Patrick Stump, Pete Wentz, and the other members of the band Fall Out Boy may have returned from their hiatus this week in order to Save Rock and Roll (or so their newly announced album attests), but they’re still listed on charts worldwide as “pop” music.

Their fans, however, know their niche and stick to it. Say what you will about bandom, but whatever you do, don’t call it popslash!

Bandom, you say? Isn’t that just a fandom for bands? Not exactly. Depending on who you ask, bandom either means just “band fandom,” or it refers very specifically to the online fandom for a particular group of bands who toured together frequently in the mid-2000s and whose members past and present formed interconnections. At the center of this circle are three bands: My Chemical Romance, Panic! at the Disco, and Fall Out Boy. Also included in the community are a number of outlying bands like Cobra Starship, the Like, and All American Rejects.

You might have heard explosions from members of bandom all over your Tumblr dashboard this week—first a bona fide fan scandal coming out of My Chemical Romance fandom, and then the news that Fall Out Boy is putting out a new album after nearly five years on hiatus.

Bandom is a specific community among many in the vibrant subculture of fanfic-based fandom known as RPF, or Real Person Fiction. But it gets hard to categorize fandoms about real people. Unlike fictional characters, they often overlap. This complexity has previously made it difficult to figure out just which bands are part of the narrower use of “bandom.”

Attempts to define where the community begins and ends usually focus on the indie labels who originally connected the bands, particularly Fall Out Boy’s original label, Fueled by Ramen (FBR), and the label they’re currently on, Wentz’s Decaydance. Decaydance started as an FBR imprint before expanding into Wentz’s own label, so several FBR bands also fall under the Decaydance umbrella—including Panic!, the Cab, and All Time Low. But not all “bandom” bands fall under the label umbrella—My Chemical Romance was never signed to either Decaydence or FBR.

So what is the real connecting thread that joins these bands? Probably Pete Wentz himself. In fact, the fandom is often nicknamed “Six Degrees of Pete Wentz.”

But real people, of course, form new friendships all the time, and Pete Wentz really gets around.

The difficulty of pinning down which bands and personalities count as part of FBR “bandom” is probably why people who just like bands a lot take issue with the word being used so narrowly. Although members of the FBR-based fanbase have fought to own the term “bandom” locally, other band fandoms have resented the idea that the label doesn’t apply to them.

What makes things even trickier is that names for band fandom have been around as long as music fandoms have existed. At any given time, someone might consider themselves a member of bandom, popslash, and/or bandslash fandoms. Depending on who you’re talking to, all of these things might be interchangeable examples of Music RPF—but most likely, they’re considered separate and distinct fandoms with their own histories, cultures, and languages.

So what do you need to know to have a coherent conversation with your band-loving friends? Here are the basics.

Bandom (a.k.a. bandslash)

To be safe, only use these terms when you’re talking about the online fandom for Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy, and My Chemical Romance. If you want to really speak the language, refer to the “FBR bands”—the group of bands organized loosely around the Fueled by Ramen record label, which is still associated with Fall Out Boy although they are no longer on the label.

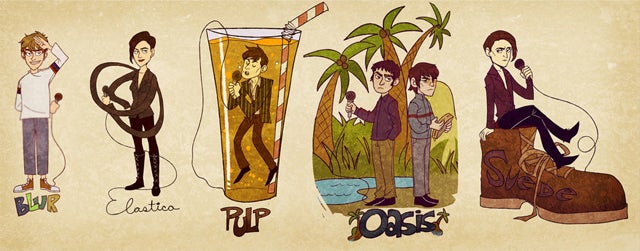

Illustration by ivybeth/DeviantArt

This can technically be used to describe anything from Beatles fandom to One Direction, but most often, “popslash” refers to the slash (fanfiction about male-male encounters) fandom around N*SYNC and the Backstreet Boys, and the various members therein.

This is another complex term for a number of overlapping bands, most notably a group of indie British bands in the late ’90s—particularly Blur, Suede, Pulp, Manic Street Preachers, and Oasis. Their successors, like Franz Ferdinand and the Killers, sometimes get labeled “Britpop,” along with other current British pop bands, but when in doubt, stick to Blur.

Illustration by nadiezda/Deviantart

Fandom armies

Okay, so they’re not armies, exactly (and Rihanna fans are “Navygirls”), but nothing says fandom like a massive amount of people who identify as “little monsters,” “Directioners,” “Beliebers,” and more. Technically these labels are different from the others on this list because they explicitly describe the fans themselves, not the bands or pop artists they like—but knowing the most common labels for the most common pop fanbases is a good way to quickly identify what your friends are talking about.

Geographic divisions

Often fans are drawn to the culture around music as much as to the music itself. It’s convenient to group different “flavors” of music by their countries of origin. In fact, if anything, these labels can be somewhat restrictive. For example, Japan alone claims the broader genres of J-pop, J-rock, Visual Kei, and J-rap among its endless distinct genres and subgenres of music—there’s even “oyaji rock,” or “old geezer rock” for the fandom for J-rock bands of yore. Nonetheless, here’s the alphabetical breakdown of some of the most commonly used abbreviations for regional band cultures:

C-pop: “Chinese pop.” This moniker refers to old and new breakthroughs in Chinese pop music, with subgenres including “Mandopop” (Mandarin pop) and Tai (Taiwanese) pop. Popular examples include the renowned girl group S.H.E and one half of the wildly popular transnational group Exo.

Europop: “European pop.” If you’ve ever watched Eurovision, you’ve already got the basics.

J-pop: “Japanese pop.” As Japan expanded its exporting of Japanese pop culture throughout the ’90s and 2000s, fans around the world discovered Japanese rock bands like the Pillows and the emerging massive studio culture that churned out pop groups like Morning Musume and Tackey and Tsubasa. In addition, artists like Utada Hikaru and Ayumi Hamasaki, as well as pop-rock bands like Asian Kung Fu Generation, Porno Graffiti, and Malice Mizer became familiar to Western audiences through having their music used for anime theme songs. Each of these artists became commonly roped into the collective label of “J-pop.” By the time Korean pop culture began to overshadow Japan’s in the late 2000s, millions of fans around the world were already listening to Japanese artists on a routine basis.

K-pop: “Korean pop.” Having recently captured the attention of the world with “Gangnam Style,” the Korean wave, or “Hallyu,” has been on the rise since the mid-2000s with the explosion of popular bands like Super Junior, DBSK, and Girls’ Generation.

T-pop: “Thai pop,” not to be confused with Tai-pop, or Taiwanese pop. Phleng Thai sakol, or international Thai music, originally described the blending of classical Western music with traditional Thai music, evolving over the years into an amalgam of musical influences. Today Thai pop is an emerging cultural movement with many popular bands coming from Thai labels like Kamikaze.

Though members of fandom are very specific about their terminology, pop music is constantly expanding and crossing borders in genres as well as cultures. With it, the idea of bandom continues to evolve and expand as well.

Though for lovers of Fall Out Boy, “bandom” will probably always refer to the community of fans who are joyously celebrating the band’s return this month.

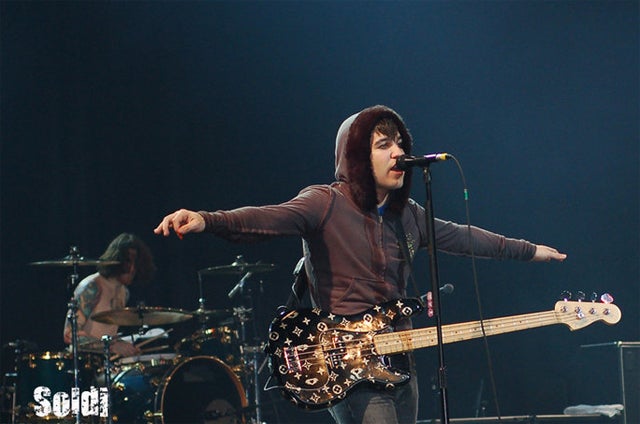

Photo by artiste-inconnue/DeviantArt