BY DOMINICK MAYER

It’s not without good reason that Caroline Kitchens’ recent TIME op-ed titled “It’s Time to End ‘Rape Culture’ Hysteria” has gone mildly viral and caused more than a mild outcry in response. In context of the recent RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) statements to the White House, Kitchens argues that rape is perpetrated by criminals, that “rape culture” as a concept is hazardous to innocent people and that the “feminist blogosphere” is harming instead of helping the larger cause of rape prevention and awareness.

Much was already said, eloquently so, by Zerlina Maxwell in her TIME-published response. (Please follow that link before continuing; her response is excellent.) In addition to counteracting many of Kitchens’ arguments with statistical evidence, Maxwell’s concluding statements resonate.

It’s no surprise that we would refuse to acknowledge that rape and sexual violence is the norm, not the exception. It’s no surprise because most of us would rather believe that the terrible realities we hear about aren’t real or that, at least, we can’t do anything about it. The truth is ugly. But by denying the obvious we continue to allow rapists to go unpunished and leave survivors silenced.

This, it could well be argued, is the heart of the rape culture, the one that’s incredibly real and will continue to be whether or not Kitchens thinks it’s a phantom, some specter looming over decent-minded, law-abiding folks.

It’s also arguably what sustains it.

Setting aside the 60 percent of rape cases that go unreported and more still that are grossly mishandled, let’s go back to RAINN, an organization whose irresponsible task force report for the White House is a deeply unfortunate scar on a generally helpful body of work. Their flippant definition of rape culture as a “buzzword” is highly questionable when in the same document they acknowledge, on the very first page, that “one out of every six women and one out of every 33 men are victims of sexual assault — 20 million Americans in all.”

The report goes onto explain that “those of college age are more likely to be victimized than any other age group.” These are not they simply the figures of an overwhelming, malevolent criminal population.

However, they serve as yet another representation of the gulf between the understanding of rape as a daily epidemic and its reputation as an act conducted in shadows. The latter is the too-common idea that rapists are boogeymen, sinister creatures in clown costumes or wilting pedophiles. They’re the sort of unbelievable (in the literal sense) monsters that show up to kidnap young girls in the second acts of bad action movies until Liam Neeson or whoever shows up to violently destroy them.

But that’s not how it works. They’re rarely so obvious. Young men and women aren’t just getting caught in alleyways late in the evening, and as great a fantasy as it might be, there aren’t gruff heroes kicking in the door on every single person who decided that another human being’s body belonged more to them.

The rapists are the people we know, and that’s precisely why the monsters exist. We create works of fiction because that’s what we can understand — because it’s what helps people with the cognitive dissonance of having to look at a significant other, at a family member, at a friend as a real monster, the kind that doesn’t understand that no means no and that if yes becomes no later on it’s still no, not an invitation for pressure and coercion.

The rapists about which Kitchens writes are always somebody else, always a vague figure that exists in the world but not in our world, not somebody that we or anybody we care about would ever encounter. The scariest part about those rapists is that to argue this is to argue that rapists will be somebody else’s problem, that they do exist but not at your front door. Just somebody else’s.

And this is where rape culture comes in. It’s what keeps you believing that rape is an inevitable part of the human experience, that it is something other than a matter of people attempting to claim other human beings that they usually know personally as their own. That rape is not unlike a car crash or somebody falling onto train tracks in that it’s something that just happens sometimes, and it’s unfortunate but it just does. It’s what convinces so many young men and women that it was their fault, that they shouldn’t have had the audacity to get drunk in public or wear a piece of clothing they liked or go for a walk or leave their front doors in the morning if they didn’t want this to happen.

Because here’s the thing about monsters: when you create them, it means that their victims are part of the fairy tale too. The people who these monsters attack are no more real than the monsters themselves.

This is a chance to change the way we talk about that.

Rapists are monstrous indeed, but they aren’t monsters. They’re people you know. You’ve probably walked by at least one of them on the street at some point in your life. And their victims are just people. You don’t have to know them to feel for them, to fear for how many of them have been victimized, to work toward a better world in which it happens to fewer people and the ones to whom it does feel comfortable coming forward about it without being told by TIME that their suffering happened in a vacuum.

Rape culture, as Maxwell notes, is very real. It’s what churns out the tales of monsters, and it’s what gives them a real face. This won’t stop atrocious things from happening to innocent people overnight, but it’s one facet of a great many that can ensure that we one day live in a world where rape is seen for the criminal and ethical act of horror that it indisputably is.

Dominick Suzanne-Mayer is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association and a film critic and co-managing editor at HEAVEmedia. He also hosts Permanent Records, a Chicago open-mic dedicated to dramatic readings and/or told stories of everyone’s embarrassing youthful years.

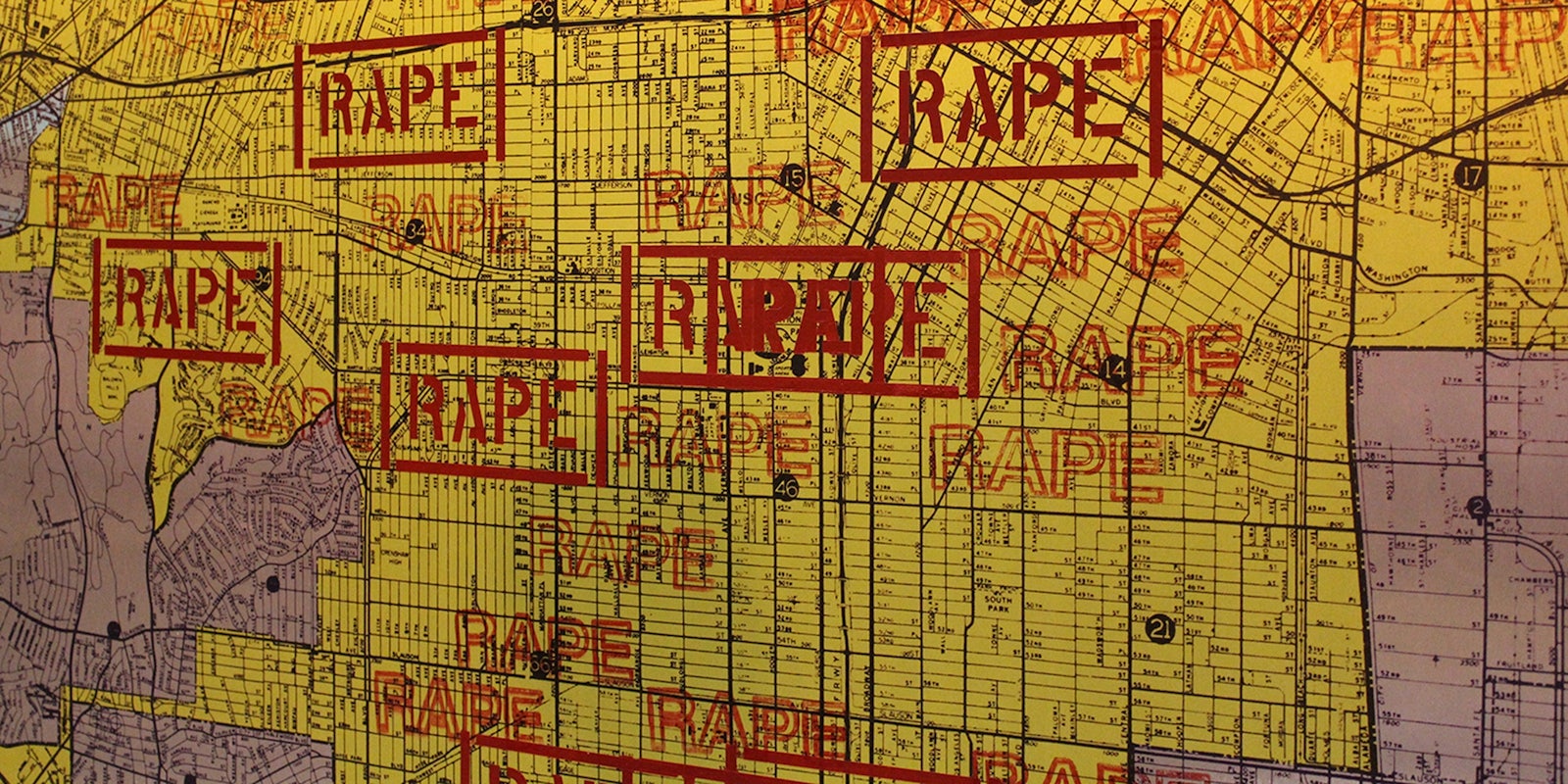

Photo by Neon Tommy (CC BY-SA 2.0)