If you were hoping for an end to the war in Afghanistan, this was not your week.

Two weeks after the government bombed a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz—killing 22 civilians—reports from the Associated Press found that U.S. military analysts not only knew it was a hospital but were investigating the location as a potential hideout for Taliban operatives. And the very same day, President Obama once again forestalled the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, vowing to keep thousands of troops in the country until 2017 to battle a newly resurgent Taliban.

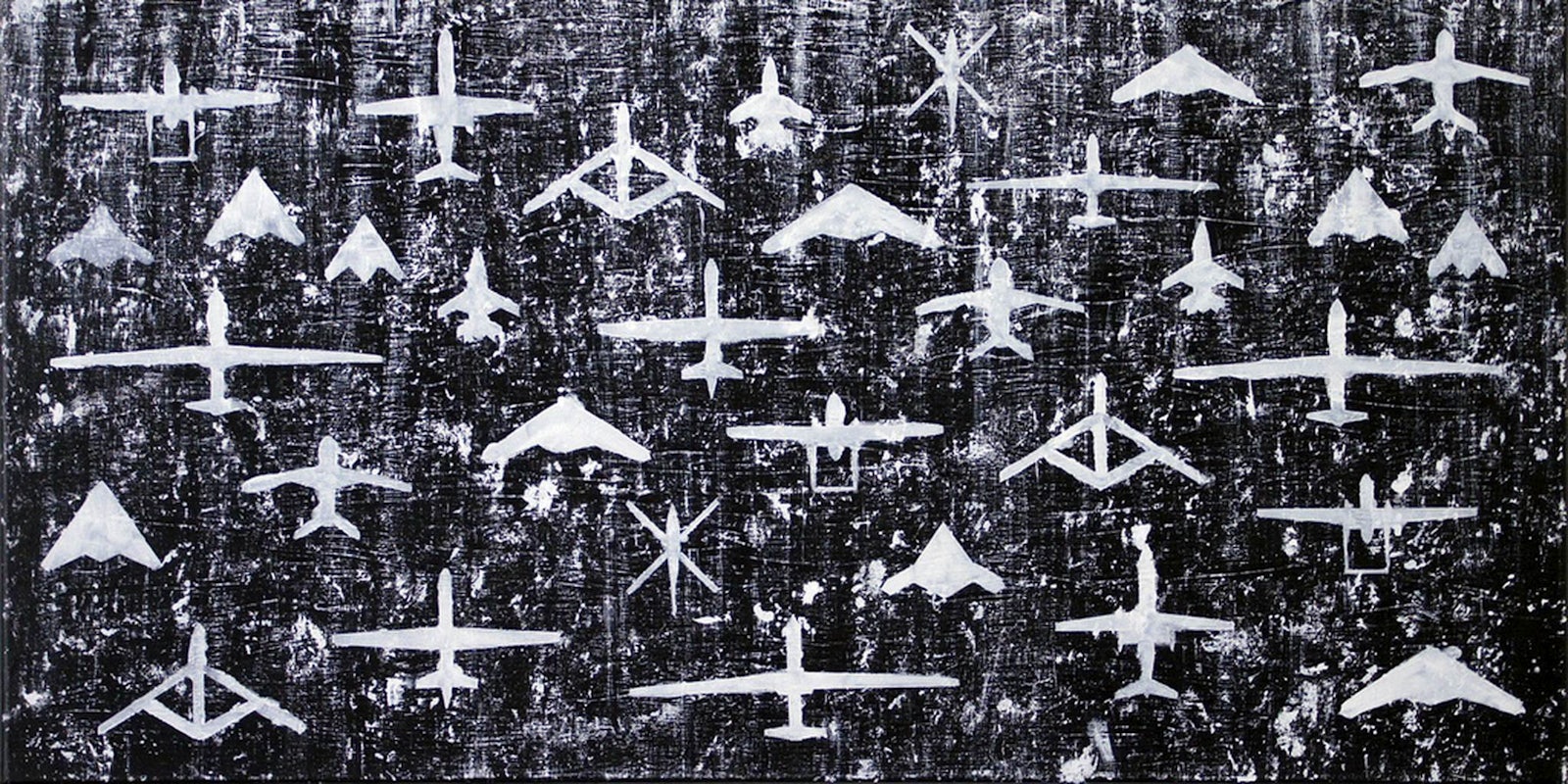

But yet another development is even more startling. The Intercept, the publication started by Glenn Greenwald to host the Snowden leaks, has obtained a new whistleblower in the defense industry who has given the website top secret documents pertaining to the administration’s controversial campaign of drone warfare. The Intercept’s write-up is a damning analysis of the leaks, which detail drone campaigns in Yemen, Somalia, and the Hindu Kush Valley of Afghanistan between 2011 and 2013. Their report finds these campaigns to have been ineffective, imprecise, and immoral.

Although drone warfare supposedly helps the U.S. stay out of armed conflicts, it’s time to recognize that’s not the case. Given the fact that the U.S. is bombing hospitals and promising to stay in the war that leads us to bomb hospitals, the growing evidence shows that drones are keeping us in the Middle East. The drone papers reveal the program to be a loose experiment in warfare, not the surgically precise tool the Defense Department and the Obama administration has sold it as; that unreliability is only making the problem worse.

Their report finds these campaigns to have been ineffective, imprecise, and immoral.

While most of the leaks focus on drone operations in Yemen and Somalia, some of the starkest details are related to the U.S. operations in the Hindu Kush mountains of northeastern Afghanistan, known as Operation Haymaker. A years long program of U.S. Special Forces conducting capture-or-kill raids on Taliban hideouts, Haymaker was one of the deadliest programs for Afghan civilians. “The documents show that during a five-month stretch of the campaign,” writes the Intercept’s Ryan Devereaux, “nearly nine out of 10 people who died in airstrikes were not the Americans’ direct targets.”

That is a startlingly high percentage of unintended civilian deaths, one that’s significantly higher than previous estimates. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a U.K. nonprofit that has been harshly critical of the drone campaign, reported in 2014 that of the 2,400 people killed in U.S. drone strikes since 2009, 273 were civilians. If those figures are accurate, the drone campaign in the Hindu Kush is among the deadliest periods for civilians over the course of the entire campaign.

Such casualties are not favorable in a war against an ideology that recruits on the idea that the U.S.—as well as the West in general—does not value of the lives of local populations. Retired Army General Mike Flynn, who is hardly a peace-loving hippie, said of drone strikes in July: “When you drop a bomb from a drone … you are going to cause more damage than you are going to cause good.” When asked if drone strikes create more terrorists than they kill—by driving hatred of the United States in the region—Flynn added that he “would not disagree” with that assertion.

Many other experts have argued civilian deaths from drone strikes are the perfect recruitment tool for the exact groups we’re fighting. The Atlantic reports that “terrorists and their misguided sympathizers often expose and market civilian casualties—particularly women and children—quite effectively.” And Robert Grenier, former head of the CIA’s counterterrorism program, argued in that because of this, “the unintended consequences of our actions are going to outweigh the intended consequences” in the long term. Our continued use of drone strikes is, thus, not only morally repugnant, but also strategically disadvantageous.

The drone papers reveal the program to be a loose experiment in warfare, not the surgically precise tool the Defense Department and the Obama administration has sold it as; that unreliability is only making the problem worse.

But the inaccuracy of the intelligence and the technology that leads to these civilian deaths is not just a rare mistake from an otherwise healthy military strategy—it’s a key feature. As the Intercept notes, the main reason that civilian death tolls are so high among drone strikes is the Pentagon’s and the CIA’s complete reliance on faulty signals intelligence (SIGINT) to identify targets. Much like the National Security Agency had done with civilian phone records, the Pentagon and the CIA largely chose targets for their drone program by analyzing cell phone metadata and intercepted communications, which the Intercept provides records of in high detail.

According to the anonymous source working with the Intercept, “it’s stunning the number of instances when selectors are misattributed to certain people.” As the source reports, metadata has a less-than-great reputation among intelligence officials, but they continue to use it to find new targets for the drone campaign: “It isn’t until several months or years later that you all of a sudden realize that the entire time you thought you were going after this really hot target, you wind up realizing it was his mother’s phone the whole time.”

Back in April, the American press was shocked at the announcement that an American and an Italian, civilians both, were killed in a drone strike while being held hostage by Al-Qaeda. As the New York Times noted, “Gradually, it has become clear that when operators in Nevada fire missiles into remote tribal territories on the other side of the world, they often do not know who they are killing, but are making an imperfect best guess.”

The consequences of this program stretch beyond the immediate tragedy of the death toll. President Obama’s decision to extend the presence of U.S. troops in Afghanistan until 2017, for example, means the U.S. will expend more money fighting a war the president promised years ago to have ended by now. The Intercept’s report is a fantastic work of journalism that details a moral travesty, one that will and should stain the legacy of this president. But the effects go beyond the specifics of how we define “collateral damage” and, in fact, hurt us more than our enemies ever could.

Gillian Branstetter is a social commentator with a focus on the intersection of technology, security, and politics. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Business Insider, Salon, the Week, and xoJane. She attended Pennsylvania State University. Follow her on Twitter @GillBranstetter.

Photo via jjprojects/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)