Professional dominatrixes, VIP escort services, and independent workers alike are speaking out against LinkedIn for perpetuating the stigma that their work is not legitimate.

The job-networking site changed the language on its user agreement last week to include specific language banning sex work. The way the update reads, one may not:

Upload, post, email, InMail, transmit or otherwise make available or initiate any content that: Even if it is legal where you are located, create profiles or provide content that promotes escort services or prostitution.

The reaction from sex workers and those in the prostitution industry, especially brothels and workers in places such as the counties in Nevada where sex work is legal, has been largely negative. Adding specific language to ban sex work from LinkedIn, they say, suggests that the site views sex workers as troubled or troublemakers.

Mistress Matisse, a professional dominatrix and writer in Seattle, posted a link to the story on her Twitter Wednesday, expressing displeasure with the new rules. Matisse told the Daily Dot she doesn’t use LinkedIn anyway but that her problem is more the principle of the matter.

“I think it’s ridiculous—and simply unjust—that consensual adult sex work is illegal in some places, and that it’s so stigmatized that people would be offended by even seeing the profile of a sex worker,” she said. “There are lots of professions that are regulated very differently from country to country, and I doubt that users expect Linkedin to ban ANY mention of ANY profession that MIGHT be illegal in ANY country. That’s the part of this that’s wrong.”

LinkedIn’s new rule—which extends not only to prostitution businesses but to freelance or self-employed sex workers the industry calls “independents”—is a part of a larger problem associated with sex work on social networks. In 2010, Craigslist caved into outside pressure and famously got rid of its adult-services section. A quick LinkedIn search as of yesterday revealed that the site still allows you to search for strippers and porn actresses under “Jobs.”

Yelp, a site where businesses might advertise their services, does not show any escort services or brothels in search results (even in legal Nevada counties), but it does allow discussions on where to find prostitutes in its “conversations” section. There are also separate sites like Yelp for prostitution and escort services that are currently up and running, including My Red Book and The Erotic Review.

“There really is no story here,” said Doug Madey, an associate at LinkedIn’s Corporate Communications. “Here’s the reality—we have always prohibited these kinds of profiles. The recent change in our UA just makes it more explicitly prohibited.”

In the old LinkedIn user agreement, he said, the company had covered the area of escort services and prostitution by saying that one could not use a profile to promote anything “unlawful.” However, in some countries, sex work actually is lawful, so the new language isn’t legal, just the company’s personal position.

“It was confusing, and a little too general and vague, for our members,” Madey said. “And the whole purpose of our rewrite of our user agreement was to make it clearer for our members. … But to be totally clear, our policy has not changed. We didn’t allow profiles to promote these kinds of activities before, and we still don’t.”

As LinkedIn becomes aware of profiles and other activity on the site that may be in violation of its policies, he said, the company will take “appropriate action.”

LinkedIn might be used by sex workers in conjunction with other social networks like Facebook and Twitter to create a personal brand for a prostitute’s persona, said Stacey Swimme, a sex worker for the past 15 years and an advocate for sex workers’ rights. She said LinkedIn’s ban is the result of the false idea that sex workers aren’t “normal” people.

And if a large social-networking site like LinkedIn is able to ban sex workers, what is stopping other large sites like Twitter, Facebook, and even Google?

“If he’s saying this is a non-story,” she said, responding to Madey’s comment, “that indicates to me that [LinkedIn’s] attitude is that the people that they are discriminating against aren’t actually people, and that these aren’t lives we’re affecting.”

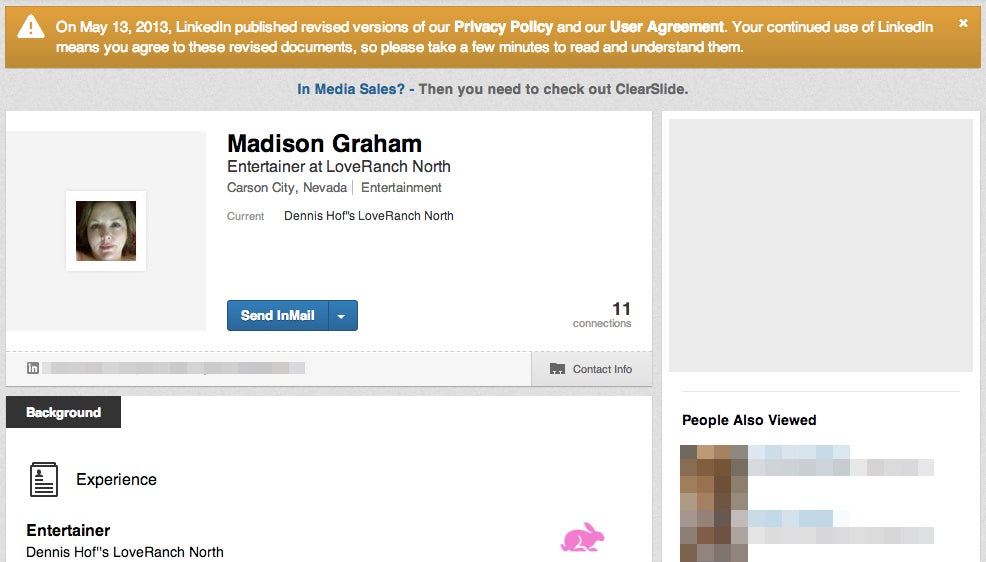

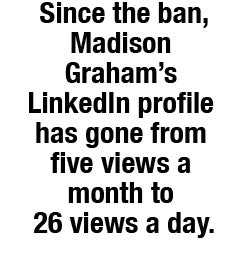

For the sex workers that actually use LinkedIn, the ban affects their ability to keep in touch with clients, who might be businessmen or CEOs. Madison Graham, a prostitute at Dennis Hof’s Love Ranch North in Carson City, Nev., currently has a LinkedIn profile that she’s worried every day will get taken down. She joined the site to procure regulars who wanted to message her for repeat connections. Before the controversy last week, her LinkedIn profile had about five views per month. Since the ban, her profile has received about 26 views a day,” Graham said—a significant increase due to upped Googling of “prostitution + LinkedIn.”

Her boss Hof’s profile has been removed, and he’s been vocal in the media recently protesting the ban. Graham told the Daily Dot that she understands if the company wants to take down illegal prostitutes who are using LinkedIn to break the law, but she stressed that her work is legal.

“I have a federal background check. I have medical tests every week. I have a license from the county I’m in,” she said. “I’m fully legal. I pay taxes on my money, so don’t question the morality of Nevada. They’re not the moral police. I’m a legal business, and I should be treated with the same respect as any other legal business.”

Sex worker and activist Siouxsie Q, like most employees, entered her profession by choice and wants to be taken seriously as an entrepreneur. Sex work is real work, she insisted, but those who choose it as a job are treated as second-class citizens.

“I’m just like any other American girl working hard to pursue her dreams,” said Siouxsie, who also created a podcast called The WhoreCast in the hopes of humanizing sex workers. “Under LinkedIn’s new policy, I would not be able to have a profile or make professional connections because my podcast certainly ‘promotes’ sex work.”

Some of the users listing “prostitution” in their profiles might actually work to help victims of human trafficking, so it will be interesting to see if the ban affects them as well. It will also affect those involved in prostitutes’ rights activism and services. Siouxsie worried that LinkedIn might hone in on places like Solace SF, a faith-based organization that provides compassionate care to sex workers, SWOP (The Sex Worker Outreach Project), and SWAFF (Sex Worker Allies Friends and Family), a resource group for families and allies of sex workers.

Some of the users listing “prostitution” in their profiles might actually work to help victims of human trafficking, so it will be interesting to see if the ban affects them as well. It will also affect those involved in prostitutes’ rights activism and services. Siouxsie worried that LinkedIn might hone in on places like Solace SF, a faith-based organization that provides compassionate care to sex workers, SWOP (The Sex Worker Outreach Project), and SWAFF (Sex Worker Allies Friends and Family), a resource group for families and allies of sex workers.

Kathy Harris, marketing director for SLIXA, a website where professional independent escorts, escort agencies, and erotic massage and BDSM practitioners advertise their legal services, said the company planned to join LinkedIn soon as a way to build SLIXA’s professional brand and to network like any other business.

“It’s a real dichotomy to image yourself as an online professional directory and then exclude legal professions and companies,” she said of LinkedIn. “Most professionals are so used to this age-old tactic that they probably won’t bat a pretty eyelash at LinkedIn’s BS.”

Australian escort Madison Missina said that in her country sex work has been largely decriminalized. LinkedIn exists as an international website, so it should be respectful of international laws.

“We abide by laws, run our businesses legitimately, and pay taxes. There is no difference between my business as a sex worker and my neighbor’s, who’s a beauty therapist,” Missina said. “It’s a shame that these so-called ‘pioneering’ Internet companies take such a backward step and prohibit people from being open about their legal occupations.”

Violet Rose, a sex worker in the U.K., agreed.

“It should not be up to businesses to take a moral stance on whether certain occupations should or should not be included,” Rose, who runs the site Stockings and Seams, said. “[I]t is totally unacceptable that profiles for our careers should be removed from such an important global networking tool as LinkedIn. That sex workers should be banned from connecting with peers and colleagues shows that LinkedIn doesn’t see the sex industry as capable of being a professionally networked one, let alone the idea that sex workers should be free to be added by clients, the same as a plumber or a graphic designer can be.”

Especially in places where prostitution is illegal, Siouxsie said, LinkedIn’s ban on sex work will make it harder for sex workers to connect with one another. Sex workers’ rights campaigns are built on sharing resources and fostering community, which the Internet in general has been integral in helping sex workers do.

“Now more than ever, we are online and able to connect with activists across the globe on the issues that we face as sex workers. LinkedIn’s new policy limits our access to the tools we need to build our movement and make change possible,” Siouxsie said. “If sex workers are banned from these online spaces, we are essentially banned from participating in the online community and the global economy.”

“That is our only safety mechanism,” said Swimme. “LinkedIn is saying they’re fine with sex workers not having a safety network … to protect each other from rape, assault, theft, extortion. So for me, social media and the sex industry is more about sex workers networking with each other than with finding clients.”

“That is our only safety mechanism,” said Swimme. “LinkedIn is saying they’re fine with sex workers not having a safety network … to protect each other from rape, assault, theft, extortion. So for me, social media and the sex industry is more about sex workers networking with each other than with finding clients.”

Plus, she said, LinkedIn isn’t even addressing the real issue; the ban is a bandaid on a geyser. The number of people turning to sex work increases every day, especially in a down economy and especially for disadvantaged groups like women and trans people. If LinkedIn actually cared about prostitution, Swimme said, they’d be about campaigning for fair wages for women, people of color, and trans folk, or an end to education discrimination and unequal pay. Banning sex work doesn’t solve anything, she noted, because sex workers will just move to another site.

“This ban,” she said, “is about scapegoating and finding a boogeyman instead of actually looking at the real issues.”

Illustration by Fernando Alfonso III