One of the things I truly enjoyed most in middle school was AOL Instant Messenger. I begged my father for weeks to let me get an account, and once it was mine, it was like an extension of myself. I loved the feeling of leaving the computer for hours on end to see how many pings my Away Message would have once I returned.

The rituals of AIM were so enjoyable for me because I was creating an identity for myself. Not one that was all that different from who I was in real life, but it was a new, smaller part I was able to add to the equation. I was becoming more available to my friends, and it came complete with fun emoticons and cute screennames.

The Internet wasn’t overwhelming to me then. I couldn’t wait to log on, to see what everyone was really up to. Somehow there was more honesty there then there was at school; AIM (and Myspace, and then eventually Facebook) was like the sleepover after the big birthday party. Only the real friends got to stay, and that was when the fun really started.

But as I’ve grown up, the tables have been turned: Social media is now the massive, noisey party beforehand—the one everyone gets to go to. And it’s not always a fun party anymore. It’s constantly pinging, notifying, blinking, buzzing, vibrating, and texting. It’s enough to make your head swim.

In the wake of the overwhelmed Internet have come a new class of apps—apps to keep us from connecting.

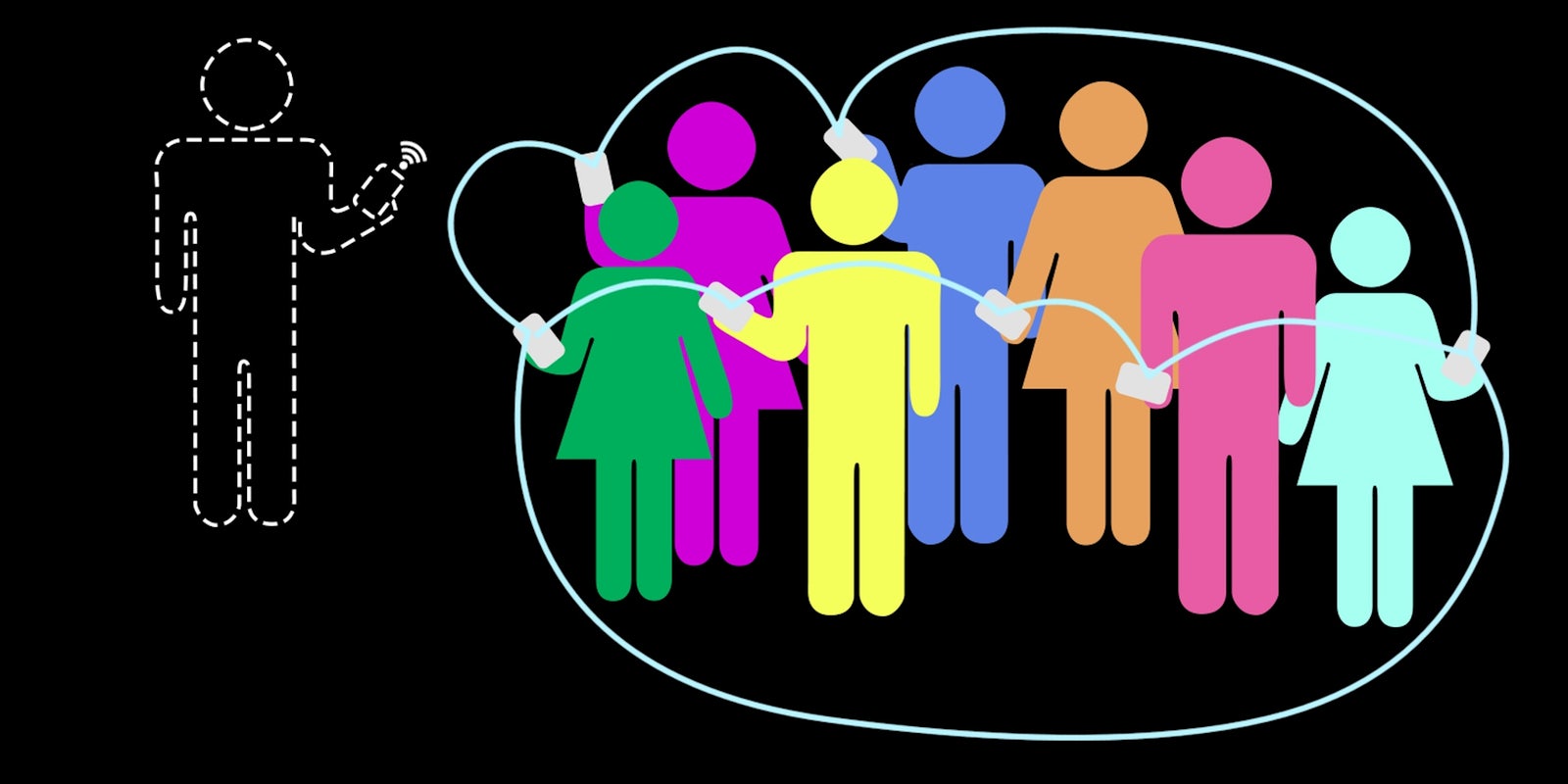

Split (which just launched last week), Cloak, Avoid Humans, and Hell Is Other People are anti-social social apps, as antithetical as that may sound. For the most part, these apps function by reading your location, leveraging your social networks and the location data posted there by your friends, and helping you… avoid them.

“I think we’ve all sacrificed a lot in terms of giving up our online privacy,” Cloak creator Chris Baker told me via email. “So now when people see things that use that sacrifice to create value like the offer of privacy in real life, that’s a good thing, and clearly worth talking about.”

Scott Garner, the creator of Hell Is Other People, had a slightly different perspective.

“I think there are two angles to the ‘anti-social media’ buzz that’s going on now—one is about using this kind of software to enable anti-social behavior, and the other is about making a statement about social media itself,” he said.

“Hell Is Other People was meant as an experimental artwork to explore these issues, but other recent projects seem to be trying to make something useful—which is ultimately ridiculous, of course, because you have to be ‘friends’ with people on these networks before you can properly avoid them.

“I’m reminded of Guy de Maupassant who hated the Eiffel Tower, but supposedly often ate lunch there because it was the only place in Paris he could avoid looking at it. I think the important thing here is that people are starting to question the role of social media in their lives—it’s very much something in the air right now and I expect to see more and more people exploring it.”

Plenty of studies are calculating the terrible things aggressive Internet use is doing to us. Younger users who are living their lives logged on are in danger of suffering from social anxiety; college kids who struggle with a number of mental illnesses are more likely to be addicted to the Internet.

Life is hard and overwhelming, and now that we’re living our lives out via apps and sites, collecting it and analyzing it over screens and text messages, the medium that’s delivering the things that give us anxiety—friends, family, work, conflicts, money—is naturally the thing we’re going to blame and try to fix.

The idea that we need apps to avoid the work of other apps is on one level lunacy, and on another, makes all too much sense. The Internet is no longer a thing we willingly log into momentarily and out of when we tire of it, returning to our IRL selves. It’s now a layer of our identities that follows us around everywhere, across platforms and into the actual world.

Perhaps the only way to fight it is with apps that force us away from it.

Illustration by Jason Reed