Siri, Google Now, and Cortana may be your personal assistants, but they aren’t your only confidants.

Last week, a Redditor going by the username FallenMyst posted about working for a company that reviews audio recordings from popular voice-powered services including Siri, Cortana, and Google Now. “I get to listen to sound bites [sic] and rate how the text matches up with what is said in an audio clip and give feedback on what should be improved,” her post reads.

Reactions ranged from “duh” to outrage. Regardless of where you fell on this spectrum, there was a follow-up question most readers wanted answered: Who is listening to these conversations, and how?

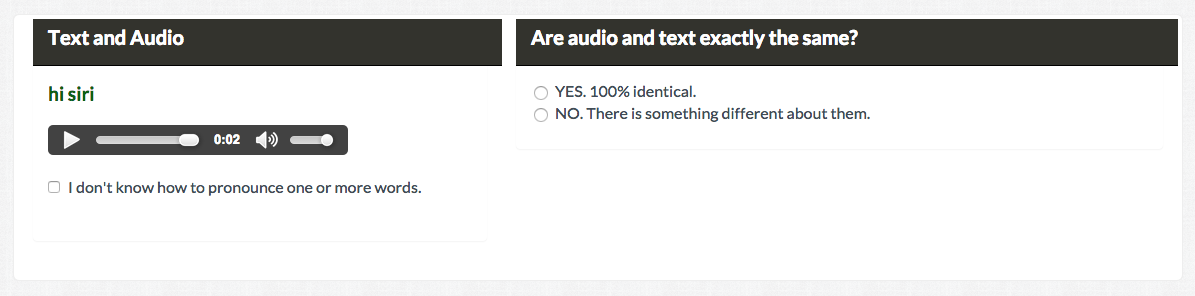

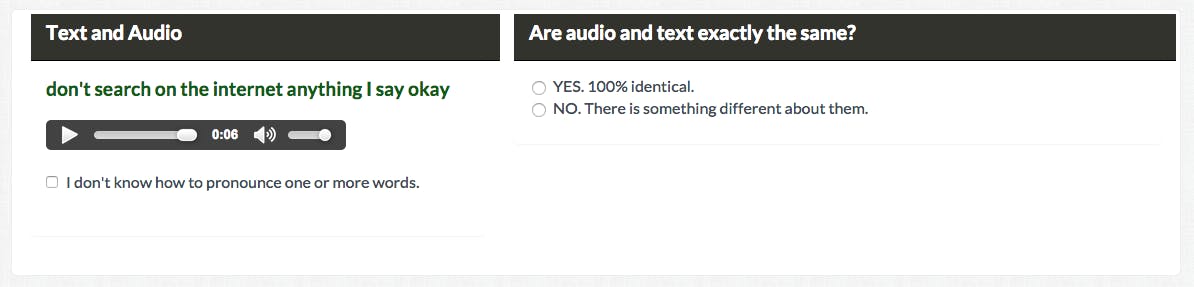

The job asked me to review audio recordings to ensure the text translation matched the spoken words.

One thing we know for sure is that your voice is being recorded when you use these services. In Apple’s Privacy Policy for Siri, it tells users, “When you use Siri and Dictation the things you say and dictate will be recorded and sent to Apple to process your requests. Your device will also send Apple other information, such as your name and nickname; the names, nicknames, and relationship with you (e.g., ‘my dad’) of your address book contacts, song names in your collection, and HomeKit-enabled devices in your home.” Similarly worded statements appear in Google’s support page for Voice and Audio Activity and Microsoft’s Windows Phone Privacy Statement.

This isn’t the surprising part, or at least it shouldn’t be. What is surprising is that if you choose to use these apps, you surrender control over your voice, information you’ve shared, and who gets to hear it once its spoken to these A.I. assistants.

Apple, Google, and Microsoft collect these recordings, but it isn’t necessarily people who work there that end up hearing them.

I decided to try and become one of these people. Just like the original Reddit poster, I took a job from CrowdFlower, where users can participate in banal tasks that require little skill and reward little pay. The job I signed up for asked me to review audio recordings to ensure the text translation matched the spoken words.

Sure enough, after listening to some of the recordings, it was fairly clear that they had been gathered from virtual assistants. Mentions of specific apps like Facebook, WhatsApp, or the Google Play Store made it clear that the recordings were taken from smartphones, while names like “Siri” and “Samsung” were spoken in others.

A spokesperson for Microsoft confirmed that this is standard procedure. “Microsoft shares sample voice recordings with partners under NDA [non-disclosure agreement] in order to improve the product.” A representative at Google noted that companies often outsource certain tasks, though would not provide confirmation that reviewing voice recordings was such a case.

The audio review process is an important part of improving the voice-recognition algorithms used by these assistant apps. A Google representative explained that the company has lowered its error rate with Google Now to around eight percent from 25 percent a couple of years ago, and that improvement is in large part thanks to analyzing voice recordings.

“The only way to improve these voice-recognition algorithms (many of which are based on machine learning) is to get better data about how the raw audio correlates with what people are actually saying,” Electronic Frontier Foundation Staff Technologist Jeremy Gillula, Ph.D. explained to the Daily Dot. “This sort of data labeling is a tedious, low-level job.”

Payment from the job on CrowdFlower was one cent per every 10 reviews completed, with a five cent bonus for completing 100 reviews with 90 percent accuracy. “To be honest I hadn’t heard about it being outsourced to people who are effectively volunteers, who aren’t even employees of a company, but it doesn’t surprise me,” Gillula said.

All of the companies behind these services insist that the recordings they collect are anonymized—there is no way to link a person to an account based on any gathered information; the recordings are voices without identities. “The samples are not associated with a consumer’s Microsoft account, and Microsoft has strict policies about how the data is used and retained. Partners do not have the ability to tie the voice samples back to specific people,” Microsoft’s spokesperson explained. Google and Apple offered similar statements.

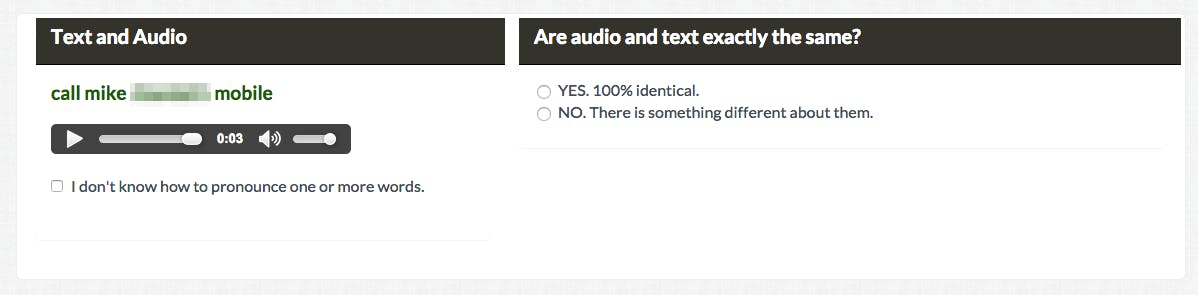

But within the recordings themselves, users willingly surrender personal information—information that is especially valuable in these review processes because they are so specific. Uncommon names, difficult-to-pronounce cities and towns, hyperlocal oddities that would be missed by broader strokes can be refined this way.

It’s also potentially identifiable information. “With devices like Amazon Echo, or Siri, or Google Now, even if the audio it records isn’t directly linked to your account, it could still contain sensitive info like your name, address, or other data depending on how you use the service,” warns Gillula.

“I certainly wouldn’t trust speaking to a virtual assistant about anything sensitive, that’s for sure.”

He’s right: While listening to recordings during my stint on CrowdFlower, I heard people share their full names to initiate a call or offer up location-sensitive information while scheduling a doctor’s appointment.

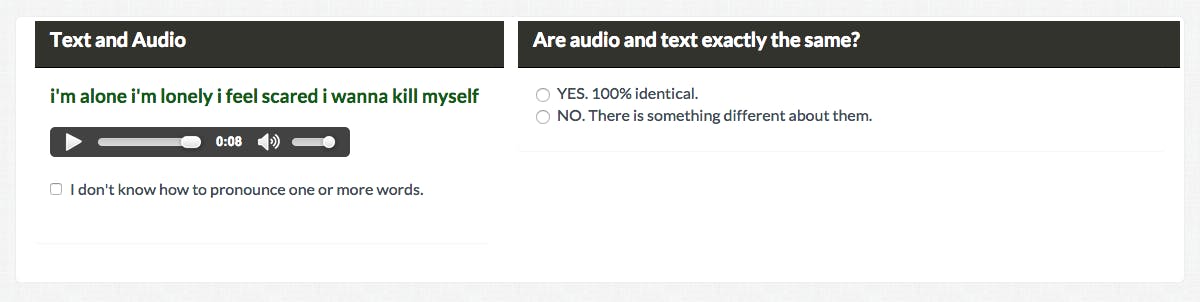

Even if it’s not data that is given up, recordings capture people saying things they’d never want heard, regardless of anonymity. There were tons of ridiculous sexual recordings of people prompting their assistant for lewd favors. There was also a recording of a user asking for help because they intended to commit suicide. Whether these comments were jokes or not, those are arguably vulnerable moments—and anyone who’s willing to make a few bucks gets to listen.

There isn’t much to keep people who are listening to these recordings from sharing them. The job security surely isn’t it (it pays less than $1 an hour). There could very well be a Tumblr or a Twitter handle out there dedicated to spewing out some of the snippets.

The companies that are providing these jobs remain shrouded in mystery. The company listed on the CrowdFlower page doesn’t even exist under the name given, “Walk N’Talk Technologies.” A CrowdFlower representative told the Daily Dot that to sign a contract with the service, “companies are required to provide correct information about their companies,” however they may remain anonymous when running jobs, leaving the person completing the work in the dark about who they work for. CrowdFlower would not provide further information about the client using the name Walk N’Talk Technologies, stating, “We take customer privacy very seriously and are unable to provide customer information that is not already publicly available.”

While there may be non-disclosure agreements between the major tech companies and the companies they outsource work to, there is no privacy agreement for users completing these menial tasks.

“Anything you say to one of these devices could end up all over the Internet. I certainly wouldn’t trust speaking to a virtual assistant about anything sensitive, that’s for sure,” said Gillula.

However, a representative at Google presented the voice recognition feature in Google Now as a security tool. Because Google Now has a recording of a user’s voice, it can prevent others from trying to access Google Now features. Which raises a question: If a voice is unique enough to act as an authentication method, is it not unique enough to be an identifying feature of a person? And if it is, shouldn’t it be better protected? Shouldn’t we, the users, get to opt-out of have our voice recordings listened to and analyzed? It’s the age of opt-out, why shouldn’t that apply to our voices?

There are little steps users can take to curb some of these concerns. Google Now and Siri—which both can be activated by voice prompt, meaning your mic is always listening for the prompt but not recording until activated—can be disabled on certain screens and data can be cleared from their respective settings. Microsoft likewise allows recordings to be removed from Cortana. There’s no indication if those recordings are also pulled from the databases that store them or if they can still be used for review purposes.

But if you don’t want your voice recorded by these services and farmed out to workers making enough for a cup of coffee from a day’s worth of work, then you only have one real option: Don’t use them.

“There really isn’t very much short of not using these virtual assistants,” Gillula explained. “You could try to self-censor yourself, but at that point deciding what is and isn’t safe to say would probably become more of a hassle than just typing your request into a search engine. Unfortunately, users’ options here are pretty limited.”

A spokesperson at Microsoft all but confirmed this as well, stating, ”You can turn Cortana off, putting you in control.”

Illustration by Max Fleishman