When I saw that Beverly Johnson was trending on Twitter today, I clicked her name immediately. Johnson was the first black woman to appear on the cover of Vogue, in their August 1974 issue, and like any child of the eighties, to me, she represents glamour and sophistication. I adore her. When I saw that the news was a Vanity Fair piece in which Johnson accuses Bill Cosby of drugging her, my first thought was, “No. Not Beverly Johnson.”

Another tweet echoed my sentiments. It said something along the lines of: “Bill Cosby drugged Beverly Johnson? Now he’s gone too far.”

Yet last month when another former supermodel, Janice Dickinson, accused Cosby of drugging and raping her, reactions ranged from wondering aloud if the accusation was true to publicly denouncing her for seeking publicity from tragedy.

I suspect those reactions are because Dickinson is loud an inappropriate. She’s had extensive plastic surgery and speaks openly about her past drug abuse and sexual escapades. Even her accusation was brash and theatrical. Unlike Johnson’s polished, beautifully written piece in Vanity Fair, Dickinson accused Cosby on television tabloid Entertainment Tonight in front of a camera with a full face of makeup and her speech halted with lots of “ums” and “uhs.” When CNN reported the story, they did so to old footage of Dickinson preening on a red carpet at an US Weekly event, flirting with photographers. Dickinson is an inelegant, inarticulate rape victim, and no one likes that.

But why do we need to like a woman to believe her?

In the past month, 25 women have come forward accusing Bill Cosby—our Bill Cosby, Cliff Huxtable, host of Kids Say the Darndest Things—of brutally sexually assaulting them. But critics might say those were wannabe actresses or no-name groupies or washed-up models with a history of substance abuse. The voice it took for a sea change in public opinion was from a woman with a reputation no less sterling than Cosby’s once was: a household face, a successful businesswoman, and a close, personal friend of Oprah.

We love her just as we loved him, so now we’re finally willing to admit that our trust in Cosby may have been mistaken.

Beverly Johnson’s story perfectly matches Janice Dickinson’s account, along with the two dozen other women who have come forward to accuse him perfectly. She respected Cosby, who was a big star at the time, and he acted paternally interested in her career right up to the moment he drugged her. Then Johnson’s story veers in an unexpected way: She called him a “motherfucker” and resisted his attack until he put her in a cab and sent her home.

And I like Beverly Johnson even more for that. It takes a brassy, strong woman to look her would-be rapist in the eye and say, “You motherfucker. How could you do this to me?” Many of the other women didn’t do that, and the public distrusts them for it. Don Lemon, host of CNN Tonight, even went as far as to scold one woman, “There are ways not to perform oral sex,” as if she chose to be raped and the oral rape itself was no more important than holding on to a piece of old gum.

But every woman’s story should be taken seriously when it comes to rape. What other crime would take two-dozen accusers before we considered the fact that the man who committed them was a criminal.

Imagine a woman walks into a police station and says, “That man stole my car in 1980.” The police might laugh and say there’s nothing they can do about a 34-year-old car. But imagine that another woman comes in behind her and says, “He stole my car in 1981” then another comes in and reports that he stole her car a week later. How many women would have to go into that police station before they started watching that man as a car thief? No officer would sit before a room full of women and say, “Are you sure you didn’t just lend him the car and forget about it for three decades?” No one on the Internet would comment, “Look at all these bitches, just trying to get free cars.”

But we have to trust a woman’s entire character before we can believe that a man has had sex with her against her will. Look at “Jackie,” the anonymous rape victim from the Rolling Stone story that’s come under fire in the past few weeks for errors in reporting. Since we don’t know Jackie, it’s hard for us to say what did or didn’t happen to her. Sure, she says she was raped, but the public sentiment seems to be that since we can’t see her for ourselves, it’s better to err on the side of skepticism. Even Rolling Stone says that they “misplaced trust” by believing a rape survivor.

Why doesn’t that skepticism work both ways? If Jackie could be a liar, then it stands to reason that the men she speaks of in the article could be rapists. Jackie’s friends speak to changes in behavior; they say that she told them she was sexually assaulted and became so withdrawn that she stopped going to classes. Some would rather believe that all those people are liars rather than say that several men might be rapists.

In Cosby’s case, it’s nearly 30 to 1 at this point, but the only voice many people will listen to comes from a woman they think they know and love.

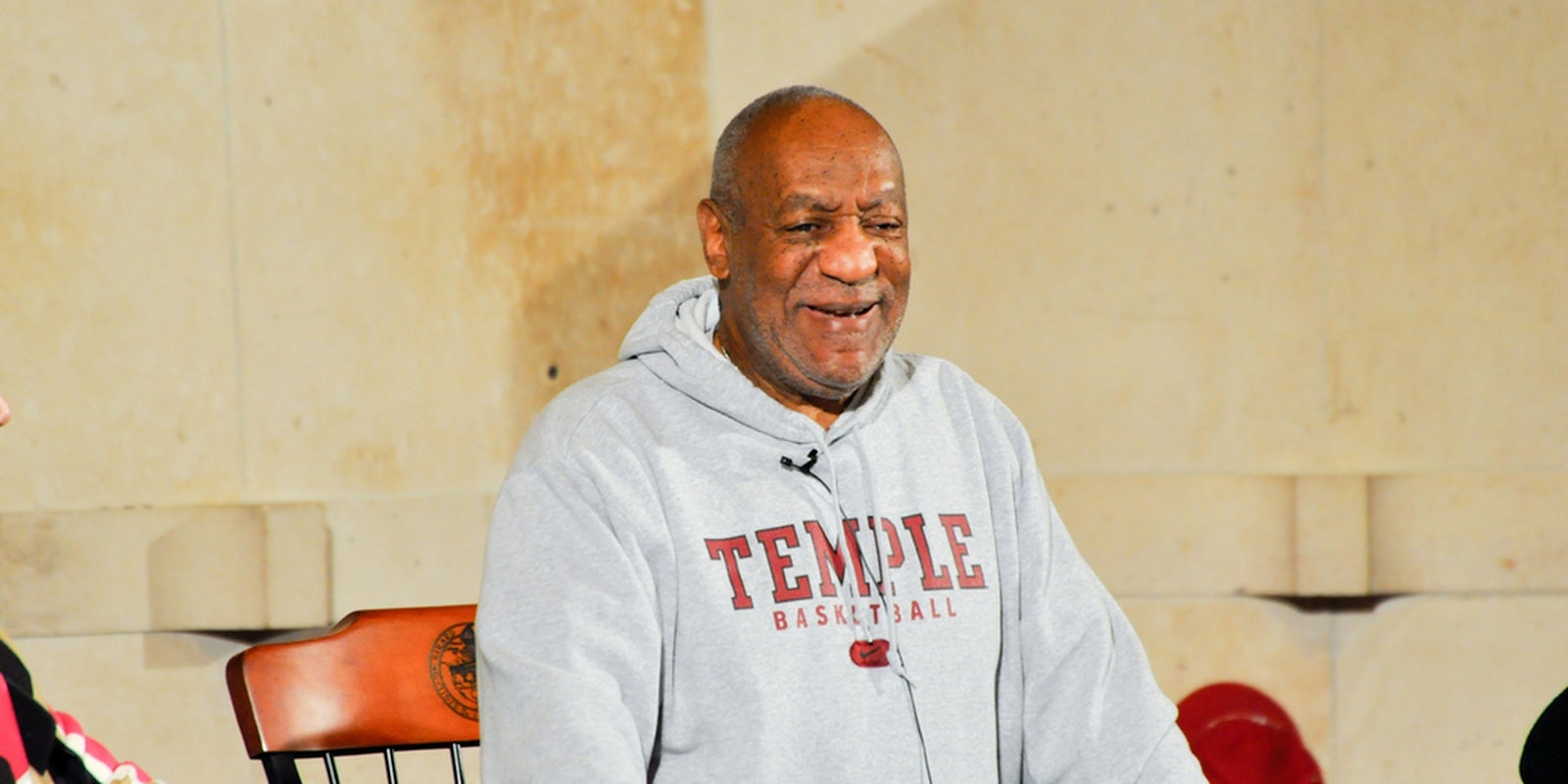

Photo via World Affairs Court of Philadelphia/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)