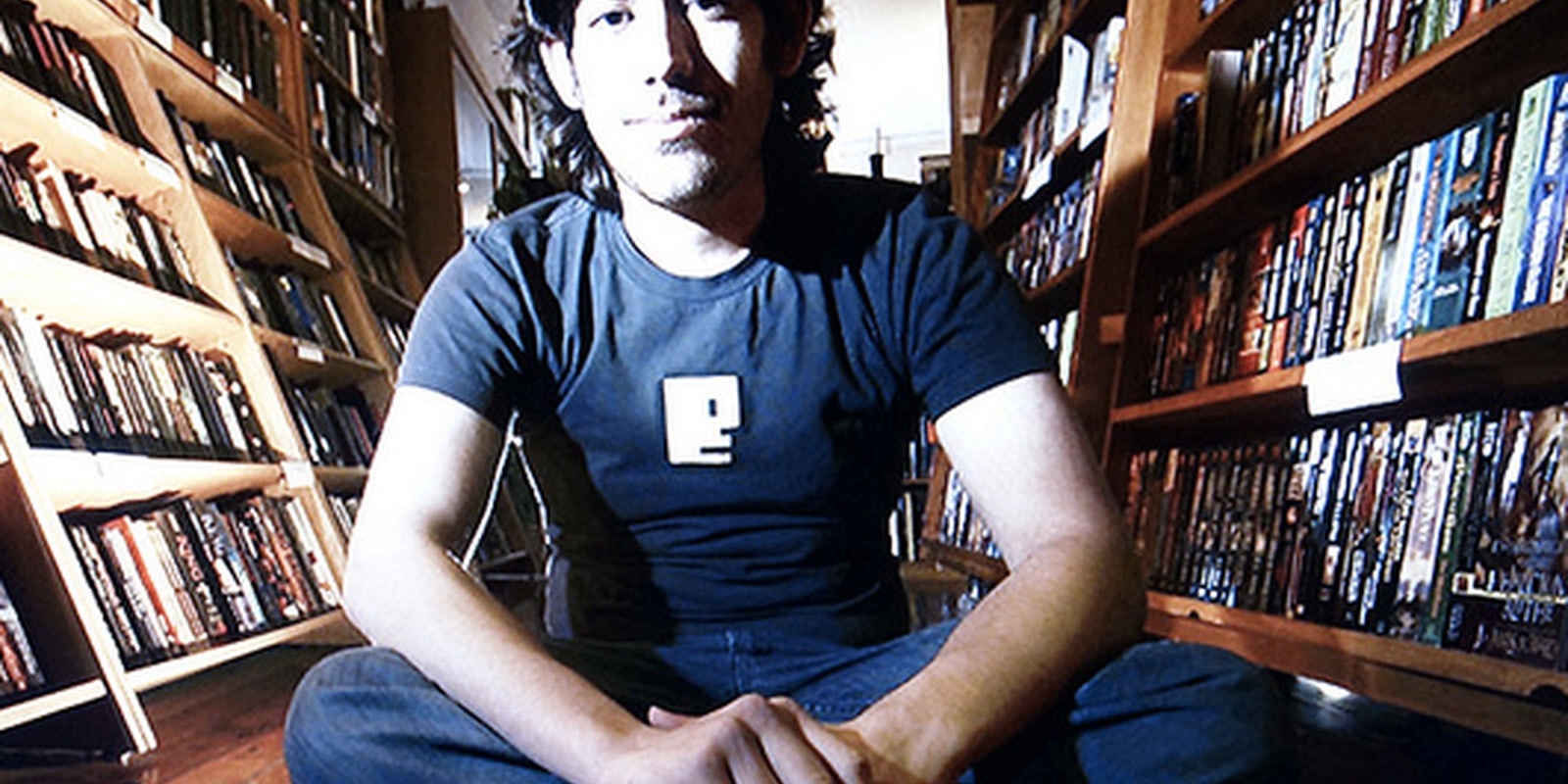

Prominent Internet activist Aaron Swartz took his own life in January, facing down a possible 35 year prison sentence for violating what many consider a technicality in an unjust law.

But Swartz was far from the only person charged dubiously under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), the so-called “worst law in technology.”

The law, passed way back in 1986—before the advent of the Internet as we know it—makes it illegal to gain “unauthorized access” to a computer system. But the definition of “unauthorized access” has been interpreted by prosecutors and judges to mean anything from malicious hacking to simply breaching a website’s terms of service.

Swartz allegedly violated the CFAA when he used MIT’s campus network to download a large number of documents from academic journal provider JSTOR, which was against the terms of that company’s user agreement. His death launched a widespread public debate about whether running afoul of a contract with a private company rises to the level of criminal hacking,

Swartz’s case has done more than any other to make the CFAA infamous, but he’s hardly the only person to be charged under the law for a seemingly trivial action.

Here are some of the most absurd real and potential cases arising under this controversial law.

1) Figuring out that AT&T is sharing its customers’ email addresses / Andrew “Weev” Auernheimer

“Hackers” are usually people who, you know, actually hack into networks. Not Weev. In 2010, the well-known Internet troll figured out a script that sent random customer codes to AT&T, causing the company to automatically send him the corresponding email addresses, which belonged to Pad users. Weev quickly gathered 114,000 of them—including some from NASA, DARPA, and the U.S. Military.

Far from hacking, Weev had essentially just guessed a web address—even an unsophisticated user could have visited that URL and come away with customers’ email addresses. Weev told AT&T of this serious security flaw, but also gave the addresses to Gawker.

Some praised him for figuring out a security issue: TechCrunch awarded him a “Crunchie,” saying “We don’t see much hacking here, and we don’t see anything really malicious. AT&T was effectively publishing the information on the open Internet.”

The Department of Justice wasn’t quite as enamored, and pressed charges. On March 18, 2013, Weev was sentenced him to 41 months in prison for violating the CFAA.

George Washington University law professor and outspoken CFAA critic Orin Kerr has agreed to represent Weev pro bono on appeal, publishing an extensive essay on what the case means for civil liberties online.

2) Telling Anonymous your former employer’s password / Matthew Keys

Reuters social media editor Matthew Keys didn’t do any hacking himself. But he did remember the login credentials for his old job at an affiliate at the Chicago Tribune, and in December 2010, he allegedly passed them on to a couple members of hacktivist collectiive Anonymous. Thus, Keys is allegedly responsible for hackers using that login info to deface a Los Angeles Times feature article. He currently faces charges of 25 years in prison and $750,000 in fines.

(Note to employers: You’re supposed to change your passwords when an employee who knows them leaves.)

3) Hacking into your school website and using pictures of your fellow students / Mark Zuckerberg

Zuckerberg is unique on this list for not having been arrested for computer fraud. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t violate the letter of the CFAA.

As noted by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, if the Department of Justice went after CFAA violators evenly, we probably wouldn’t have Facebook today. That’s because in 2003, founder Mark Zuckerberg created a site called Facemash, which let users compare two Harvard students’ pictures side by side and rate their relative attractiveness. This precursor to Facebook made Zuckerberg famous on campus, and the incident was later dramatized in The Social Network.

Harvard did accuse Zuckerberg of breaking security after other students complained about Zuckerberg using their school photos on Facemash, but the Facebook founder never faced criminal charges and wasn’t forced to leave the school.

4) Intending to share a manual that normally costs $13 / Robert Riggs and Craig Neidorf

In 1998, Riggs engaged in true espionage: He found a file on telephone carrier Bell South’s webpage (how, exactly, is unclear, but Bell wasn’t happy about it) that laid out the details of the company’s enhanced 911 program. Riggs shared the file with Neidorf, who intended to publish the file in his online hacker magazine Phrack.

Charges against both defendants were dropped when, under cross-examination, a Bell South employee revealed to the court that the file was available to the public for $13.

5) Creating a fake MySpace page to bully a minor / Lori Drew

In 2006, Drew, in response to her teenage daughter’s feud with classmate Megan Meier, allegedly created a MySpace page for a fictional boy to flirt with Meier. That “boy” began telling Meier the world would be better off without her, and the girl hanged herself in her bedroom closet.

Drew was initially found guilty under the CFAA for allegedly violating MySpace’s terms of service, which prohibited “harass[ing] or advocat[ing] harassment of another person.” She was later acquitted.

The CFAA was written before “cyberbullying” ever entered the lexicon and courts ultimately refused to extend it to cases like Drew’s. However, the incident sparked a nationwide discussion about passing laws specifically targeted at punishing Internet trolls.

Drew was also represented by Weev’s new attorney, Orin Kerr, who called her case “an extremely important test case for the scope of the computer crime statutes, with tremendously high stakes for the civil liberties of every Internet user.”

6) Texting / Neil Scott Kramer

In 2008, a 15 year old girl accidentally sent a text to Neil Kramer, an adult. The wayward message was the beginning of a serious texting and phone relationship. After seven months, Kramer met with her in real life. For the next four days, he proceeded to give her drugs, and the two had a sexual relationship until she called the police from a bar restroom.

Kramer was found guilty of “knowingly transporting a minor in interstate commerce with the intent to engage in prohibited sexual conduct,” but that wasn’t all.

A Court of Appeals found that Kramer’s phone—a Motorola Motorazr V3, which is not a smartphone—technically counted as a computer under the CFAA. Despite admitting that definition was “exceedingly broad,” the court “imposed an enhanced prison sentence” on Kramer for violating the CFAA.

Since Aaron Swartz’s suicide, activists (including the Electronic Frontier Foundation) and members of the technology community have rallied around CFAA reform. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) has also proposed a CFAA revision known as “Aaron’s Law,” under which terms of service violations would no longer necessarily violate the CFAA.

CFAA reformers may have a long road ahead of them, though. In a House Judiciary Committee hearing on March 13, lawmakers “expressed little enthusiasm” for updating the nearly 20-year-old act.

Photo of Swartz via Steve Rhodes/Fiickr