I got up at 4am Tuesday morning. It was still dark. I had only slept four hours, five tops. I ate a banana, nothing else. I then walked about two or three miles in the dry Vegas sun. I was sluggish, tired, and I had that gnawing feeling in the back of your throat when you’re getting sick.

And then, I let Thync zap my brain.

Wearable technology, though more prevalent than ever, has plenty of critics. A lot of people hate the name, and even more despise the purpose: tracking everything about yourself, obsessing over your personal data like a narcissist.

Of course, most wearable technology and personal data-tracking has a purpose. It’s supposed to help us make more informed decisions about our minds and bodies based on what it delivers. We can change or modify our habits if we get too much or too little sun, food, exercise, sleep, etc.

But what about wearables that don’t ask you to change anything? What about wearables that just… change you? Well, they’re coming. Or rather, it’s coming.

Thync has been quietly gaining attention for a couple of years now, popping up here and there when we talk about next-generation wearables. The team is at CES this year, giving private demonstrations, and I was able to go hands-on—or rather, heads-on (sorry)—with the upcoming product.

I met Thync Executive Director Sumon Pal, a former Harvard neuroscientist, so I could get some time with Thync. Pal tells me that he and the Chief Scientific Officer at Thync, Jamie Tyler were both working on their doctorates at Harvard when they teamed up with CEO Isy Goldwasser. “This company was formed on this idea that we could merge biology and technology so you could tap into your own brain and dial up your best self or different mental states on demand,” he tells me.

“Most of what you see in wearables today is based on sensors and those devices give you feedback and ask you to change yourself or change your behavior in some way to get to a desired place,” he continues. “Our device just does it. We’re not sensing anything, we’re activating the right parts of your nervous system with very small amounts of electrical energy to activate nerves that are going into the brain and the brain itself so we can actually change your mental state.”

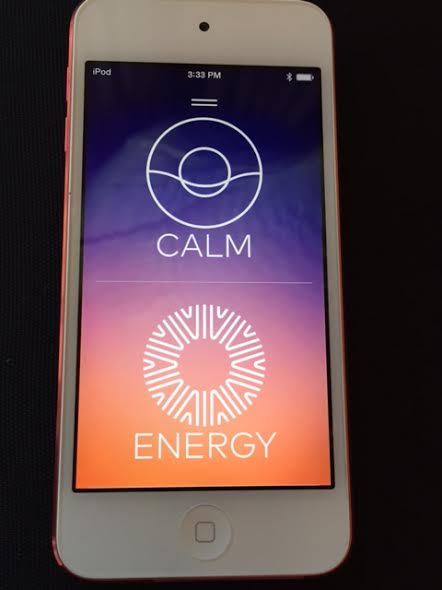

Right now, there are two mental states you can use Thync to achieve: calm and energetic. In the future, the device will help you get more specific, for instance it could help you with creativity, focus, willpower.

Pal likens what Thync does to alcohol or caffeine: Both chemically alter your brain. He says that Thync doesn’t want to replace these markets, rather that it sees them and realizes that brain alteration is something we want.

While the unit I used isn’t the finalized physical version, the best way to describe it is as a two-part device, one of which is fastened to the front of the right side of your temple, and one behind your right ear. It’s not a helmet, which is what I absolutely assumed it would be. It’s a relatively discreet, sort of dual patch system (but again, I was using a prototype unit; the finished product will be much sleeker).

After Thync is attached, you use the app to control it. The app prompts you to choose between what you want to feel, calm or energy. Seeing as I got up at 4am this morning and had hours of CES meetings left, I chose energy.

Shortly after, I felt the tingles start.

The patches—or “energy strips”—were sending small amounts of electric shocks to my brain. I started around 50 percent, quickly bumping things up to 72 percent (you control this via the app). A graph shows you when a big “tingle” (as I’m calling them) is about to hit, and sure enough, as I watched the pattern move, a big “tingle” hit.

Whoa.

It didn’t… hurt. Hurt isn’t the right way to describe it. It felt like a tightness; it felt like the patch was trying to crawl across my skin. But—if you can believe this—in a good way.

And while Thync was attached to the right side of my head, occasionally I felt “tingles” pulling and hitting my brain on the left side and in the middle.

I was feeling progressively awake and aware. Granted, I had patches stuck to my head sending gentle vibrations to my brain, so that might have been part of my sudden alertness. But still, after 20 minutes of Thync I just felt… better.

It’s hard for me to say if the placebo effect had any part here. I was told that Thync would make me feel more energetic, and I felt something and did something that enabled the device, and so I suppose it’s possible I convinced myself of something. Still, I really believe that the tingles made me feel differently afterward, more alert and tuned-in.

I asked Pal if people have been critical of Thync at all. Certainly the phrases “electrical” and “mood altering” are enough to set consumers on edge. Not really, he says. And to be fair, the chemical alterations we put our bodies and blood through are so accepted it’s difficult to find fault. Still, the idea of changing your brain to make you feel something… I mean, that’s what my druggy friends did in college, right?

But the obvious difference is that Thync is cutting out such damaging drugs. Drugs that I would admittedly use for different reasons, especially at this show: I’m basically shooting coffee and Emergen-C, and I would not say no to a Xanax for my flight back. I would substitute these for Thync, hands down.

Thync will be released sometime this year, but a date hasn’t been set. “Still to be determined,” says Pal. “We are just working things out and don’t want to be one of those companies that unveils it and then there’s a huge lag.

“We’re doing a lot of testing now and finishing the technology.” Pal says that Thync has hugely changed since the team started, and that after more than 100 internal studies and mass research, the product is finally edging toward a launch. “We wanted the vast majority of people to wear this and have a meaningful experience from it.”

Photo via neil conway/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)