By CHRIS R. ALBON

America’s diplomats are reportedly considering new rules for social media. According to a draft version of a US State Department document, the new proposed social media policy for government employees would impose a two-day review period for tweets and a five-day review period for blog posts. In case it isn’t apparent, this would constitute an enormous shift in how the government relates to social media.

Reacting to the news, Will McCants argued this week in Foreign Policy that the review period will undermine America’s ability to interact with and understand foreign citizens. This prompted Alec J. Ross of the Office of the Secretary of State to clarify that the review periods are a maximum, and that the new rules would in fact make the State Department faster and more open. Even if that is the intention—and I have no reason to think that it is not—it will still be a loss for the Internet. Why? Because it means the sanitization of one more area of the Net.

The relationship between technological progress and politics is governed by one fundamental fact: when technology breaks new ground, politics will inevitably follow. Technology is in an eternal race with politics, but the former is always slightly ahead of the latter. When technological advancements occur, there is a lag between their popularization and their politicalization. It takes politics time to catch up; but it always does. The beauty of this race is that gap before the catch up. Before politics plants its flag, we get to experience a domain unsettled by traditional policies and laws. We get the Wild West.

Twitter is no exception. Government agencies have been on Twitter for years, but much of that time has been spent without significant guidelines for how they should use the medium. The result has been a wonderful diversity and ingenuity in government Twitter behavior.

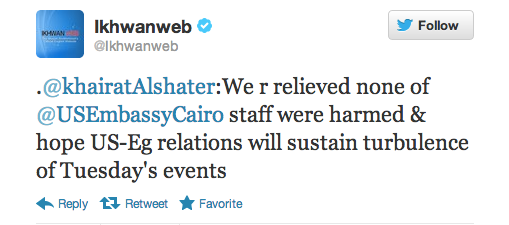

Take the Twitter accounts of US embassies. Each embassy has its own Twitter account, and they evolved in very different ways. On September 11, 2012, violent protests erupted against the US embassy in Cairo sparked by an anti-Islam film made by a group in the United States. Two days later, the official Twitter account of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, an Egyptian political organization which with the US has a historically tense relationship, tweeted this to the US Embassy’s Twitter account:

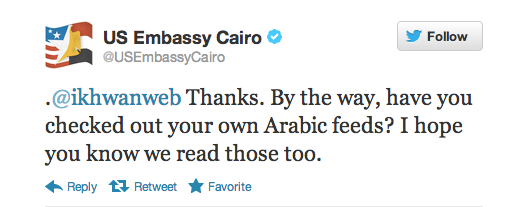

The message was a cheap attempt at feigning concern by the Muslim Brotherhood, whose Arabic language Twitter account had been simultaneous sending tweets that were seen by many as encouraging the protesters. How did America’s diplomats on Twitter respond? Snark.

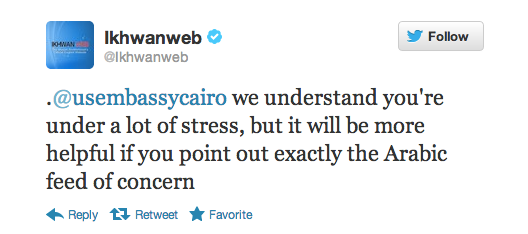

Yes, while protests were occurring outside the walls of their compound, the official Twitter account for the US embassy in Egypt was digitally slapping one of the country’s most influential political organizations. And of course, the Muslim Brotherhood fired right back:

This type of informality is almost unheard of in traditional State Department communications, but as Max Fisher points out, it was par for the course for @USEmbassyCairo.

The embassy’s Twitter behavior was a creative and effective method of getting people engaged with the diplomat’s mission. During the tiff with the Muslim Brotherhood, I followed @USEmbassyCairo—despite having never been to Egypt. @USEmbassyCairo followed right back.

Without formalized rules of behavior, Twitter as a medium for US government communication has an air of informality and realism. You feel like you have a relationship with the Twitter account, even if you do not know who the person behind it is. I am not naive enough to believe that social media behavior could ever have escaped regulation. It was inevitable. In fact, the State Department should be commended for attempting to create—relative to traditional rules for government communication—what are actually very progressive rules for social media. But still, we will lose something. The very act of formalizing social media behavior, however well intentioned, destroys the best part of social media. My disappointment with the State Department’s new social media policies is not about them being bad rules; it is that there are rules at all.

Chris R. Albon is a political scientist and writer on the global politics of science and technology. Presently, Chris leads the Governance Project at FrontlineSMS. Prior to FrontlineSMS, Chris earned a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of California, Davis.

Photograph by Geoff Livingston