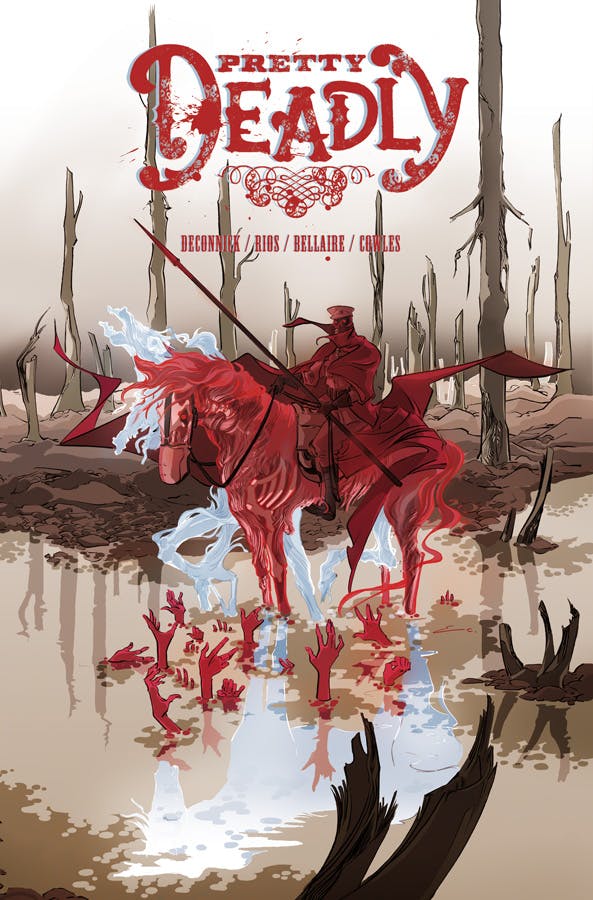

At times, Kelly Sue DeConnick and artist Emma Rios have been accused of making their cult hit indie comic Pretty Deadly “deliberately obtuse” for fans used to their more mainstream fare. But while the hit Western from Image isn’t exactly lowbrow, its mythical characters, gorgeous artwork, and surreal tone have given it plenty of mainstream appeal.

After a dramatic conclusion to the first volume and a long wait for the second, the comic finally returned to shelves this month. We chatted with both creators about the worldbuilding, influences, and ideas that went into their work—and what comics have to do with Stephen Sondheim.

You’ve said in the past that you think that the medium of sequential art is one of the most powerful forms of storytelling, but Pretty Deadly has played with sequencing and temporality a lot. Has it challenged your understanding about what sequential art can do and be?

Emma Rios: When you work with somebody else on a book, the most important matter is how adjust each other’s rhythm for storytelling. Kel and I came to know each other pretty well through working together, through each one’s way of telling the other stories. And I truly think that both of us wanted to be challenged by this book from the beginning, show what we got, and look for ways to impress the other. It really is very exciting.

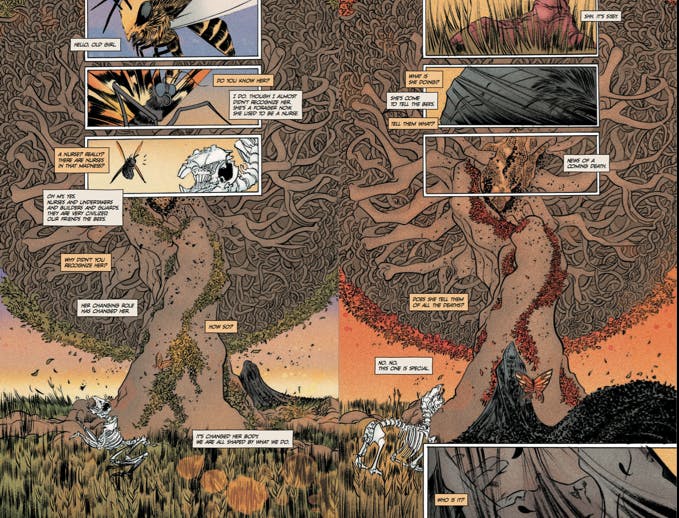

Most of the development of Pretty Deadly happens via email exchanges, scene by scene, and in brainstorming reunions each time we can meet. We never work with finished scripts—neither want to—because this way we can let our stuff retro-feed each other’s better, and even if the beginning was a bit crazy, at this point the scripts are very prose-like and the sound and images blend together more and more smoothly.

In general, the acting and the dialogues are very important to us, especially for knowing how the characters feel every moment, to try to make them characteristic. Sometimes it even feels like roleplaying, kind of, or as if we are just hiding behind a rock stalking them while [they] do their things. Besides, I really need to make the time flow slow—despite the few pages we have per issue and the quantity of information we want to drop on them—and my way to decompress the reading is basically trying to decompose the action by adding panels so you don’t need to figure out what’s really happening in what you are reading and [can] just follow the “frames.”

Maybe this kind of stuff, somehow, gives Pretty Deadly a characteristic pacing that sometimes sets it aside from what we’re most used to in this market.

I think that Pretty Deadly proves just how well comics align with the Western in terms of scope and narrative form. But I feel like Westerns have kind of faded out in the modern comics landscape—why do you think that is?

ER: Well, maybe nowadays people just don’t feel pretty much into historical stuff in general. You still have all those classics—like inherited Band Designée albums, full of references and investigation, but it’s true that now everything is becoming more and more postmodern with made-up worldbuilding, or drunken sci-fi where a ninja can go to Mars and play baseball with an alien octopus. I guess it’s just quicker, fun, and more relaxed to do.

I always feel better out of the extremes though, in general. On one hand, I’m all for recreating believable settings and atmospheres, but I don’t see the point on obsessive historical accuracy if it doesn’t benefit the story to the point of transforming it. And on the other hand my favorite sci-fi stories are those that speak about the same questions we actually struggle with already, aside from worldbuilding.

What is it about Westerns that makes them such a good setting for dealing in mythos?

ER: When I proposed Kelly Sue to do a western I sent her an article about the Surrealism in [Sergio] Leone films.

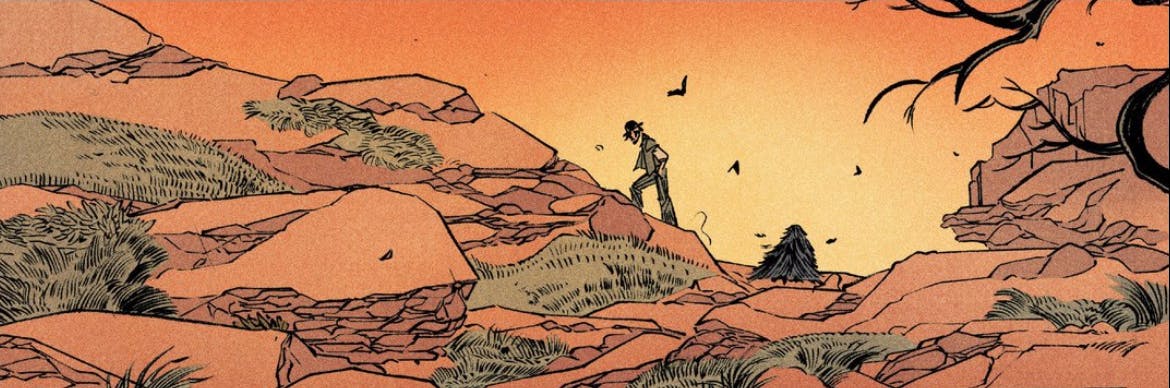

Leone was quite in love with surreal painters like Chirico or Dali, and I think it’s pretty noticeable in his films. Those empty spaces with long shadows or his particular designing of close shots… You can definitely perceive a different world in his films and in most spaghetti Westerns especially.

On the other hand, the heroes of the West are lonely and mysterious. You learn barely anything from them. Basically, they just pass by and only stop briefly to fight against some established order with their particular codes and sense of honor, to solve things, help someone, to take revenge… Like Ulysses in the Odyssey, they feel connected to something bigger, an initiatic journey that changes them and people around, which seems quite an accurate atmosphere for myths.

There are a lot of obvious samurai influences in Pretty Deadly, and also lots of manga influences—the character of Alice, when she appears, looks like a character from Vampire Hunter D dropped into the story by way of CLAMP. Were there any intentional homages to specific Japanese works?

ER: Alice in particular was created from Vampire Hunter D and Klaus Kinski’s crazy character in Sergio Corbucci’s Il Grande Silenzo. But I think it’s the only one who actually has such accurate references. Also, Foxy’s scar was unintentional, but it comes form a really cool character I liked from the old Area 88 comic.

It’s true that I’m crazy for samurai films and sword duels. And that the way I try to develop the mood in the action of Pretty Deadly is totally connected to those classic films from Kurosawa, Inagaki, or Kobayashi and well, with my own experience in fencing as I actually practice myself.

In general, each time anybody draws a sword in the comic I see Toshiro Mifune against Tatsuya Nakadai staring at each other on guard in a field surrounded by silence, or Harvey Keitel against Keith Carradine both exhausted and covered in blood in the last sabre duel in Ridley’s Scott The Duelists.

There are also a lot of obvious comic influences that do what you call the “oneiric” or dreamlike very well—Sandman, Warren Ellis, etc. Were there any specific comics that you looked to for inspiration when you illustrated Pretty Deadly, or were your influences mostly cinematic?

ER: There are two Japanese creators that especially blow my mind these days and whose narratives are a huge influence on me and my work. They are Taiyô Matsumoto and Daisuke Igarashi, and both are really strong creating atmospheres especially when connected to this oneiric feeling you mention. It’s crazy because they can bring overwhelming with very minimalistic proposals, and without even having a regular plot. To mention a couple of books by them that inspired me quite a lot while working on Pretty Deadly, I’m choosing Takemitsu Zamurai and Witches.

Other stuff, comics related, that inspired me was the narrative in Lone Wolf and Cub by Koike and Kojima or Hiroaki Samura’s Blade of Immortal for the action scenes especially, and also Jodorowsky and Boucq’s The Bouncer, Jean Giraud’s Blueberry and Christophe Blain’s Gus as well to recreate the landscapes.

The color scheme is really powerful and important to the narrative—and I think maybe even more so than most comics, because westerns rely so heavily on powerful vistas and saturated landscapes. How closely do you and colorist Jordie Bellaire collaborate in planning those?

ER: Jordie and myself have worked together in a lot of books already, which makes me trust her totally. She is insanely good and always creates something different for each book finding the perfect tone. Moreover when it comes to Pretty Deadly.

In general I think we share a similar vision when it comes to color, always trying to help the narrative beyond any accuracy, making the atmosphere always the priority. And we also have a similar taste when it comes to palettes, saturated colors, etc… So it always feel like she is reading my mind.

I don’t give her any instructions or guide beyond specific things that are important for the script or this kind of vague stuff I was mentioning. I remember talking with her a bit about [David] Fincher and also about the film Le Samourai at the beginning, when we started talking about how to tackle the book and about the possibilities of avoiding the inevitably golden browns and reds. I also share with her the covers when they’re done, where colors are done by me, but always with a “don’t you dare to bet on my two cents” note.

What are some of the most challenging things about drawing the new arc within the context of the “Great War,” as you call it? Is it difficult to retain the Western aesthetic or is it freeing?

ER: Everything is coming up smoothly, and I’m not having any problem mixing both settings in this arc. About France and the war, I’m enjoying a lot the new elements. It’s cool to see Alice and Ginny covered with coats in a landscape full of debris and ruins, and it’s also cool to investigate this crazy war and how people used to live and feel in the trenches. There is a page in which I tried to explain how a trench was designed and use it as a base for the layouts.

Working with soldiers is difficult though, they wear the same uniform and move in groups, you have to be rather careful when it comes to character work.

This war was crazy insane. You have people wielding medieval weapons for fighting in the trenches and advancing with their bayonets against machine guns like in those battlefields during the napoleonic era, and at the same time developing chemical gas bombs and tanks. Nobody was getting the whole picture neither understanding a damn thing of what was happening or about what were they doing. One of the things that worried me the most in this arc was the concept of war and how we were going to deal with it. I really like the way we chose to get rid of the standard epic and how we avoided the topics of heroism inherent to it.

What are you most excited about for the upcoming issues, in terms of plot and character development?

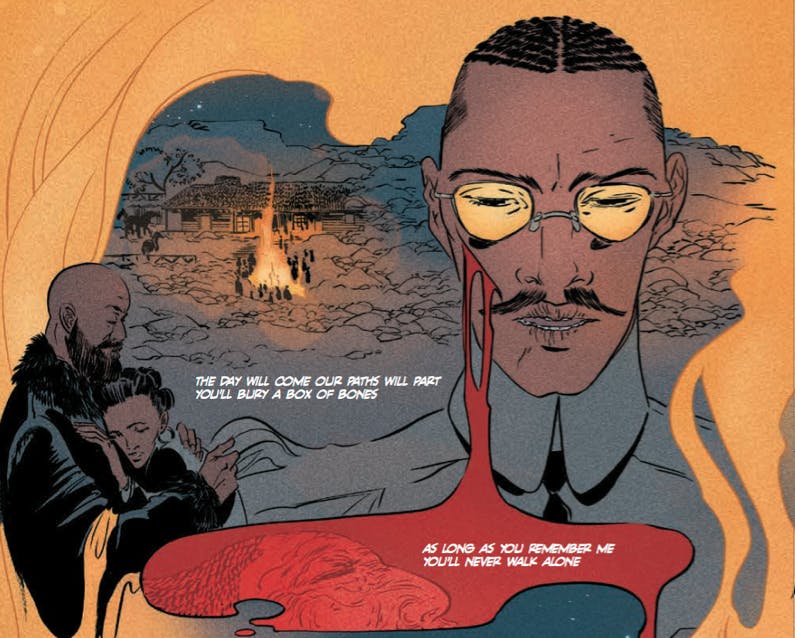

I’m excited about developing the new status quo and see how our characters are affected by it. Having a little girl being the new Death impersonation is hard for everyone. Foxy found some peace and it is noticeable by his looks being more tidy and even a bit younger, but Alice, whose commitment is Cruelty, feels uncomfortable and nervous and looks almost homeless. Sarah is really old now, but still brings the title to the whole arc: The Bear. Moreover, everybody is kinda working in pairs, including Alice and Ginny, which let us expand the character work beyond the former nemesis or parental figures.

We also have several new characters to discover like Cyrus, the small kid that becomes friends with Sissy, and that is our main soldier character here—a cowboy lost in the trenches.

Can you tell us about some of the new characters you’re excited to draw in this arc?

I’m pretty excited about Sarah’s legacy in her family. We have four new characters related to her by blood and each one of them are really promising. Two of them appear in the first arc as the two kids that witness how Alice and her gang burn the house they lived in and beat their mother.

We also have a really weird villain covered with a cloth, and a dead animal reaper.

Having such a long time to craft the second arc of this series—was that freeing or did it create pressure because you knew fans were eager for more?

I try not to think much about it, honestly. Pretty Deadly is always a difficult book that never comes easy. After finishing the first arc, we needed to close things and focus. Kel ended Captain Marvel and started Bitch Planet, I created ID, started editing Island and writing Mirror… all these and the success of Pretty Deadly helped us to adjust to this new status quo of being able to work on creator-owned comics alone. Now we are focused and Pretty Deadly will go on regularly and smoothly until we finish the arcs we have in mind.

You have a Pinterest, and the two of you collaborated on a Pretty Deadly page for it prior to the release. Was that creatively useful for you?

I find this stuff very useful in general, both to communicate and to have stuff available, organized and located. German guns, French guns, Uniforms, French landscape, trenches photos… The Pinterest especially is really inspirational, and each time I’m drawing or doing research, I have it opened on my desktop.

Has your work on Island and 8house influenced the way you create and collaborate on Pretty Deadly?

Definitely. Co-editing Island means that I’m regularly revising other people’s work and discovering new stuff. Working on ID alone myself made me think hard about how differently I work alone than in teams.

And, more than anything, working with Hwei [Lim] on Mirror has been a blast to me as an artist. I work on my own layouts while writing Mirror, and comparing them with her pages is making me think a lot about the way I work and also makes me want to draw better. It’s crazy inspirational.

This was a comic that people were raving about before the first issue. Now that the clamor has settled a bit and people know what they’re getting, has the buzz changed at all for volume 2?

Kelly Sue DeConnick: I try not to notice! It’s a careful balance of needing to do press for the book but not letting myself become too invested in whether someone likes it or not—especially after being asked to explain everything as we go in corporate comics. I had a very good time working in corporate comics and I don’t want to sound derisive of that process, but there was this reaction to being able to do a different kind of storytelling, to stretch our wings, do something a little more immersive that’s a little more challenging. And boy, there are some people who super do not dig that. And on the one hand I’m like, so don’t buy it, don’t yell at me!

I did feel like, it’s more than a couple of people who feel that this is deliberately obtuse, so maybe I need to look at my storytelling, maybe this is something I need to examine. But I don’t want to lose the disorienting feeling of myth space, I don’t want to lose the immersive quality of the book.

I’ve been thinking about [Stephen] Sondheim a lot lately. I love Sondheim, and I’ve been reading and listening to a lot of his thoughts about the creative process, and he talks about simplicity and clarity trumping everything, and I absolutely believe that, but he also talks about how, when he’s writing for the stage, there’s a lot [in the performance] competing with the information that’s given in the song. Comics are not theatre—there’s a very important difference in that the reader controls the page. You can linger on a page of comics as long as you want. You can read and go forward and then move back, you can reread, in one sitting or at your leisure. You can take as much time as you want to take in that story. And so instead of trying to find that balance, I do want to do simple when I can do simple, but I want to use the right word because it’s the right word, and I want to trust the reader to take the time to take the art in because they have it and because they can. I leave it up to the reader to determine how successful that is. I hope we don’t lose any of the magic of the book in that process.

You’ve said that in the second arc you’re trying to write for the issue instead of the trade. Do you think we’ve reached the point in comics that we’ve reached in TV regarding serial narratives?

KSD: You don’t usually have to wait a month for a new episode of a TV show. We ask comic readers to wait a month for a new issue, and honestly, given the time that it takes to put them together, a month is really too fast. You also want to make sure—this is another Sondheim thing—the reader needs to feel like they had a meal. That song is only part of the story, but it needs to feel like a story in itself. That’s a challenge. In a weird way, I think I’m much better at oneshots than longform. So I try to focus on five or six-issue arcs. I have a real fondness for the one-shots because that’s where I do my best storytelling.

Compared to the first arc, where you have a lot of temporal convergence, the second arc has a very clear time jump. What’s the effect of that time jump on the reader?

KSD: Everything about Pretty Deadly is meant to be a little Alice in Wonderland. It’s meant to throw you off-kilter, to keep you a little high. In the world garden, Emma has all but entirely abandoned paneling. That makes it a little more challenging and it’s a little disorienting. I like that. We don’t want it to feel like ‘Ginny walks into a Starbucks.’ It’s meant to be this play with mythology and attempt to answer some big heavy questions for ourselves.

Pretty Deadly relies a lot on frame narratives like the cantares de cego and the “bunny, tell me a story” structure. Does that have a distancing effect on the temporality or the characters? Does it put us in the mindset of receiving a myth?

KSD: When we first started developing this book, Bunny and Butterfly were a whole separate framing structure. Even though there’s a vignette with them that introduces every issue, the big story that encompasses all of the arcs is the story of Bunny and Butterfly. They are inhabitants of the world garden. You see them playing around Sissy now.

In a way, the first volume feels like a prologue wrapped in a prologue. Was it all a prologue building up to where we are now?

KSD: No. We’ve planned four and a half arcs—one is Death, two is War, three is Taxes, three and a half is Love, and four is Hope. These are never official titles or anything, but they’re themes. I joke that Three is Taxes because it’s about price, it’s about cost. They’re each examinations of individual questions. For this second arc, the question is war.

Can you talk a little about Alice and Ginny? I know people are excited to see that relationship evolve.

KSD: The reapers work in pairs. Alice and Ginny are Cruelty and Vengeance, respectively, and those aren’t obvious pairings. You’d think that cruelty would be the darker of the two, but she’s not. Alice is very light in her own way. And Ginny doesn’t let anyone in. You could change her name to Justice.

You’ve said before that you’re not really in Ginny’s head; has that changed, especially considering recent plot developments?

KSD: Not so much. She still is what we planned her to be. She was originally supposed to be Clint Eastwood in a Leone film; she was supposed to be the Man With No Name. And the thing about the Man With No Name is you don’t know where he came from, anything about his family, you don’t understand his allegiances; it always seems like whim. Ginny’s not that. We know about her family. She has a passionate connection to the agenda of vengeance. But there still remains that she doesn’t let you in. She doesn’t talk much at all, she speaks only as much as she has to. That means you have to kind of poke at her to get her to open up.

I’m always seeing your characters compared to Jonah Hex, and I think that’s because that’s the only other comics western people know off the top of their heads. What would you compare it to?

KSD: Sandman, maybe? Maybe that feels like a lofty comparison. It comes with having an alternate mythology. And kind of having that dreamspace—not literal dreamspace as it is in Sandman, but the world garden is a magic place, and we have characters who are products of violence who are born in rivers of blood. It’s very—I’ve seen it described as horror, and I don’t have an objection to that, but I don’t think about it like I’m writing horror or a Western, I think about it as a dark fantasy.

Has starting your own production company changed anything about your creative or collaborative process?

KSD: It got me using index cards a lot more. I spent a week in a TV writers’ room writing an episode of a show that I can’t name yet, and the whole episode of the show was planned out on index cards. And so I learned this way to break out an episode on cards, and so I’ve started doing that for comics. I’m not that good at it! My problem is when I get into the writing I want to tear the whole plan out because I discover so much in the process of dialoguing the scene. When I’m writing them I’m kind of acting them, and very often that means I’ll just change something entirely. You can’t do that in television, because it’s so collaborative, and so many things are riding on each call. But in comics, I can just tear the whole thing up if I want to.

Are there any plans to bring Pretty Deadly to the studio?

KSD: The book is co-owned by Emma and I, so there are a number of people who have interest in it, but we have no particular plans for it right now. And we [DeConnick and Matt Fraction] can only work on one project at a time because we have to keep our books going. And right now we’re working on a project that [the studio] brought up, and we’re having a really wonderful time. I’m really having an unexpectedly wonderful experience in television.

I’m just gonna ask you what your favorite Sondheim musical is.

KSD: My favorite Sondheim! Gosh. I don’t know! You know, probably the three that I think of the most are Sunday in the Park With George, Sweeney Todd, and Passion.

I love Passion!

KSD: You know, I saw Passion in the 10 minutes it was onstage. I saw the original prouction. It was not good, but it was fascinating.

I don’t think it’s a story that’s meant to be ‘good,’ honestly. I think it’s supposed to be ugly and beautiful.

KSD: It’s not—for a story called “Passion,” it’s not. It’s maybe the least passionate Sondheim story there is. It’s a very intellectualized discussion of the nature of love. And that’s just weird and fascinating.

I feel like that’s so Sondheim, though, you know? And it always struck me as really weird because Passion came out the same time as Lloyd Webber’s Aspects of Love, which is also his deconstruction of love and also not good!

KSD: I agree. I was listening to the 538 podcast ‘What’s the Point,’ and it was an episode about how Fandango used their film writing, and they talked about how weird it is to reduce your experience with a piece of art to a number on a scale, and how incredibly subjective that is, to the point of it being fairly useless. And I was thinking, how would I do that? And it wouldn’t be a number. It would be a series of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions, probably. And then one of the questions would be, “Two days later, were you still thinking about it?”

Because that’s so much a part of how I value a cultural experience. Do I take it in and I’m done? Or am I still thinking about it? I saw Passion, in what, 1991? And here we are, 2015, and I still think about that show, even though at the time I wouldn’t have called it good because I didn’t have an emotional reaction to it, I had an intellectual one. And that doesn’t carry as much weight in the theatre. And there are those books that you read that years later you still think about. There are the comics that you read on the toilet, and then there are the comics that you buy in hardback and pour over. If it’s something that I’m still thinking about, then that ups its value for me.

Illustration courtesy Image Comics