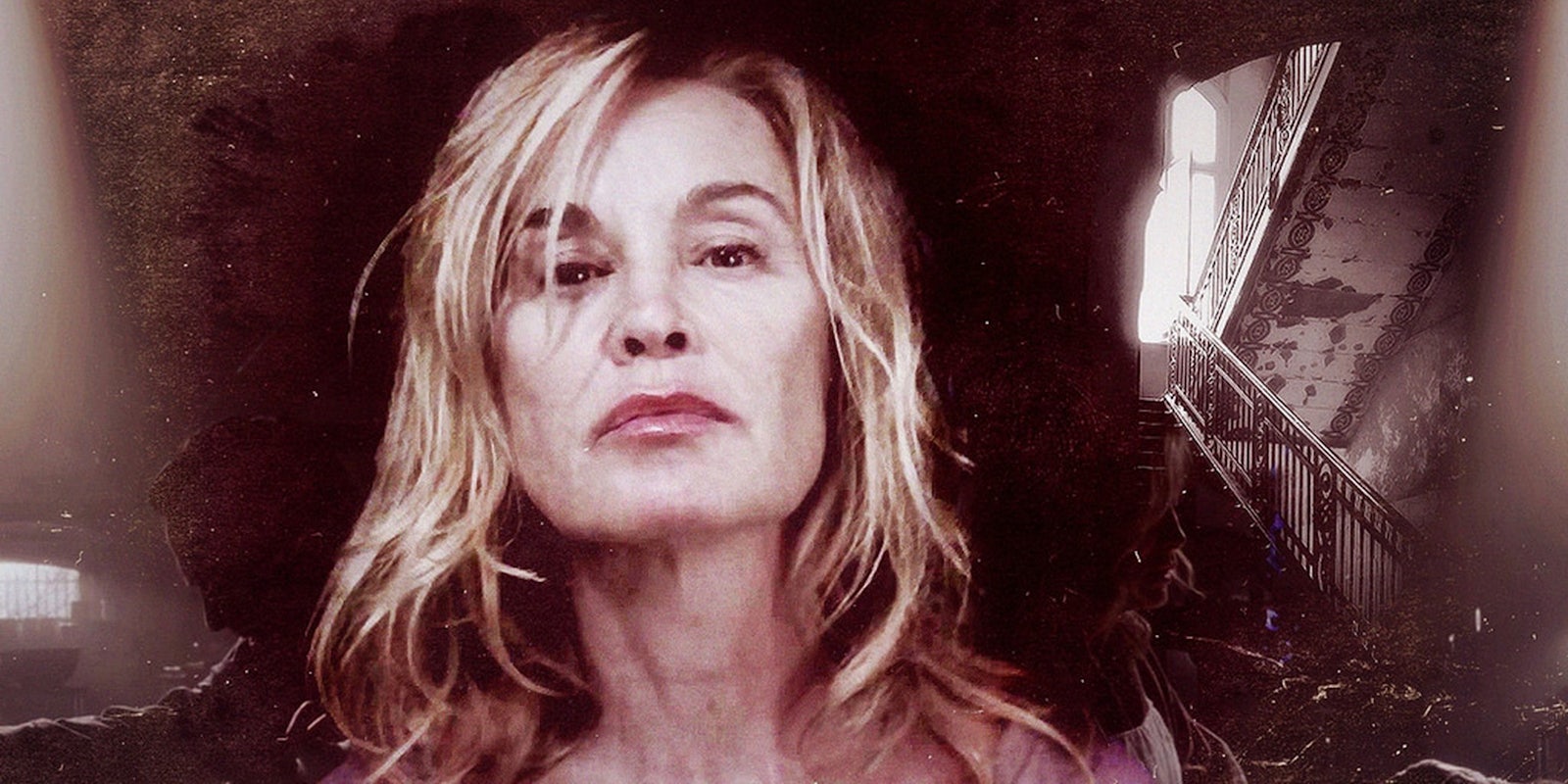

This December, American Horror Story fans got an early holiday present, when Coven debuted on Netflix. For those dissatisfied with the show’s fourth installment, Freak Show, currently airing on FX, it’s an opportunity to revisit what was the most-watched season to date. Fondly remembering the snarky banter, decadent New Orleans landscape, and weird appearances by Stevie Nicks, I interrupted my binge watch of J.J. Abrams cult-hit Fringe to return to the Coven pilot, “Bitchcraft.” What I found was that the switch between Fringe’s plot, which trades in scientific experiments that expand the scope of the human body, and Coven’s presentation of a “witch” for contemporary audiences, came almost too easily. Teasing out the connections between science and magic seemed crucial to understanding what made Coven, among the other American Horror Story seasons, a critical success.

Characters in Fringe frequently cite science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke’s law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” while in “Bitchcraft,” witchcraft is scripted as a “genetic affliction.” That these two randomly selected dramas—and several more besides—explain magic through a technological apparatus, is not surprising. As far back as 1942, Star Wars Episode V: The Emperor Strikes Back screenwriter Leigh Brackett wrote: “Witchcraft to the ignorant…[is] simple science to the learned.” Still, in an age where the delineation between artifice and artificial intelligence is ever-harder to determine, we have to ask ourselves: Why do we continue produce mythologies of magic in a technological age?

As the wearable tech market expands with offerings like Google Glass, iWatch, and FitBit, our consumer culture poses questions of how might we better know our bodies, extend our physical capacities, and augment our lifestyles towards an ostensibly “good” life—that mythic ideal to which we culturally aspire. This commitment towards a “good” life isn’t measured just in purchase of discrete objects, either. Our fantasies of better bodies lead us to invest in film franchises, like the Bourne series or Marvel’s The Avengers, in which engineered superheroes gross over $1.5 billion per movie, or stories of cognitive expansion such as Lucy, Luc Besson’s 2014 sci-fi thriller.

What I think struck a chord with audiences in Coven (and what is perhaps discordant for viewers of Freak Show) is that Coven scripted characters that share the same concern for better bodies as the average viewer. One could argue Ryan Murphy’s televisual career is primarily based on aesthetics of difference, yet Coven is the only show to normalize physical aspiration for an ideal self. Within the show, magical powers are added like software updates—telekinesis, divination, power negation, transmutation, and the many other abilities presented—and eagerly sought after in an attempt to be “The Supreme,” the most powerful and able-bodied witch in the coven. More importantly, however, Coven presents a more democratic fantasy of self-enhancement. The women don’t need extra capital or social status to augment their own bodies, they just need their innate biological ability.

If this sounds like it smacks of biological determinism, or possibly neo-eugenicism, well, it’s not too far off. Unlike fantasies of technology, which often give us narrative arcs about social utopia, Coven’s fantasy of magic is a response to the crisis of bodily decay. At a cultural moment in which our right to death with dignity or have an abortion, to say nothing of the gross systemic devaluation of black lives, is a topic of national debate, a magical world presumably gives us temporary relief—a medicinal shot of escapism to entertain us and help us cope with the pressures of our societal concerns. Instead, what I see happening is a type of cruel optimism, or as Lauren Berlant puts it, “a kind of relation in which one depends on objects that block the very thriving that motivates our attachment in the first place.”

This theme is already played out in countless sci-fi novels, television shows, and films: We crave and create better technology that will better our lives, but the end result is that the technology we thought would give us what we wanted is the unraveling of that selfsame dream. It’s the central conflict for everything from Alien or the child-oriented Smart House’s twisted riffs on the technological “Mother,” to Star Trek: Into Darkness’ extended meditation on the hierarchical value of life: that which we think we want is what prevents us from having what we really want. Perhaps a failure—or at least the reason we’re saturated with dystopian films—of the sci-fi genre is that by locating the object of desire as a tech-thing outside of our bodies, it is easier to narratively identify “what went wrong.”

Magic, or witchcraft, internalizes this conflict, making it easier to rationalize ethically gray decisions and more difficult to assign blame. The choices in Coven, however bad they may be, are relatable on the level of biological security; given the choice of life or death, the show challenges viewers to ask what they wouldn’t do to stay alive. Coven’s magic, then, is the most ability-oriented fantasy imaginable: the evasion of death. Therefore, the witch’s drive towards power is also towards a curative able-bodiedness. A better body, self-sustaining without the need for technological enhancements. Magic is its prosthesis.

Where does this leave us? Searching for a way to narrate a good life, through the best means we know. As consumers existing in a precarious public sphere, we imagine better futures, and different ways of being. When sci-fi’s technological advances become an inaccurate reflection of our experiences, we fall back on their cultural double: magic. This leads to fantasies of bodily coherence and potential intended to lessen worry, but instead propagates anxiety. Perhaps the reason for the continued production of the “witch” in pop culture has little to do with morality tales or the gender politics of the term (we still flock to J.K. Rowling’s novels, after all), but the necessary re-centering of ourselves—just as we are—as powerful agents of change.

Does this mean that I’m forsaking Fringe, or am not going to tune in to SyFy’s Ascension? No. But it does challenge us to not take SyFy’s “Imagine Greater” slogan at face value in our rush to script the future. Greater is not always “better.” Greater is not always “good.”

Photo via Lene Dietrich/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)