The wonder of Elegy for a Dead World is how effectively it teaches players a new type of game that’s more challenging than any punishing first-person shooter or unforgiving platformer.

Elegy for a Dead World is a game about writing, and finding the inspiration to write. For some authors there can be nothing worse than the tyranny of the blank page. Elegy gives its players gorgeous, provocative, and dead alien worlds to explore, using that exploration as a jumping-off point to get the player writing. Elegy then mixes in a veritable writer’s workshop in the form of easy access to other players’ stories.

Writing is play—playing with words, playing with structure, playing with ideas—and Elegy for a Dead World teaches its players how to get started.

Considering the creative void writers often find themselves in at the beginning of a project, it’s appropriate that Elegy for a Dead World begins with the player encased inside a spacesuit, floating in the abyss against a backdrop of colorful nebulae. Nebulae, after all, are clouds of gas that contain within them the potential for brightly-shining stars, just as the mind of the writer (hopefully) contains within it the seeds for a wonderful story.

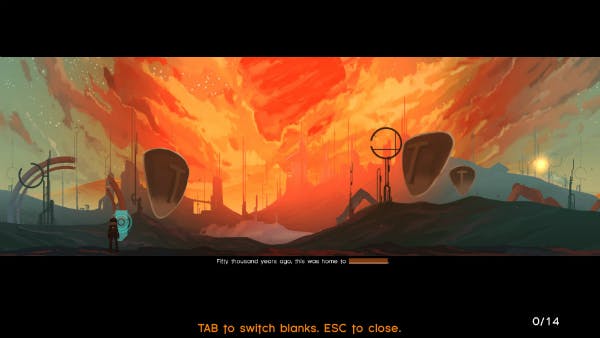

In Elegy for a Dead World, the player is essentially an archeologist visiting planets whose inhabitants are long since gone and combing through the ruins to discover the tale of the people who once lived there. Why did they build what they built? Where did they go? Where did they come from? The ruins on each world are the only clues.

There are several different planets the player can access from space at the beginning of the game. Choosing a world teleports players to the surface, where they can either walk or use their jetpacks to fly through the air and survey the planet. This takes the form of a side-scrolling level design, with buildings or caves the player can exit through darkened doorways.

The aesthetics of each planet in Elegy for a Dead World vary appreciably from one to the next, each giving the player a very different view of the civilization that once lived there. Or the player could view each planet as one step in the evolution of a single race that colonized all the worlds one after the other. Elegy for a Dead World gives the player just enough visual material to inspire their imagination, without stifling their creativity.

Sound plays an important part within each of these dead landscapes, as well. You might encounter what looks like a giant lens that’s filled with light and screeching a high-pitched whine. Is it a machine about to break? A portal into another dimension? Again, the sounds give clues as to the identity of the objects and rooms which produce them, without demanding a single interpretation as to what everything means.

There’s no time limit to each expedition. Players can freely walk left and right across the landscape, entering and exiting rooms as often as they like, and when players decide the adventure is over, they literally fly off into space. There they can choose to explore a different world.

Exploration, then, is half of what defines Elegy for a Dead World. The other, and perhaps greater half of the experience, is chronicling what the player found.

There are prompts along the route of each exploration—white quills at the bottom of the screen—that denote a place the player can pause and open up a journal to make their observations. Elegy for a Dead World provides varying levels of structure at each of these “writing points,” for lack of a better phrase, to assist players in composing their notes.

The player may choose to see a blank page. They can choose to have each writing point present a fill-in-the-blank structure, some of which are fashioned after famous literary works. The writing prompts may also take the form of rhyming couplets. It’s not only the amount of structure provided at these writing prompts, but also the varying types that would make them effective for a wide variety of players.

Players chooses whether or not to compose their writing at these points. There is no point at which the player must write. One could, for example, explore a planet entirely without writing a word, and then go back to the beginning and compose their notes, having a holistic view of the ruins. Players can get to the end of a planet and use the Q and E keys to rapidly cycle backward and forward through the writing points if they want to compose something new, or edit what they already wrote in their journals.

This fluidity is important. Dejobaan Games and Popcannibal, the joint developers of Elegy for a Dead World, could have chosen to make this a straight “A to B to C” experience that, for some players, undoubtedly would have been enough. Ask anyone who’s been at this writing game long enough, however, and they’ll tell you that editing is where as much or more of the work comes in, if the goal is to produce really sharp writing. This is also where Elegy for a Dead World fails to provide any prompts, because it would likely be impossible to do so.

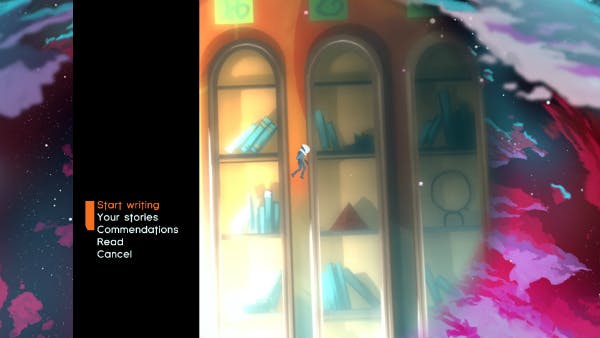

Elegy can only lead the player directly to a first draft. At the end of each planet’s exploration, after the player is finished with whatever edits they want to make, the player can give their story a title, preview what it will look like—the story is told page-by-page against stylized backdrops that pull from the aesthetics of each planet—and then publish the story for other Elegy players to read.

While Elegy for a Dead World can’t provide its players editing tools as formal as the writing prompts, being able to read the work of other Elegy players can certainly provide inspiration for revisions or new ideas to help shape the next story. The ability to immediately read the works composed by other players on precisely the same world is akin to a writer’s workshop, where authors exchange their stories to elicit group feedback.

Elegy player may also Commend the work of other players and search for stories by highest number of Commendations. I see what Dejobaan and Popcannibal were trying to get at here: providing a sort of encouragement for Elegy players to produce their best work. Ranking amateur creative works like this, however, can demotivate as well as motivate.

Popularity is not a metric for quality. Anyone in a creative field ought to know better than to suggest otherwise. And there’s a particular irony in a pair of independent game studios equating popular sentiment to quality work, inasmuch as indie game studios more often than not get the short end of the stick when going toe-to-toe in the marketplace with big-budget games that are immensely more popular (and immensely less innovative) than indie games.

The game interface could be clunky at times. For instance, if I forgot to give a story a Commendation after reading it, the only way I found to guide myself back to the story was to leave a planet, return, skip through all the writing points to get to the end, access the stories written on that world by other players, and then scroll through the list of stories to find the one I meant to give a Commendation to the first time around.

If not for the quality of the stories written by Elegy players, however, I wouldn’t have found myself in that user interface bind so often. I found what read like straight-up archeological records, where players were mostly concerned with cataloging their findings. I read diaries where the writer complained about the supervisor that dispatched them to some dead planet to make notes, and I read more traditional fiction. I may be biased on account of how much I like to read science fiction, but I really enjoyed some of the work written by other players.

The variety and quality of stories written by the community playing Elegy for a Dead World demonstrates the game’s success at enabling its players to write effectively. Writing is so much more difficult than waggling a joystick or pressing buttons, and yet Elegy for a Dead World makes writing accessible to just about anyone who has the heart, and the courage, to try.

Disclosure: Our Steam review copy of Elegy for a Dead World was provided by Dejobann Games and Popcannibal

Screengrab courtesy of Dejobann Games and Popcannibal