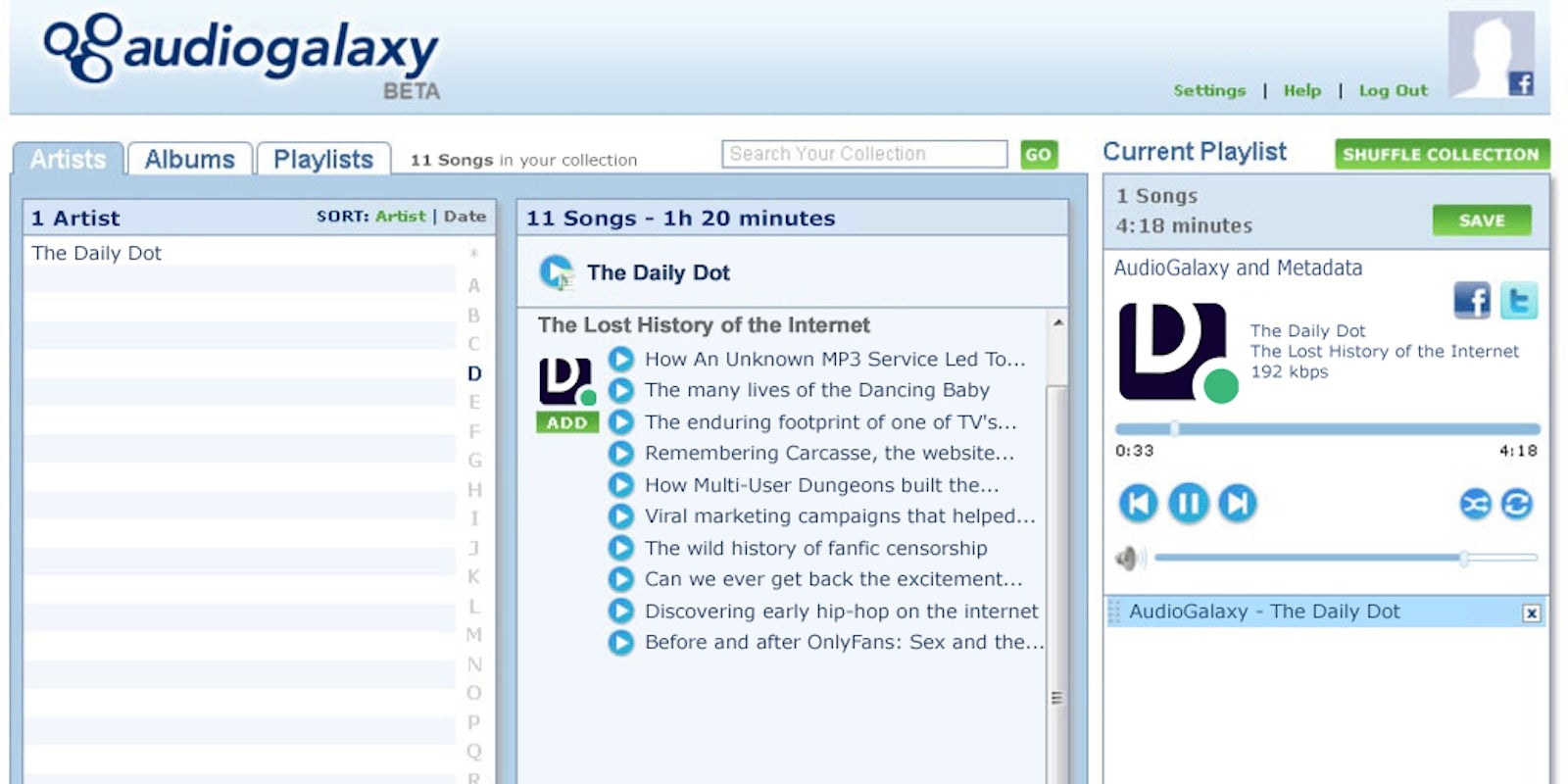

2002 was a pretty good year for the internet. Google released the Google Search Appliance, the company’s first piece of hardware, AOL integrated ICQ into AIM, and perennial teen faves My Chemical Romance released their first album, I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, among other things. However, 2002 was also the year the website Audiogalaxy shut down after four years in the Wild West of MP3 file sharing.

Most people remember the big hitters of file sharing: Napster, KaZaa, The Pirate Bay. Maybe their weapons of choice were SoulSeek, Limewire, OiNK’s Pink Palace, or just scraping MediaFire. Whatever it was, the early aughts had a different relationship to file-sharing than the internet of now. Among all these big names and faceless P2P engines, Audiogalaxy stood out as a unique fixture in the space.

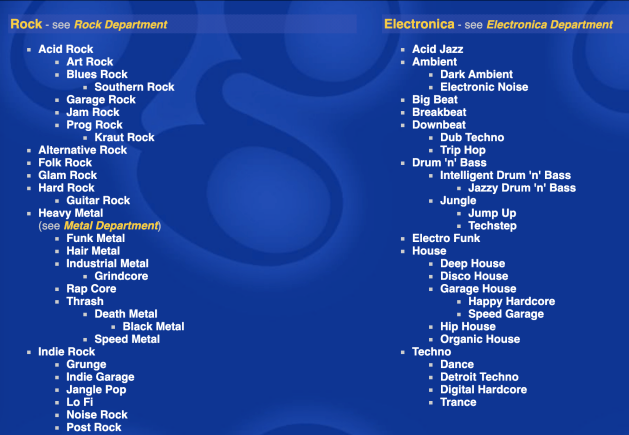

In 2019, NPR called Audiogalaxy the “digital wild west’s best outlaw record store,” and that’s what it felt like. Dark blue and deeply linked, like many of the social media networks that would come after, Audiogalaxy boasted itself to have the web’s best music search. It was user-friendly and built with interconnections in mind, with taxonomies and hierarchies that Wikipedia would go on to make commonplace on the internet. Neatly categorized and extremely clickable, Audiogalaxy was like walking into a local record store, ready to pick and choose whatever felt right to you, without the judgment of any of the employees.

I don’t remember how I came across Audiogalaxy. At 13, I was no stranger to Napster and KaZaa, and I downloaded enough spam and malware to have a little bit of a handle on what I could get away with. I got my first home computer in 1998 when I was in the sixth grade. We had walled-garden AOL and I, somehow, was allowed to use the internet more easily than trying to hang out with my friends IRL. I started email zines, wrote terrible fanfiction, and roleplayed as a sparkly blue dragon (Sorry, Mom). Maybe it was a combination of my early internet days with growing up in New Jersey and its beating heart of pop-punk down the entire length of the Turnpike that led me to my own emo dreams. With my Weezer-inspired thick black glasses, I ended up on Audiogalaxy looking up a little band from Kansas called The Get Up Kids and my whole life changed.

“My Apology” was never my favorite Get Up Kids song, but it’s the first one I remember hearing. There was something about the guitar riffs and lyrical hooks that caught my ear. I found my way to the album it was on, 1999’s Something To Write Home About, and ended up finding it on Audiogalaxy. Many clicks later, I made it to the Emo hub where there were pages upon pages of bands I could dig into, with “also try” notes under all of them. My teenage quest for knowledge and being the coolest kid I knew was satisfied in a way I still have trouble describing—looking at these pages now still brings back a visceral reaction for me, a desire to dive in and read every word on these pages.

Former staff critic and current frontman of Okkervil River, Will Robinson Sheff told the Austin Chronicle in 2003: “I felt like if we were going to be giving music away for free, we should be trying to get people to experience the world of independent, cool music outside of the same old crap they hear on the radio.” These highly curated, hyper niche experiences allowed users at the time to open their hearts and ears to music from basements around the world. It was like the cool older siblings I never had, a place to explore and understand myself without anyone asking why I cared. It was just there for anyone to browse and choose what they wanted, an internet full of a different kind of serendipity than the algorithm-driven kinds we have now.

I remember spending my after-school hours poring over the pages and connections, building a mind palace of relationships between bands and labels. Invested in the details of any band in the genre from the petty discourse between the lines of Taking Back Sunday and Brand New lyrics to the various bands that James Dewees would be in. I was proud to know every detail about the rosters of Drive-Thru, Vagrant, and Saddle Creek, record labels full of bands from states I had never been to, with a handful I was lucky enough to catch at New Jersey institutions like the Birch Hill and Club Krome.

Almost a full twenty years later, the internet is a completely different place. Try explaining Star Wars Kid to someone under 25, and they can’t picture an internet without YouTube. Waiting three hours to download one song? Preposterous when Spotify and Apple Music are in your pocket. As an information professional, I spend so much of my time thinking about how lucky kids are that they have worlds of information available to them so quickly. I think a lot about how the internet affects our brains, makes us who we are when we’re too young to realize it.

These foundations of attempting to know everything about Midwestern ‘00s emo set me on a path that would eventually bring me to another Wild West of internet categorization. With my Vagrant Records MP3s by my side, I got my Masters in Library and Information Science, doing a thesis in metadata usage on the then two-year-old social network Tumblr. Another dark blue, deeply linked website without an algorithm, I was drawn to Tumblr for its pop-punk and emo communities. I made lifelong friends on the platform through sharing MP3s I probably got off Audiogalaxy and developed a passion for understanding what brings people together and how they talk about these things.

I put this knowledge into action at Know Your Meme and eventually made it home to Tumblr in 2013, after my first boss told HR she’d been looking for a unicorn librarian. Deeply embedded equally in information science and fandom, I used my years of Audiogalaxy research and knowledge to help build a deeply human-curated taxonomy exclusive to Tumblr. Through analyzing millions of tags in Tumblr’s annual Year in Review from 2013-2020, launching Fandometrics in 2015, and a myriad of other internal projects, the Tumblr taxonomy was one of my biggest feats. It was built with love, with the desire to be a place to help people connect out of their own desires, not ones algorithms are choosing for them. It was important to bring different corners of the platform into the light so more people could find them, the way I found the niche music genres that filled up my heart so many years before.

I left Tumblr in early 2021 to open up my internet again—to give myself a way to bring my research to the whole internet instead of just one platform. With the work I’m doing now, I spend a lot of my time thinking about Gen Z. Digital natives who were given the internet on a silver platter. The research done, the kinks worked out, the new paths paved for them to glide down. But what’s been sacrificed is that heart of human curation—when it comes to opening new doors, algorithms lead so much of the conversation, letting computers define what you see and what you find instead of what your heart leads your fingers to click on. And yes, while algorithms are built and coded by humans, they’re made without the nuance of the human brain. While the algorithm can learn the tags and topics of the interests you have from the most broad to the hyper-niche, it can’t tell what you feel about them. Human curation gives the algorithms a superpower—a depth of emotional intelligence.

I think a lot about my own knowledge seeking and dedication to understanding how things are interconnected, and how Audiogalaxy’s user interface and human-curated recommendations set my brain patterns up for a deeper understanding of music connections. I wonder how the algorithms of today will challenge people to think outside of our current boxes, how people will challenge the norm of algorithms and find a way to bring the serendipitous spirit of the old internet back. Until then, I’ll be here spinning my Get Up Kids records, building more taxonomies.