The Public Library of Science, the academic publisher more commonly known as PLOS, doesn’t lack for media coverage.

Launched in the early 2000s, PLOS was one of the pioneers in what’s called open access scholarly publishing. For decades, the scholarly journal industry has been coalescing into a handful of behemoth corporate entities who have leveraged their clout to raise subscription fees and force university library budgets into the millions of dollars.

PLOS, through the launch of seven journals ranging from PLOS Biology to PLOS Genetics, operates under the overarching principle that access to its articles should be completely free, and its staff has made every effort to ease the mode of discovery for the science it publishes. And it’s been rewarded for those efforts. In a little over a decade, it has become one of the highest impact scholarly publishers, with many of its articles generating national headlines. A quick search on Google News reveals that, in just the last week, thousands of mainstream news articles have referenced its work.

But someone like Victoria Costello, who is the senior social media and community editor of all of PLOS, knows the company isn’t adhering to its open access ethos if it’s merely penetrating the traditional media. So she spends a fair amount of time thinking about how to leverage online communities to generate interest in PLOS articles, even if it means bringing the scientists who penned the articles directly to those communities.

And that’s how she found herself emailing one day with a moderator at Reddit, which through its r/Science subreddit hosts one of the largest science-focused forums on the Internet.

A quick search on Google News reveals that, in just the last week, thousands of mainstream news articles have referenced its work.

“I think that we have become increasingly aware of how many of our readers and authors are regular redditors and follow r/science in particular,” Costello told me in a phone interview. “We also noticed that whenever one of our articles or blog posts lands on that page and gets upvoted, we have enormous spikes in visits. On more than one occasion, it’s caused our entire site to crash.”

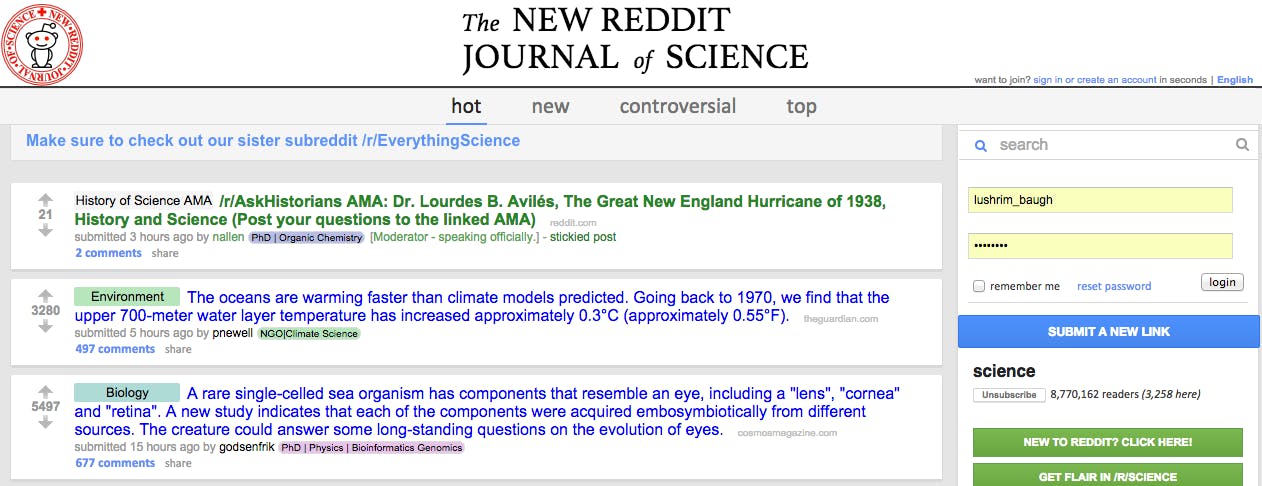

Last year, I profiled r/science’s launch of a regular Science AMA series. Short for “ask me anything,” AMAs have been a major bedrock of the Reddit community for years, allowing everyday users to interview A-list celebrities and even world leaders (Barack Obama’s 2012 AMA was so popular it temporarily broke the website).

Launched by Nathan Allen, a longtime moderator—or mod—for r/Science, the Science AMA series was geared toward inviting in some of the world’s most highly-regarded scientists to take questions from the Reddit masses. With its subscribership of over 8 million redditors, r/Science provided these scientists with a mode of one-to-one interaction they had never before experienced, thereby allowing them to further bridge the science communication divide.

These AMAs didn’t go unnoticed in the larger scientific community, least of all by Costello. She reached out to Allen earlier this year, and through their back-and-forth conversations, they decided to launch what would be called PLOS Science Wednesdays (a wink wink reference to public radio’s Science Friday), a weekly AMA that would feature a scientist who had recently been published in a PLOS journal. The first of these debuted a little over two months ago, and about a dozen total have been held since then.

“I think a lot of scientists certainly feel that they’re very concerned about the disconnect in science when it comes to the larger issues,” she said, citing widely-held misconceptions about GMOs and climate science. “We’ve sort of taken it on that we need to do a better of job of putting the science out there.”

It seems clear the r/Science community has been largely receptive to the series. Reading through the PLOS Science Wednesday discussions, I was struck by the range of expertise that could be found in a single question-and-answer thread.

In an AMA with Tom Baden and Andre Maia Chagas, two neuroscience researchers who developed laboratory equipment using 3D printers, one of the top-voted comments came from a grad student in neuroscience and chemical biology; he or she asked a question to such specificity and science-based expertise that a non-scientist would struggle to understand the question, much less know the answer. But then just a few comments down from that a user called glioblastomas asked a much broader question that wouldn’t require any specialized proficiency for those following along.

Andrew Farke, a paleontologist whose paper published in PLOS ONE last year documented the discovery of a new dinosaur, found that the questions asked to him in his AMA were easily palatable for a general audience.

Barack Obama’s 2012 AMA was so popular it temporarily broke the website.

“The sense I got from the questions was that most [of the participants] were fairly dinosaur interested but not necessarily experts,” he told me in a phone interview. “There were a few folks who I knew from their screen names were colleagues who decided to drop in and contribute, but for the most part it was people who were science savvy but not really scientists themselves.”

Though Reddit had been on Farke’s radar for quite some time, he didn’t really consider himself a redditor, nor did he have a user account prior to his AMA. But the r/Science mods and Costello had put together an easy-to-follow tutorial on how to use the site, and he found the process fairly easy to grasp. Within minutes, questions were flowing in, and his main challenge was choosing the order in which to tackle them.

“Questions that got lots of upvotes, those were the ones I would target first,” he said. “It was nice because there weren’t so many posts that I couldn’t answer most of them within the allotted time window. There was some triaging of questions, determining whether a question was actually answerable, or at least asked in good faith. Most of them were.”

I asked Farke to compare his experience with, say, getting his study covered in the New York Times. His response:

The thing that’s really nice about [the AMA] is it provides access to working scientists by people who don’t necessarily have that access. There’s a long tradition with museums and universities where you can go to a talk and you can ask some questions at the end of it, and that’s good if you live in a university town close to a museum, but there are a lot of people for whatever reason who don’t necessarily have that. … It’s not exactly the equivalent of having your research on the front page of the New York Times, that’s obviously different. But it does make [the research] more visible, and gives a chance for people who really want to engage with science to engage with it in a way that’s a little more personal than what’s offered by a newspaper article or a blog post.

Getting coverage in the mainstream press and on forums like Reddit has a much broader utility than simply informing the public. “If a study is written about in the Huffington Post, other scientists who happen to be reading the [news article] are going to find out about it,” said Costello. “And given the number of new papers, two million a year, this is really helping people find each other who want to collaborate and catch up on new science.”

According to numbers supplied to Costello by Reddit mods, the first PLOS Science Wednesday generated 172,000 views within the Reddit thread, and the two subsequent AMAs amassed around 72,000 (the initial spike was likely due to the novelty of the series). She’s also noticed downstream effects; one of the scientists who participated saw a spike of between 1,000 and 2,000 new visitors to his blog.

“Of course a smaller number go back to the article,” she said. “But it’s a significant number of readers, and it’s also a quantity, not quality, thing when it comes to actually bringing other scientists here to read papers. There’s nothing more important than having a scientist’s peers read his paper.”

Of course, it’s difficult to put such large numbers in perspective. In a world where social networks are collecting hundreds of millions of users, one can be forgiven if you become desensitized and lose sight of what it all means. Costello told me that she only really processed the impact when one of the scientists who partook in an AMA sent her this photo of a sports stadium:

“For comparison, this stadium, when full, has fewer people,” wrote the scientist. “Normally when I give a talk it is to 20-80 people…at a conference perhaps a few hundred. The Internet certainly changes the scale of things!”

Simon Owens is a technology and media journalist living in Washington, D.C. This article was originally published on his website. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook, or Google+. Email him at simonowens@gmail.com.

Illustration via Max Fleishman