Most examinations of security and privacy online are written by geeks, and largely only readable by nerds. The problem with that approach, of course, is that most of us are neither. We do not have the obsessive interest in and depth of familiarity with the guts of our computers and the niceties of the roads they run on.

Well, lucky for you, some tech reporters are none too bright and enduringly lazy. Their computers are a mess of default settings and haphazard attempts at security. For such hen-wits, their online security regimes are the equivalent to a home security plan consisting solely of windows the previous tenant painted shut.

So, let’s take a look together and see what basic, simple measures we can take to maintain maximum security for minimum effort. After all, as we mentioned in a previous article, Microsoft Research’s Cormac Herley made an extremely important and underappreciated point:

Most security advice “offers to shield (users) from the direct costs of attacks, but burdens them with far greater indirect costs in the form of effort.”

We’ll try to keep those costs down.

Secure your junk, physically

Photo via David Woo/Flickr

As often as we hear about spy-vs-spy type cybersecurity campaigns, like the recently uncovered Red October spying program, a great deal of cybersecurity breaches are physical. From UPS losing Citibank user data somewhere in its transportation chain to the creators of Stuxnet relying on seeded thumb drives physically sprinkled about the place and physically stuck into a USB port, people in places doing things is one of the easiest, and most easily preventable, way to screw up someone’s online world.

- Don’t leave your laptop and mobile devices unsecured in public or in the workplace

- Do not use unvetted media, such as thumb drives and CDs, in your devices

- Do not leave your devices powered up while you are not there to watch over them, unless you …

Secure your junk, digitally

Every device to speak of offers you the option of securing it digitally. My laptop, for instance, requires a password. My phone offers the ability to lock when not being used, only unlockable using a shape-based password gesture.

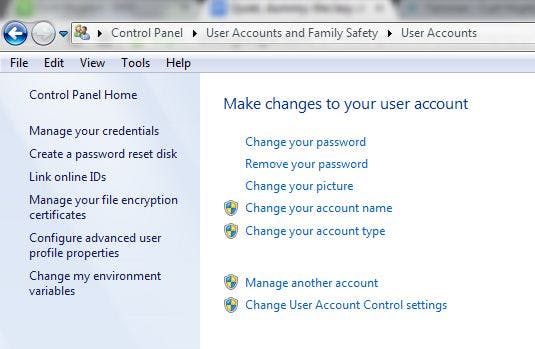

Most of these options are available under some variant of a “settings” field. For my laptop, for instance, it is available under the Control Panel, reachable by right-clicking on the Windows button in the lower right-hand corner of the screen (or the Apple menu in the top left, if that’s your thing) or via the Windows Explorer navigation frame.

On my mobile phone, an Android OS device, you can set the screen lock and password in much the same way, under the Location and Security settings.

If you set up your devices so that they default to password-protected when not being used, or can be locked when you step away from them, there is much less of a chance that someone will slip in and use your accounts to commit some perfidious act, or hit your device with a malware-infected medium of some sort.

Use built-in security tools

All devices come with security measures. They are not always the most effective ,but they have the benefit of actually being there. For instance, on my laptop, I can elect to encrypt the contents of my hard drive using BitLocker Drive Encryption. Anyone attempting to access the contents of my drive remotely should encounter an ass-ton of gibberish. They can hack it if they’re good enough, but it should at least prevent opportunistic smash-and-grab data theft.

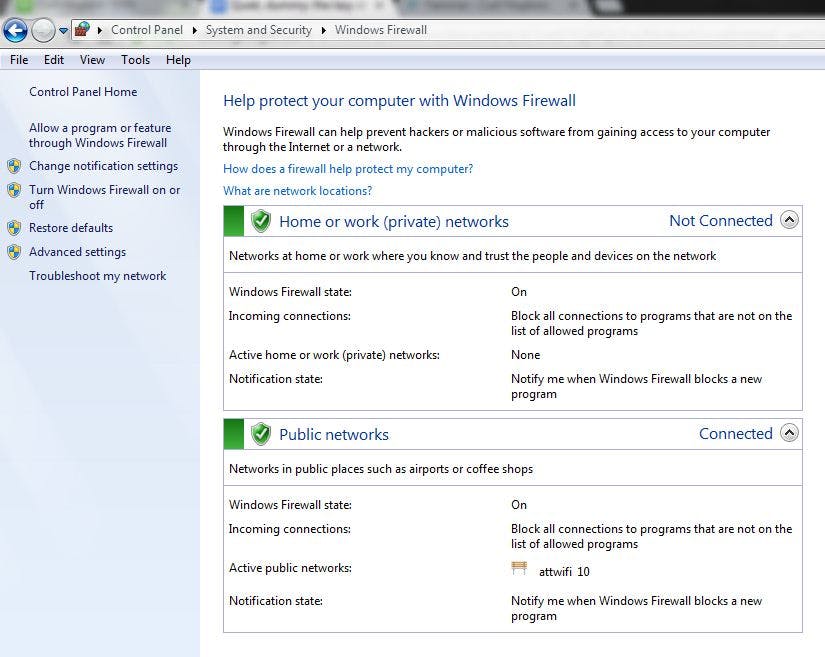

Built-in security firewalls and virus/malware detection programs are standard with most devices. Use them. They are far from perfect but they are, by and large, useful. After all, if your goal is to make your devices and accounts impregnable, you won’t. Your goal should be to make it more trouble than it’s worth, sending probing hands on to easier targets.

So to do that, make sure your firewall is turned on and adjusted to whatever height you are willing to put up with. Too high and it will ping you for permission to do practically anything; too low and it might as well be turned off.

Most devices come with a subscription to an antivirus/antimalware service, but that subscription usually runs out after a year or two. Either maintain the subscription, or download a free service. Regardless of what type of software and service you use, make sure you automatically update your virus definitions on a regular basis and that you schedule regular, frequent scans of your device.

Your email is evil

As we have explained at length elsewhere, any time you get online, whether to browse, to email or anything else, you are at the mercy of a third party.

Third party email providers—which is to say, all email providers—may well keep copies of your emails, even after you delete them from your account. Those companies, almost all of whom are large U.S.-based media companies, are obliged to turn over information on their users, including their emails, whenever asked to do so legally. One of the problems with this is that there are many more “legal” ways for a law enforcement or intelligence agent to ask for your information. In many instances, warrants are not even required.

This is all quite aside from the ability of hackers to capture information, singly or en masse, that will allow them to comb through your email for personal and economic information, like ecommerce passwords, which they can use for personal gain.

So there are three ways of eliminating or at least limiting, your exposure. You can stop using email. You can limit your use of email, for instance never communicating financial information or excising any mention of personal identifying details. Or you can encrypt.

Encrypting is no fun. You have to encrypt your connection, the messages themselves and your stored messages. The first is not too tough. Most email systems allow for secure socket layer/transport layer security. SSL/TLS can often be triggered by adding an S to the http in your address bar. If that does not automatically encrypt your connection, go to your settings for your email program and look for encryption, often under advanced settings.

To encrypt your email messages, you can use the encryption offered with the email service, if it is offered. When offered, as with Microsoft Outlook, it is usually secure/multipurpose Internet mail extensions (S/MIME) encryption. Otherwise, you’ll have to download a tool yourself, such as a pretty good privacy (PGP) program or add-on, like OpenPGP.

To exchange encrypted messages with a recipient, you will both have to install security certificates on your computers (available from companies like Comodo), generating “public keys,” or strings of characters like long passwords, which you will need to share with each other ahead of time.

One easy way to encrypt your stored email is by encrypting your hard drive. (See above.)

For more information on email encryption, PC World and Lifehacker both have good, detailed reference articles.

Browse securely

The easiest way to securely browse the Internet is to do so in a way that does not divulge to anyone what you are looking at, who you are, and where you are browsing from.

You can get around this sort of identification by using a proxy server. Proxies are Web browsing intermediaries. As a user, you go to the proxy site and the proxy site fetches Web sites for you, making it more difficult for anyone to pinpoint your actual location or identify you by your computer’s IP address.

There are many lists of proxies available with a quick search. The problem is that employees of blocking software and representatives of government agencies make sure they are up with the latest proxies as well. Peacefire’s Circumventor is a good source for a constantly updated list of usable URLs.

Another option is Tor. Tor is a “network of virtual tunnels” that make tracking the location and identity of an Internet user much more difficult. This frustrates what is called “traffic analysis,” that can infer from Internet traffic paths and use patterns where a user is and who they might be. It also circumvents content blocks while blinding hackers to destinations they might benefit from knowing, such as banking and ecommerce websites.

Tor requires a user to either download connection software or employ the “Tor browser bundle” run off a USB drive, if they wish to avoid downloading the software to their hard drive.

There are two issues to note with using Tor. First, it can slow down your browsing. Secondly, if you are trying to avoid being seen visiting certain sites, it will work, but in some contexts being seen to visit Tor itself will raise suspicions.

Facebook, Twitter and who knows what else

Sites like Facebook, Twitter and other social networks are to your digital edifice what dog doors are to your physical house: additional entry points for invaders and exit points for heat, kids and, of course pets. OK, the metaphor is not perfect.

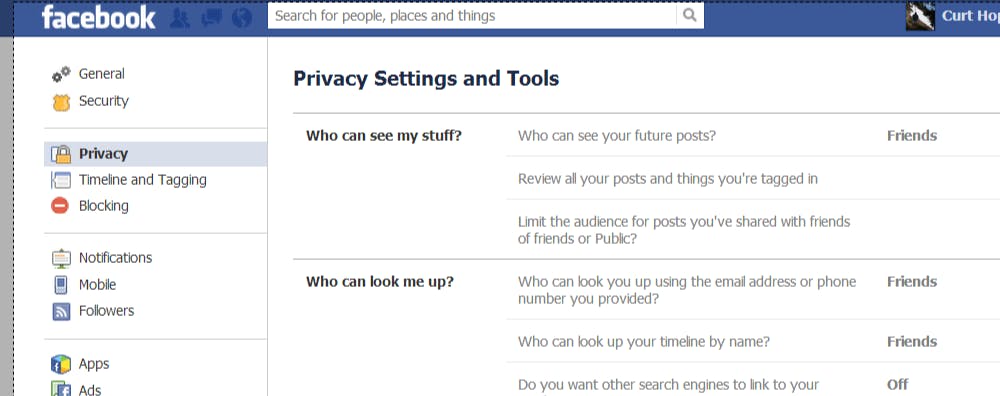

Image via Facebook

What makes sites like Facebook and Twitter dangerous in terms of our security is our tendency to gibber on as though we were among friends, instead of among “friends.” We often give out contextualizing information that can lead to our being identified, even when we’re being careful. When we’re not being careful, it’s even worse. Spouses’ names, cities of residence, even the street we live on might be mentioned, allowing ne’er-do-wells to perpetrate social hacks based on information tailored to specific targets, a type of scam known as “spearphishing.”

The problem with trying to manage security on a social network is both the fact of it being a third party tool and the fact that you, as the saying goes, are the product, not the product’s owner. Still, there are several options.

Don’t use social networks. They’re a mess and the social milieu is one of laxity and oversharing. The companies that run them seem to change privacy policies constantly, making it difficult to keep on top of. Facebook in particular is notorious for this.

Clamp down. Find the maximal security settings for any social network you’re using and employ them. With Twitter, make your account private, so only those you allow can follow you. In Facebook, choose sharing with your “friends” as your default, across-the-board selection.

Don’t share anything of a personal nature. Don’t tell people that you and your wife Lydia drove from your house on Eastern Drive downtown to dine at Flan, as you do every Tuesday night. Don’t post your email address, your phone number, the name of your child’s school. Don’t tell thieves, hackers and creeps the information they will need to screw you to the wall. And understand, they don’t need much.

Technologist Griffin Boyce told the Daily Dot that hell is other people, even if they’re people you know and mean to communicate with.

“When chatting/emailing you can’t always trust the other person to not pass along your conversation,” Boyce said. “The human element is always the biggest. In a lot of ways, your security is reliant on the other person’s security as well. This is pretty obvious when talking to people in other countries (where they might be surveilled), but it’s also important to consider when talking to someone locally.”

The Internet is just awful

The only way to guarantee 100% digital security is to stay analog. A security specialist said, years ago when email and blogging were the main avenues we traveled to speak to one another online, that given time enough and money, anyone could be hacked. An organization with enough of both—especially, though not solely, a governmental one—could, if they were willing to spend and work until it was done, get their hands on your junk.

Photo by Liwi S./Flickr

That hasn’t changed. If anything, there are more avenues than ever to your private information. The default level of security online is none.

But most of us are unwilling to become digital apostates. So what we must do is decide how much time and trouble we are willing to go to in order to reach what we believe to be an adequate level of security for our personal needs, that of our families and of our companies.

And probably, we can reach that level. But it’s something that comes from conscious decisions and actions. At the very least, promise us you won’t leave your doodads lying around and that you’ll slap a password on anywhere one will go. Will you do that? We’re worried about you.

Illustration via Bigstock