This March, some jerk reported me for name crimes.

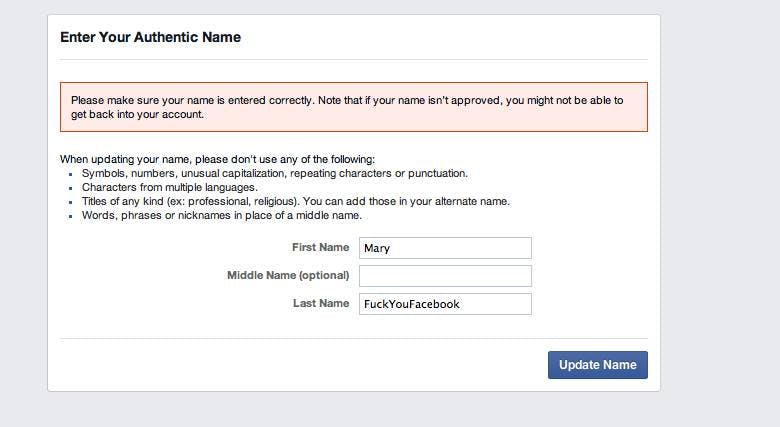

I logged into Facebook and was met with a pop-up that said my account had been flagged and I wouldn’t be able to get back in until I entered my “Authentic Name.”

I’d been using Facebook for years under a pen name. While it’s not on my driver’s license, “Mary Christmas” was a fairly well established persona. I edited a magazine ($pread, an award-winning sex industry rag) for two years using that name, wrote essays for numerous books as Mary Christmas, and even used the name on my bylines for the first several years that I worked as a reporter for Portland’s Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper Willamette Week. I traveled the world doing weirdo performance art with the Radical Cheerleaders under the name Mary Christmas. I published Xeroxed zines using the moniker in the days before the Internet (yes, there were days before the Internet). It’s not my real name, but I responded to it for a good 15 years.

But apparently a decade-plus paper trail still isn’t enough verification for Facebook. I was annoyed at being locked out of my account, and tried to change my name to Mary FuckYouFacebook. When several similar tries didn’t work, I finally settled on a name that the social network found acceptable—even though it is most definitely not my legal name either. That’s how I became Mary Zuckerberg on Facebook.

That’s why I found it kind of hilarious when Mark Zuckerberg told Buzzfeed yesterday that you can totally use any nickname you want on Facebook now. Zuck was hosting an AMA moment on his own profile on Tuesday, and a Buzzfeed reporter asked whether it might be a tad hypocritical of the social network to allow everyone in the universe to change their profile picture to a gay rainbow while simultaneously forcing trans (and other) people to use the names on their birth certificates. To that, Zuck claimed that we’re all just confused.

“There is some confusion about what our policy actually is,” Zuckerberg said in response to a question from BuzzFeed News. “Real name does not mean your legal name. Your real name is whatever you go by and what your friends call you.”

“If your friends all call you by a nickname and you want to use that name on Facebook, you should be able to do that,” he wrote on FB in response to Buzzfeed’s Alex Kantrowitz. Zuckerberg said Facebook “should be able to support everyone using their own real names, including everyone in the transgender community.”

Zuckerberg used the word “should” emphatically, if such a thing is possible. Because the truth is—and Zuck must know this better than anyone else—no one gets away with using a nickname on Facebook for very long. And some people don’t even get away with using the legal names they were given at birth, either.

Shane Creepingbear, who is Native American and a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, told the Daily Dot that he’s been locked out of his Facebook account three times for supposedly not having a “real” name. The first time was years ago, he said, and didn’t seem like a big deal. The second time, about two years back, Creepingbear had to send a copy of his ID to get back into Facebook. By the third round, he was getting understandably pissed.

“The last time occurred on Columbus day of 2014 and I was pretty fed up. I was frustrated and started clicking the links to settle things up and the language that it used was super marginalizing and offended me,” said Creepingbear. “Something to the effect of, ‘Your name does not meet our name standards.’ So I started documenting things and went on Twitter and had a mini hashtag tirade. It got the attention of the right people I guess and they reinstated my account the next day.”

Try again @Creepingbear apparently my family name does not meet @facebook standards. Way to go #ColumbusDay #facebook pic.twitter.com/HYiu55DYgh

— Shane Creepingbear (@Creepingbear) October 14, 2014

Creepingbear said that friends of his had experienced account disabling and name verification as recently as June. His partner Jacqui also was forced to prove the legitimacy of her name, and he pointed me towards a disturbing trend of racist white supremacists purposefully reporting Native American and indigenous people’s names in order to get them kicked off Facebook, which Colorlines reported on this March.

The Facebook harassment of indigenous folks prompted an April protest in which Native Americans and allies changed their names to Zuckerberg for a day and used the hashtag #IndigenizeZuckerberg.

But Native Americans aren’t the only people who have been forced to change and/or prove their names in recent months. The strict, legal-names-only policy has locked out transgender people, sex workers, survivors of abuse, and even at least one Facebook employee.

On June 27, a trans woman who used to work at Facebook wrote a damning essay for Medium titled “My name is only real enough to work at Facebook, not to use on the site.”

I always knew this day would come. The day that Facebook decided my name was not real enough and summarily cut me off from my friends, family and peers and left me with the stark choice between using my legal name or using a name people would know me by. With spectacular timing, it happened while I was at trans pride and on the day the Supreme Court made same sex marriage legal in the US.

This is a story that’s been told many times before. It is a story I’ve seen repeated time and time again as my friends have disappeared off the site, often never to return. This time there’s a twist: I used to work there. In fact, I’m the trans woman who initiated the custom gender feature. And the name I go by on Facebook? That’s the name that was on my work badge.

Zip’s being booted off the social network run by the company she worked for on a day saturated with LGBT rights and celebration is the definition of irony. Especially since Zip was the very person who brought us Facebook’s custom gender feature. The social network allows trans and gender non-conforming users to define their gender identity, then, but not their own names.

The reasons for using a non-legal Facebook name are myriad. For a trans person, it may be that they haven’t finished the sometimes lengthy and arduous process of legal name change. For those working in–or even just associated with–the adult industry, names can be a complex gray area that overlaps with safety and privacy.

Portland burlesque dancer Nowal didn’t want to use her legal name on a Facebook profile that was linked to the online scheduling of the strip clubs she used to dance at. So she used the name “ZeeGee” on her profile instead. Facebook recently locked her out of her account.

“It’s scary enough sometimes just working in the clubs. People pawing at you, like you’re an object and not a person,” said Nowal (who preferred not to use her last name) in an interview today. “I’ve heard too many stories of girls getting followed home from work. But to take away that persona and identity that can be used as a kind of shield or barrier from the creeps? Fuck you, Facebook.”

I connected with Nowal after posting a call for interviews in a private Facebook discussion group about the sex industry. She wasn’t the only person to respond. Within two hours, four exotic dancers commented—all had either recently been forced to change their profile names, or had friends who were currently locked out of their accounts, meaning it had happened within the past week. One, writing from her personal profile, said Facebook had just deleted her dancer profile, and another said that she’d had to send in her ID twice to prove that her unusual last name was legit.

“There are reasons for using a stage name as your Facebook identity,” Nowal said. “For me? It was a way to weed out family members that I don’t want to know about my life and a way to network and promote myself.”

In Portland, which has the most strip clubs per capita in the U.S., competition between clubs and dancers is fierce. A lot of dancers use Facebook to promote themselves and safely message with customers. Some also use a local social network created just for the Oregon strip club industry, XoticSpot. But while Xoticspot is convenient for many, it isn’t always free, and it can alienate those who prefer not to sign up for a standalone adult industry network.

Sometimes people associated with the adult industry are assumed to be using fake name when they actually aren’t. That may have been the problem for photographer London Lunoux, who shoots pin-up portraits and for years was one of the primary photographers for Suicide Girls.

A few months ago, Lunoux said she was locked out of her Facebook account and told she would have to wait 60 days to get back in. She sent a copy of her ID to the company to prove that London was indeed her legal name. Her middle name, Anastasia, somehow flagged the system as well.

“I’m not sure why anyone would think it was fake,” Lunoux told me. “I simply removed my middle name and then was given my account back. That’s just nonsense. Then to be able to add my middle name back, I had to send in my ID.”

Given the anecdotes I encountered while writing this story today, it seems pretty clear that there’s a disconnect between what Mark Zuckerberg thinks is happening at Facebook and what the company’s employees or internal flagging systems are actually doing. For some, what is most enraging about the authentic name policy is the fact that Facebook seems disproportionately strict about names while it appears downright lazy about things that actually harm people, like harassment.

Nowal recounted a recent problem in the Portland stripping community. She said a Facebook revenge porn page called Stranger Vixons was stalking local dancers and models and reposting their pictures to its page with captions like “Dirty whore” and “Slut.”

“Whenever a woman would comment on the misuse and harassment, the admins of the page would delete the comment, share a bunch of photos of the gal who spoke against the pages photos, call her names and then block them,” said Nowal of Stranger Vixons. “They even went so far as to share a photo of one woman breastfeeding her child on their page. Despite reporting it numerous times myself, in addition to at least 15 other ladies reporting it, the page ‘didn’t violate the terms of use.’”

The Stranger Vixons troll page has since been removed, though I did see it when it was still up. But similar slut-shaming efforts pop up all the time. According to an October 2014 Pew Research study, 37 percent of U.S. women have experienced online harassment. Younger women experienced unusually high levels, with almost half reporting that they’d been called offensive names, 15 percent reporting being stalked online, and 14 percent reporting sexual harassment.

“How harassing women, taking their pictures off of their profiles and slut shaming them is ok, but using a stage name on our accounts isn’t, I’ll never know,” said Nowal. “I mean, really. Using a stage name hurts no one. Taking that option away could seriously hurt so many.”

Photo via Charles Chen/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman