This week, the master and commander of online retail embarked upon a different era of conquest.

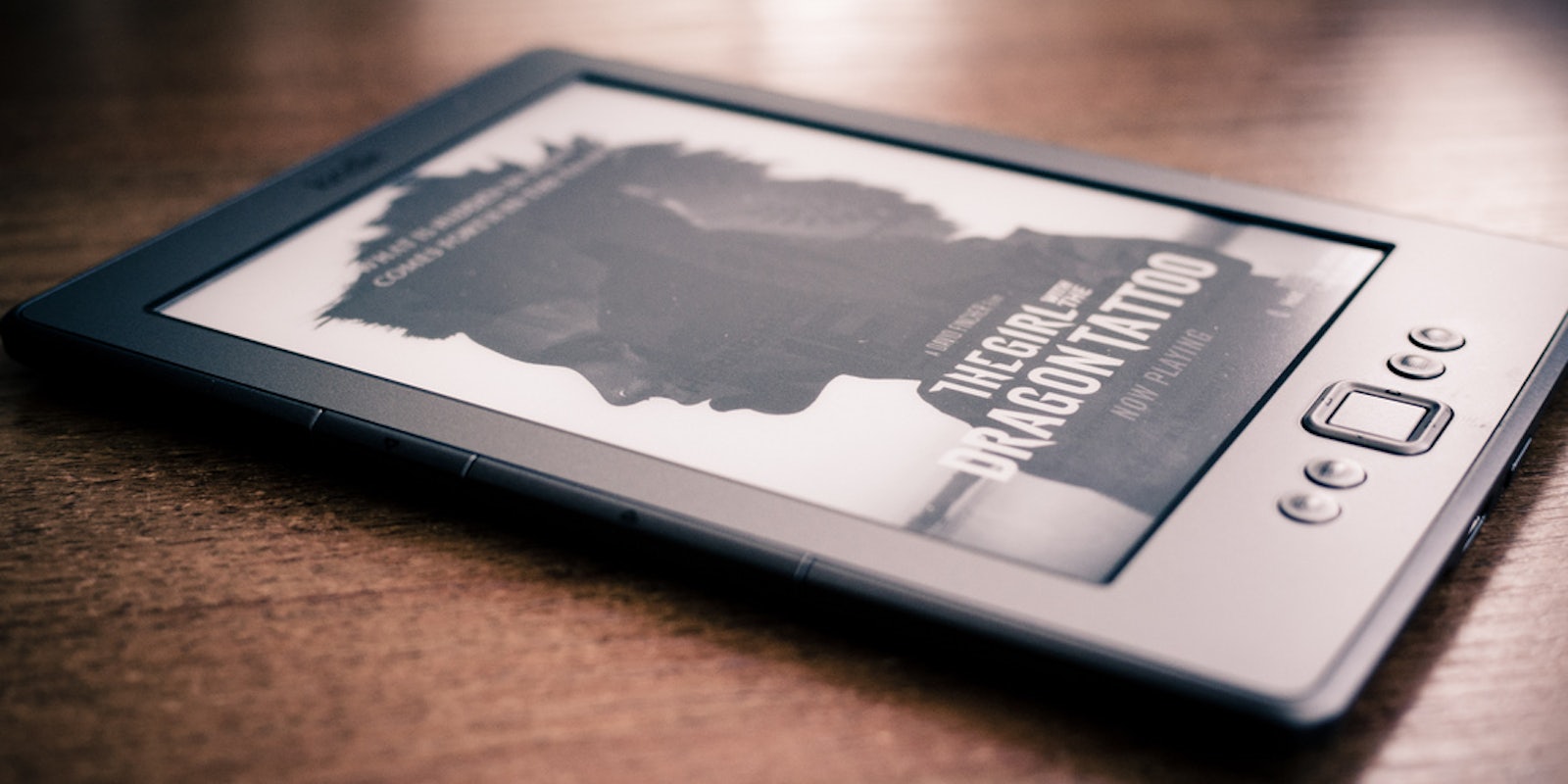

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, is opening up a physical bookstore in the University Village neighborhood of Seattle. Amazon Books, as the store is called, will offer bestsellers and staff recommendations, as well as tailored suggestions based on the online shopping habits of the company’s 244 million active customers. Speaking to the Seattle Times, Jennifer Cast, the Vice President of Books at Amazon, described the philosophy of the store as “data with heart.” While the store will sell Amazon technology (including Kindle e-readers and Fire TV streaming dongles), Cast says, “Our goal is to do a great job selling lots of books.”

Speaking to the Seattle Times, Jennifer Cast, the Vice President of Books at Amazon, described the philosophy of the store as “data with heart.”

While a physical Amazon location could pose a direct threat to independent bookstores—an industry Amazon has all but decimated—it also serves the purpose of giving Amazon a more human face at a time the company needs it most. The last several years of the company’s 21-year history have been some of its most successful—as well as its most turbulent. While revenue has soared since 2010 (climbing up from $34.2 billion all the way to $89 billion in 2014), the company has found itself mired in criticisms of its effect on workers, publishers, and consumer culture as a whole.

Big tech companies like Google, Facebook, and Apple have become famous for the perks and comfortable environments they foster. Tours of their headquarters are more likely to see Guitar Hero stations and nap pods than endless mazes of cubicles. Amazon, meanwhile, is most often associated with the torturous environments of its fulfillment centers, in which tens of thousands of employees work tirelessly to fulfill the impossible standards of data-managed shipping schedules. This summer, the New York Times published a scathing report detailing the pressures put on Amazon’s white-collar workers, who were actively encouraged to spy on one another and often found illness and family came in second to the bottom line.

In the midst of those public controversies, Amazon has waged several high-profile battles against book publishers over the last few years. The company’s impressive control over the book-buying world means CEO Jeff Bezos has been able to set the tone on disputes over pricing and the evolution of e-books. This leverage was first displayed in 2010, when Amazon responded to a joint attempt by Macmillan and Apple to raise the standard price of e-books (from $9.99 to $15) by pulling all Macmillan books and products.

While several other feuds were settled before such drastic measures were taken, last year’s all-out brawl with publisher Hachette—in which Amazon delayed the shipping of Hachette books from authors like John Green and Stephen Colbert—found many questioning the value of Amazon to the literary world. In an essay for the New Yorker, George Packer wrote:

In the influential, self-conscious world of people who care about reading, Amazon’s unparalleled power generates endless discussion, along with paranoia, resentment, confusion, and yearning. … To many book professionals, Amazon is a ruthless predator. The company claims to want a more literate world—and it came along when the book world was in distress, offering a vital new source of sales. But then it started asking a lot of personal questions, and it created dependency and harshly exploited its leverage; eventually, the book world realized that Amazon had its house keys and its bank-account number, and wondered if that had been the intention all along.

Publishing isn’t the only industry affected by Amazon’s often tyrannical power. Last month, the company announced it would stop selling streaming devices from other manufacturers, including Google’s Chromecast devices and the Apple TV. The Verge’s Tim Carmody aptly described the maneuver as a “multi-front platform cold war”—in which tech companies attempt to best each other “while grudgingly granting and denying access to each other’s products and services depending on the deals and strategic advantage available.” Unlike Google and Apple, however, Amazon has outsize influence over huge sections of the retail market, not just consumer electronics.

This combination of emotionless labor relations and calculated corporate control over books—and seemingly any other consumer product—is why a physical bookstore makes so much sense. Amazon, as it exists in most people’s lives, is a magical and illusory service in which you can literally push a button to make stuff arrive at your door. The combination of this ubiquity and its corporate culture, however, may make Amazon less associated with the techno-optimism of its Silicon Valley brethren and more with unavoidability of a store like Walmart (or, perhaps most presciently, Buy ‘N Large).

To avoid that fate, the company has taken real-world steps to stop itself from becoming a soulless Internet superstore. Just this week, Amazon joined most other major tech companies by expanding its parental leave policy to 20 weeks—up from six—as well as a “leave share program,” in which an employee can exchange their own leave for salary lost by a sick spouse or family member. While that’s certainly a welcome change for Amazon employees, it’s also a small step for the company in developing a workplace as modern as its technology.

Unlike Google and Apple, however, Amazon has outsize influence over huge sections of the retail market, not just consumer electronics.

While not as substantial as the progressive policies offered by its competitors, an Amazon bookstore is a necessary attempt of making Amazon feel literally like a breezy, enjoyable trip to the corner store. For one, this movie recognizes that people genuinely love shopping. According to the latest edition of the AT Kearney Omnichannel Shopping Preferences Study, which interviews 2,500 shoppers from a myriad of demographics, found an astonishing 90 percent of consumers prefer brick-and-mortar stores over online retailers. This is because retail stores enable consumers to attach a personal identity to a company, rather than the faceless glow of a computer screen.

An Amazon competitor that has found this especially true is Apple. The Apple Store is a key aspect of the company’s identity, reinforcing its products as fashionable, high-tech, and (most of all) user-friendly. A new location in Brussels, for example, was personally designed by Johnny Ive, the Chief Design Officer of Apple, to merge the consumer world of the iPhone and iPad with the high-end fashion world offered by the most expensive models of the Apple Watch. Microsoft began opening its own retail stores in 2009, described by Gizmodo’s Wilson Rothman as “an awful lot like an Apple Store, albeit one with Surface tables, Xboxes and more employee t-shirt colors.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xLTNfIaL5YI

Such stores give consumers the chance to personally interact with the products a company is selling. Touching and experiencing them before they make the decision to swipe their credit cards not only makes them more likely to buy something in the first place—it creates a link between brand and consumer.

It’s a connection Amazon has struggled to make as it grows larger and more omnipresent. The power held by Amazon, combined with its troubled work environment, makes the company too easy to see as dystopian. The most connection consumers feel with Amazon is their web page and a happy cardboard box, which is little comfort when headlines make the company seem terrible. While Amazon might be able to change that association with smiling cashiers, it is still a long way from changing the culture that creates that image in the first place.

Gillian Branstetter is a social commentator with a focus on the intersection of technology, security, and politics. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, Business Insider, Salon, the Week, and xoJane. She attended Pennsylvania State University. Follow her on Twitter @GillBranstetter.

Photo via Sergey Galyonkin/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)