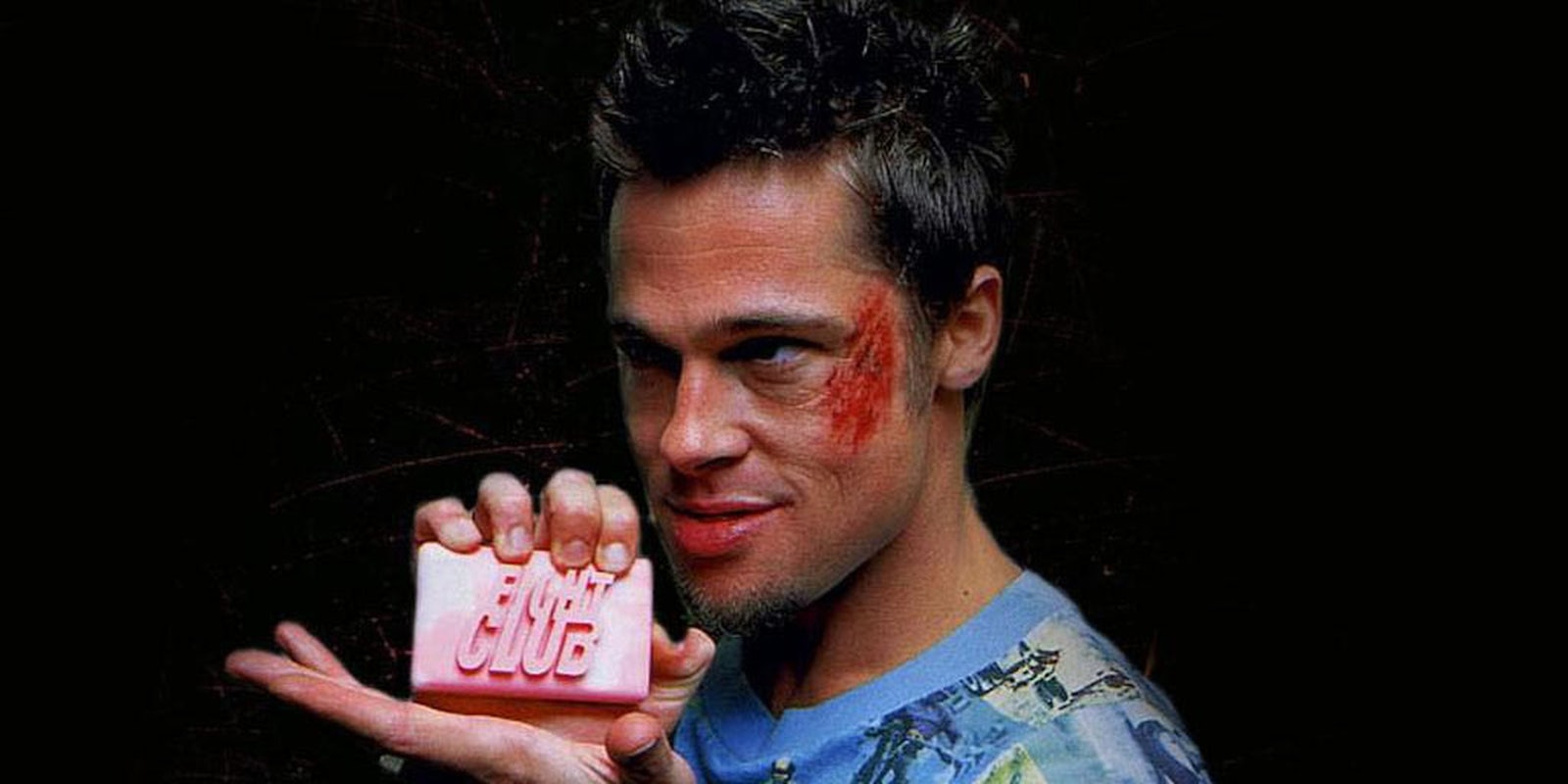

And Tyler himself is part of the joke, too. This is a guy who makes fun of the way men look in underwear ads, who happens to be played by one of the best-looking guys on the planet. He espouses notions of rugged individualism but also makes it pretty clear that “you are not special.” Meanwhile, he is treated as special by everyone around him.

And although he preaches a lot about reclaiming some kind of ideal version of heterosexual manhood, all those shirtless men in the film create rather potent homoerotic undertones. The close bond between Tyler and the narrator alone, even if it was all in the former’s mind, sets this kind of speculation up. At one point, the narrator actually refers to them as “Ozzie and Harriet,” and their closeness is only disrupted when Tyler begins a sexual relationship with another person, leaving the narrator with a “broken heart.”

Even in the end, as the narrator watches the destruction he has wrought, there is a sense that it is Marla who is the key element. She has brought him back to reality. After all the talk about reclaiming the identity of men from women, it is a woman who pulls him out of the darkness. If anything, it’s she who saves him (whether that almost makes her a riff on the “manic pixie dream girl,” or a deux ex machina, as Scott Tobias would tell you, is a conversation for another day).

Some have gone so far as to say that Fight Club is almost feminist it its depiction of masculinity. This might sound like a stretch, but Jennifer Kesler of the The Hathor Legacy makes a surprisingly convincing argument.

I’ll take one part of Tyler’s speech and raise it by a point: advertising does a lot worse than keep us chasing crap we don’t need so that we’re too busy to actually achieve anything that might overturn the powermongers at the top of the food chain. It has been pandering to the weakest instincts in young men and boys for a couple of generations now. 18-25 year old white boys don’t want to see strong women? Solution: don’t put a strong woman in your movie! For heaven’s sake, don’t show them that a woman can be strong and traditionally “feminine.” Or that a woman can be rather manly and still extremely sexy and attractive to manly men. Or that a woman can be a failure, and the failure have nothing to do with her gender.

But you don’t need to view Fight Club as a feminist film to recognize it as great satire—nor do you need to shy away from the purported sexist elements of the movie either. Fight Club is the kind of film that has endured because it produces strong reactions. On the one hand, it’s easy to see why a bunch of fedora-wearing, jean shorts-owning, Boondock Saints-loving, high school “nice guys” would turn to it as an almost religious text.

However, on the other, those who have been removed from high school long enough and seen enough of the world know a good bit of contradiction when they see one. And what makes a satire compelling is its ability to use contradiction to find truth. And the truth is that of a bunch of dudes blowing up a building in protest of corporate fascism, only to usher in a different kind of fascism entirely, is a huge contradiction.

Unfortunately, the Fight Club sequel is all too likely to pit the defenders and the attackers of the movie against each other. Whether it makes it to the screen or not (which, for many reasons, seems unlikely), the old arguments will surely come up, and the result could very well be a shouting match, as is most common in the age of the Internet.

That’s too bad, because in the wake of recent financial collapse—as well as our growing technological obsession—Fight Club’s original ideas on corporate culture and consumerism could be updated in a really interesting way. Whether the sequel is good or not though, the best outcome would be if it got people talking about masculinity intelligently and rationally. Because that’s a conversation that’s always worth having.

In discussing the sequel for The Telegraph, Tom Fordy said that, “Masculinity’s an anomaly—hugely important to us, but also a complete mystery. As long as that’s the case, the characters of Fight Club will have more than enough reason to punch each other in the face in trying to uncover the truth about it.”

Maybe Fordy is right, and masculinity is a mystery, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about it. And if a Fight Club sequel got people to do as much, that wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

Chris Osterndorf is a graduate of DePaul University’s Digital Cinema program. He is a contributor at HeaveMedia.com, where he regularly writes about TV and pop culture.

Photo via Fight Club/Fox