I found out my brother Matt had committed suicide from a status update on Facebook.

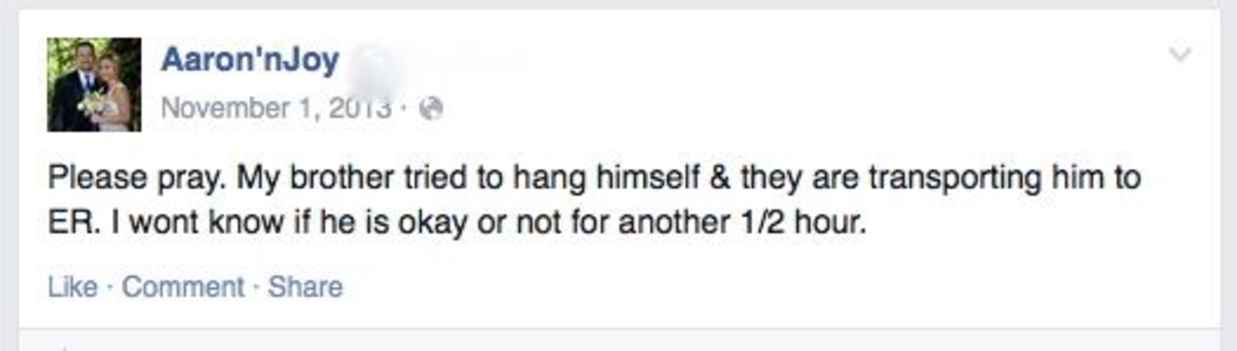

I had moved to Shanghai three weeks earlier and hadn’t gotten a cell phone yet. The only way to reach me was through Facebook and Skype. After work one night, I logged onto Facebook and saw my sister Joy’s status update. I sat and stared at the computer screen for several minutes before I felt like I could do anything.

Eventually I called my Mom, and the whole thing started to unfold. The hospital had called Joy late at night to tell her about our brother, and she was home alone with the news. Facebook was her way of reaching out to people during the crisis, asking for support and prayers.

The death itself wasn’t that much of a surprise. My brother Matt had a long history of drug abuse and threats of suicide. Most news about him was bad news, unless it was that he had checked into rehab again.

A few days earlier, my sister had posted an update about our brother. He had relapsed and used meth again, and was kicked out of the facility he was in at the time. He was paranoid, believing people were after him, and considering harming himself, so he checked into a mental health hospital to be placed on a suicide watch. He was in the hospital on five minute checks, meaning that someone was looking in on him every five minutes to make sure he hadn’t harmed himself.

He managed to hang himself in under five minutes. He wanted to die. There was no hesitation.

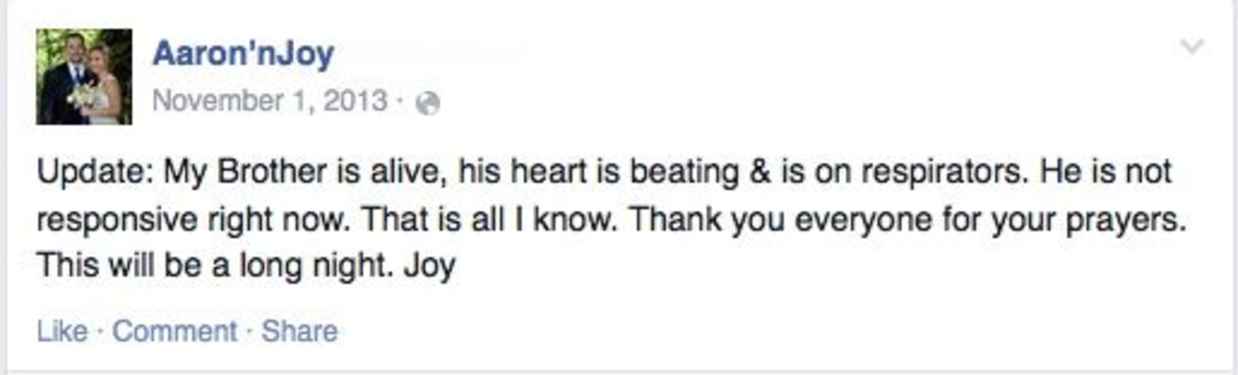

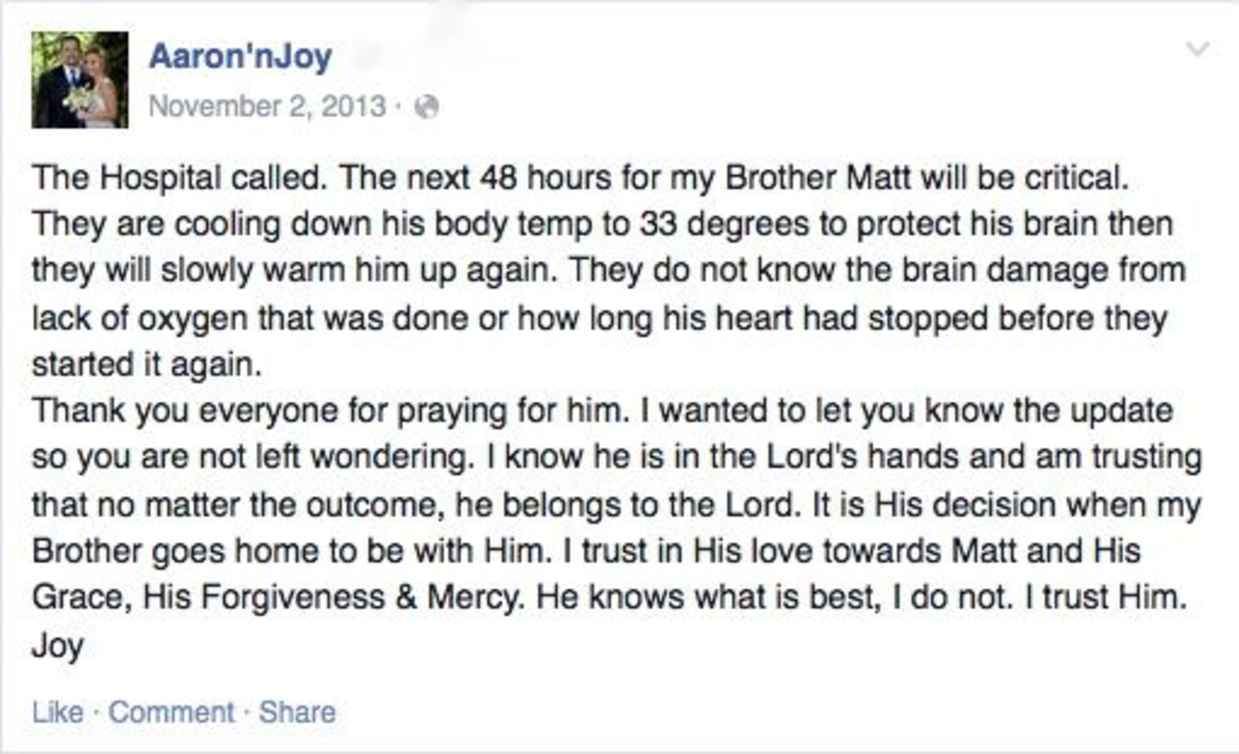

The next few days were a waiting game. My brother had been resuscitated and taken to a hospital where he was placed under medically induced hypothermia to protect his brain for 48 hours, after which he’d be slowly revived to assess the damage. I checked Facebook for updates constantly, staying in my apartment and talking with relatives, waiting for news, trying to come to terms with how I felt about everything. I felt like a ghost watching other people live.

I was literally on the other side of the world and all I could do was check a Web page to see what was happening to my brother. Other people reposted the updates, left comments and prayers, making a virtual memorial to Matt. I felt left out, physically and emotionally. I don’t usually post intimate things about my life on Facebook, and yet one of the most traumatic things to happen to me was unfolding in front of everyone’s computer screen.

After several days of waiting for answers, it became clear that Matt was being kept alive through life support, and that his body was rapidly deteriorating. My family made the decision to remove him from the machines, knowing that he would not want to be kept alive artificially. Then he was gone.

I had spent years living overseas, and I had come to terms with the fact that life back home for friends and family would carry on without me—a stream of baby photos, engagement rings, weddings, breakups, vacations, graduations, fads that were already over before I even heard about them. A funeral hadn’t crossed my mind.

I didn’t make a single post regarding my brother’s death and funeral at the time. Not a single one. I wanted it to be personal, something kept entirely inside myself, untouched by technology. It wasn’t until I returned home later that spring that I truly started to grieve. It was like my time in China put my emotions on pause, and when I returned the full weight of what had happened hit me.

Everything before that had happened online. Facebook was like an anesthetic; I knew that what was happening would cause pain, but I didn’t feel it at the time. I wasn’t there for the funeral, or for the many tear-filled dinners, for hugs, or flowers, or for going through old photos of Matt.

There’s a reason why every culture has a funeral ceremony; we need physical actions to help process our grief. But I didn’t have that for six months after my brother died, so when I did return home, his death hit me hard those first few months back.

My brother doesn’t have a gravestone. His remains were cremated and his ashes scattered into his favorite swimming hole at the Yuba river. There is no place specially reserved for his memory. Except Facebook.

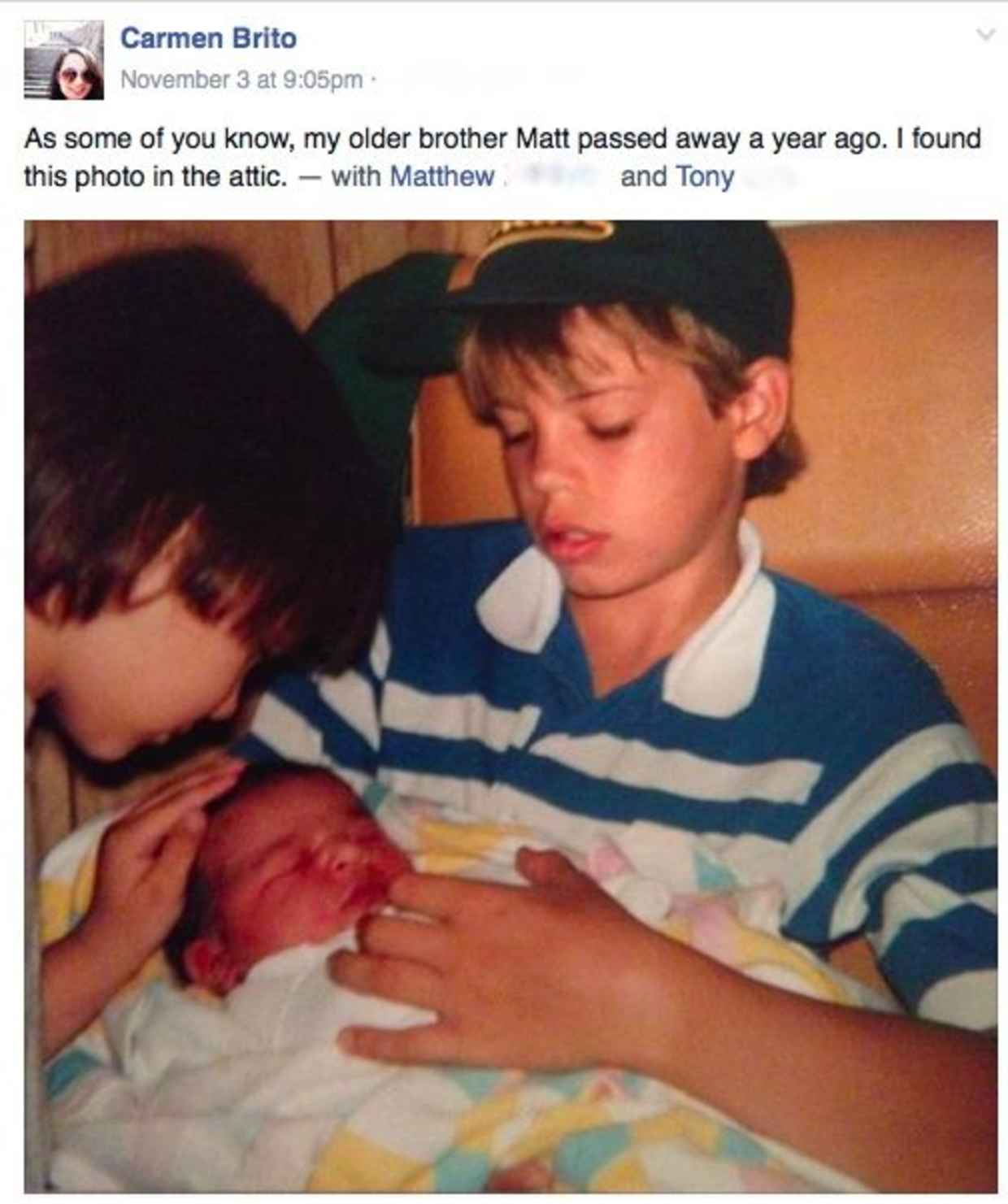

His account is still active, and in the year since his death, every few months someone posts something to his wall. It’s a sucker punch when I see his name come up in my newsfeed.

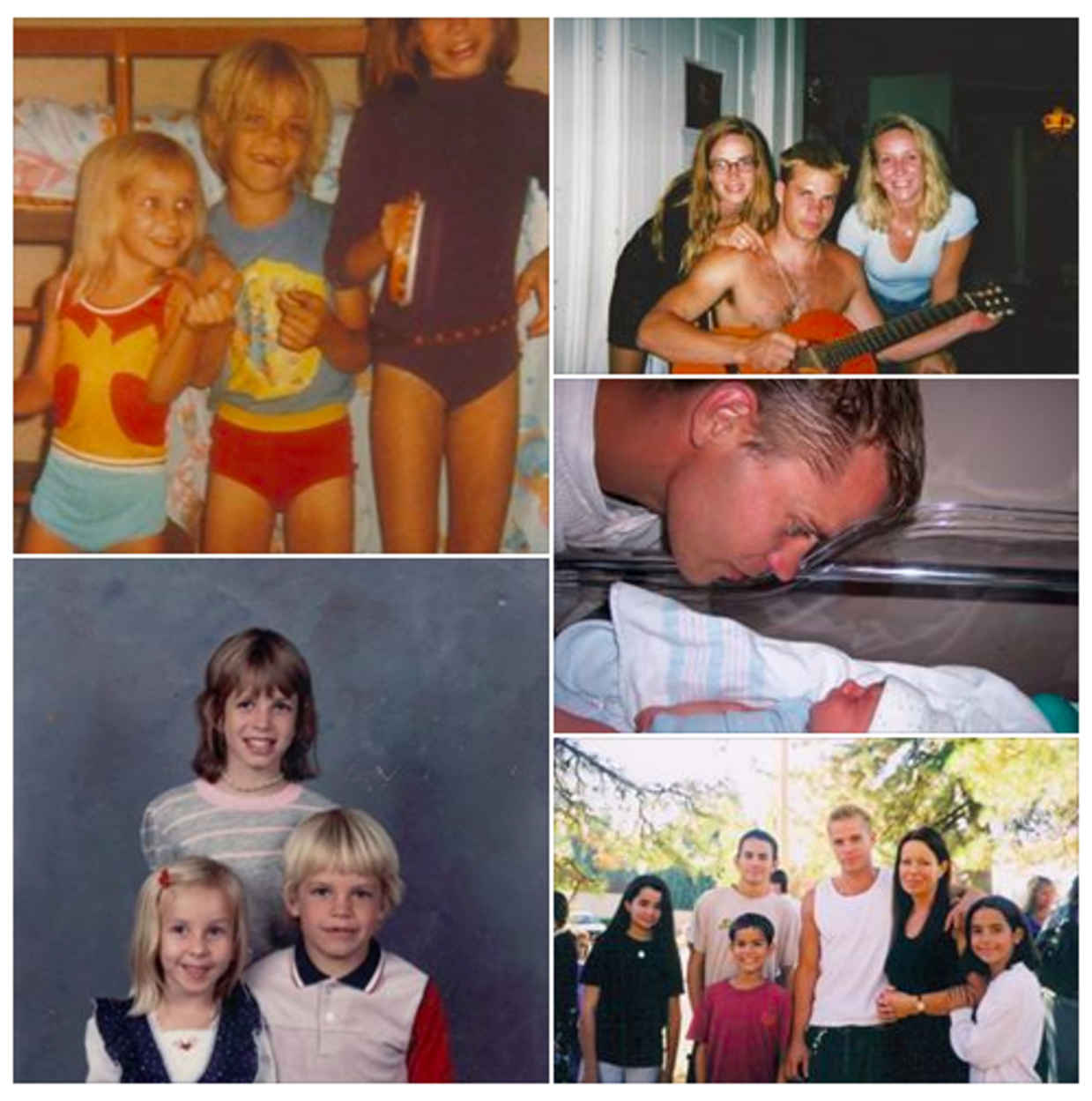

On the anniversary of his death, many people posted to his wall, many childhood photos were uploaded and tagged. Despite the weirdness of tagging a dead person in a photo, it also made it possible for people who knew my brother to reach out to us. Facebook in its own way is a living document, continually growing through messages, events, and photos. A Facebook account for a deceased relative becomes a digital memorial that can be viewed by everyone on their own time.

When you tell someone in person that someone has died, there is an intimacy to that moment that can’t be replicated. It affects you both, and you share that moment exclusively. With social media, death is a mass broadcast. It loses its intimacy, the comfort from telling bad news to a loved one. Yet at the same time it reduces the number of times you have to have a painful conversation.

While my family was waiting in the hospital to take Matt off life support, it would have been too exhausting to personally call everyone that needed to know. A status update saved them from having to repeat terrible news over and over, and instead let them focus on talking to immediate family.

We need our social media accounts in our tech heavy society, but I hope that we don’t forget that certain life experiences can’t exist online in the same way.

There simply isn’t an app for burying a loved one.

This post originally appeared on xoJane, and has been reprinted with permission.

Photo via Mr. Johnson/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)