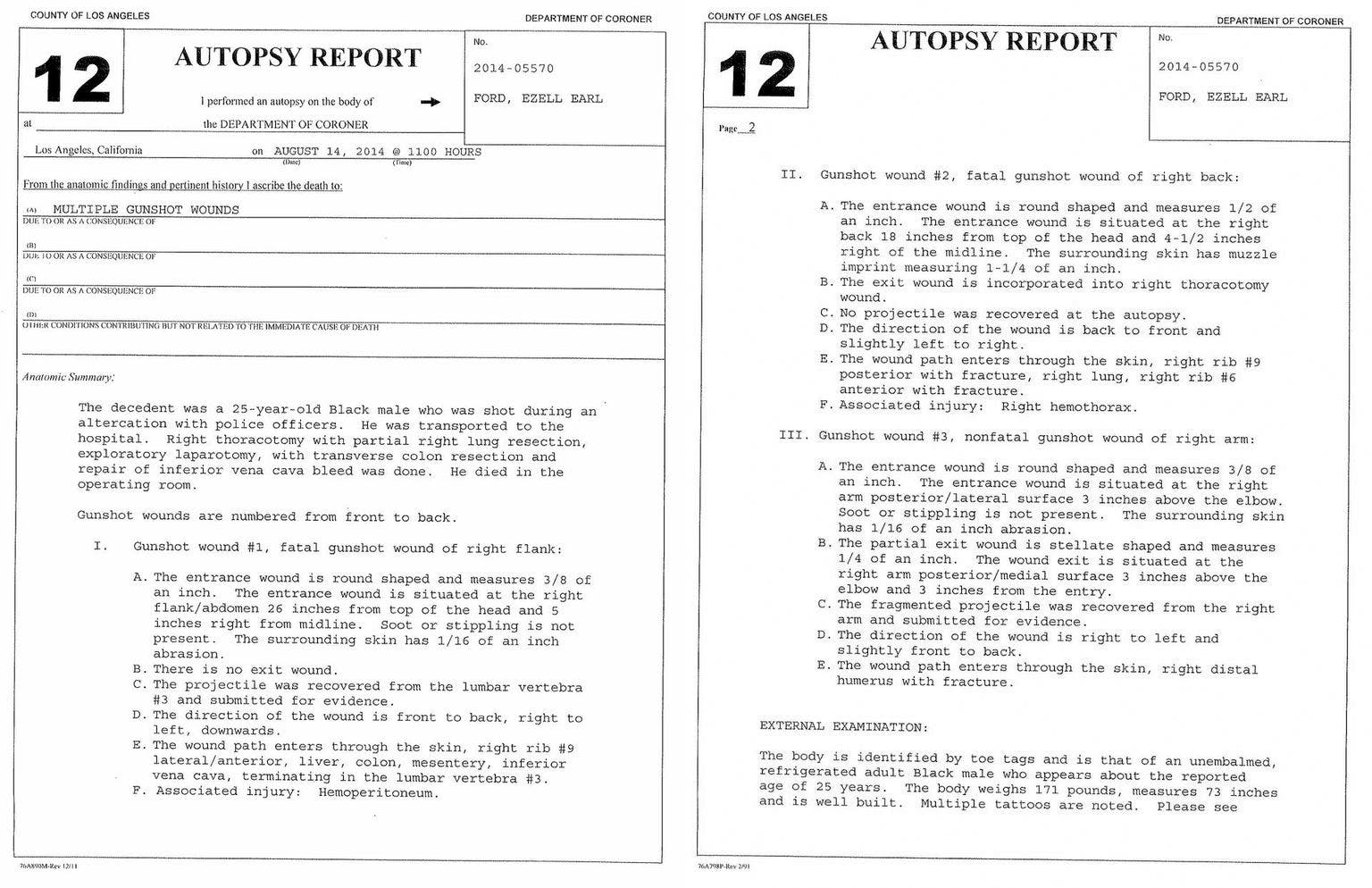

Ezell Ford was killed by a bullet in his back, fired from a gun pressed directly up against his skin.

This is the primary finding of an autopsy report on the August homicide of Ford at the hands of Los Angeles police officers. The report was released by the County Medical Examiner-Coroner on December 29, following calls from citizens incensed by its months-long delay.

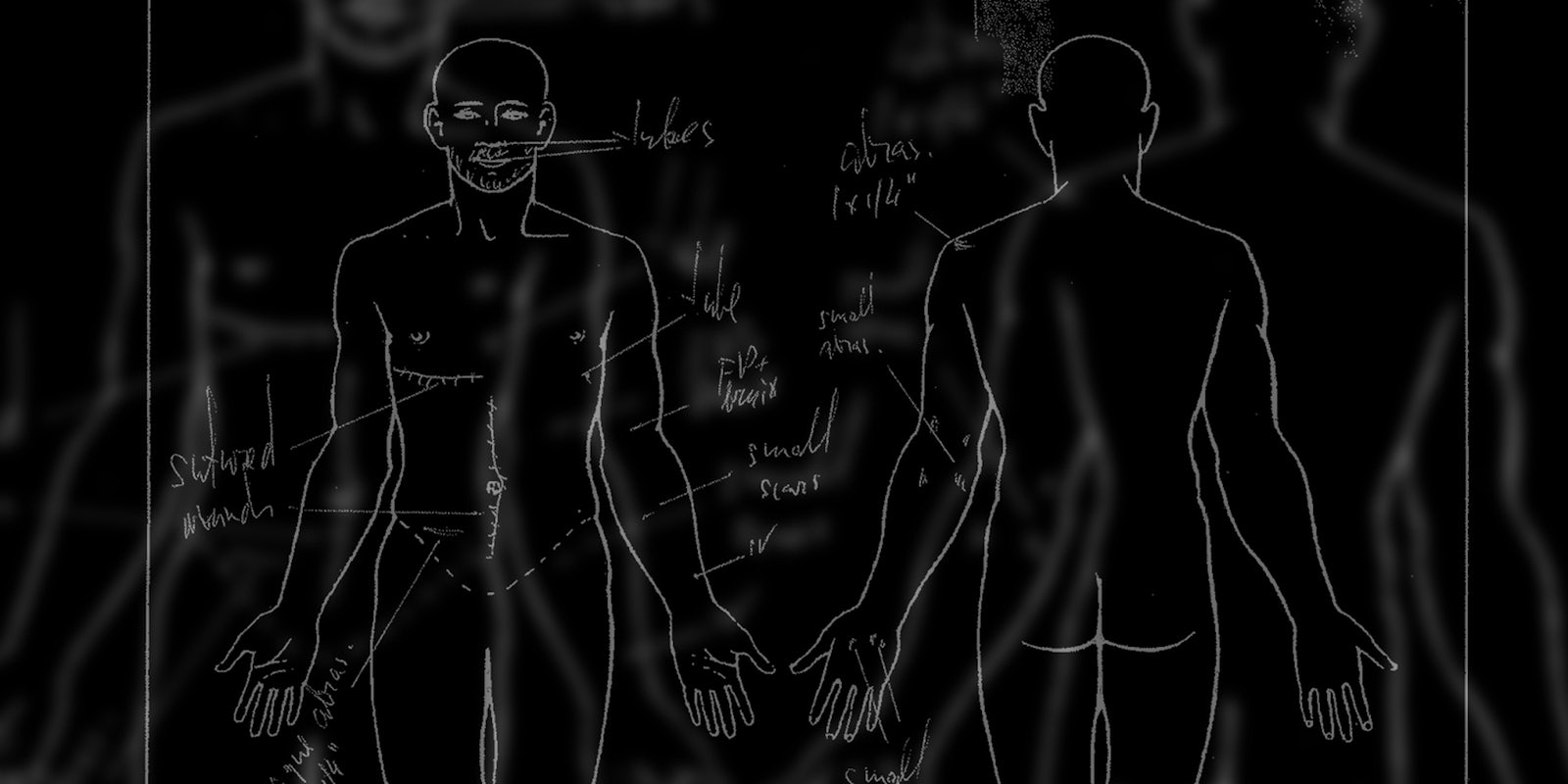

The report found that the 25-year-old black man was shot twice in the back, and once in his right arm. He was unarmed. The fatal shot—to the right side of his back—left an imprint of the gun’s muzzle, indicating it had been pressed directly against Ford’s skin when the police officer pulled the trigger. After firing three shots, officers then handcuffed him, bleeding on the ground until he was transported to California Hospital Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead at 10:10pm.

Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck stated Monday that the autopsy was consistent with testimony made by the involved officers, who have not yet been charged with a crime, pending a police investigation. But the parents of the deceased man charged that the cops who killed their son were getting away with murder.

Ford’s name became a rallying cry after he was gunned down on August 11, just two days after Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, Mo. But despite months of demonstrations surging alongside nationwide manifestations of anger against “systemic, institutional racism in police forces throughout our country”—the absence of accountability is pouring salt on open wounds.

It’s unclear why Officers Sharlton Wampler and Antonio Villegas stopped Ezell in the first place. He was walking down the sidewalk on 65th Street in the Florence neighborhood of Los Angeles when officers approached him to conduct what police called an “investigative stop.” Bystander and police accounts agree that Ezell walked away from the officers, but that’s where the agreement ends.

Los Angeles Police said at a press conference three days after the shooting, “when the officers got closer and attempted to stop the individual, the individual turned, grabbed one of the officers, and a struggle ensued. During the struggle, they fell to the ground and the individual attempted to remove the officer’s handgun from its holster.”

But that’s not how witnesses in the neighborhood saw it. Bystanders interviewed on the scene after the shooting said that Ford was needlessly shot in the back while lying on the ground.

“They executed him. They laid him out and for whatever reason, they shot him in the back, knowing, mentally, he has complications,” another witness told reporters at the scene of the shooting. “Every officer in this area, from the Newton Division, knows that this child has mental problems.”

Ford had been diagnosed from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, and was taking medication prescribed for those conditions, his mother, Tritobia Ford, told local news station KTLA. Neighbors said he was a calm, cool young man who had never displayed violent behavior, and wasn’t involved in a gang, as police statements insinuated immediately following the shooting.

“He was such a nice kid,” family friend Michael Anderson said. “He was a little slow, but he didn’t bother nobody.” Witnesses said a swarm of cops pushed them back, ambulances were prevented from reaching him while he lay bleeding on the pavement. “They let Ezell die,” another witness said.

Police said that Ford shriveled up into crouching position between two cars, and when the cops approached the frightened man, he tackled one of them and reached for his gun. It was then that the other officer drew his weapon and fired, while the other produced his backup gun, reached around Ford’s back and shot him in the back.

“He didn’t fight back. He couldn’t have fought back,” one of Ezell’s neighbors said in an interview in late August. He was on the ground the while time. Two big, healthy cops on top of a skinny guy. They could have shot him with a Taser gun.”

“He was just walking up the street, and they jumped out on him with the guns drawn. He was scared. He said, ‘I don’t have nothing,’ and put his hands up like that, and they wrestled him to the ground. A shot went off—and then they shot him again. And then another two seconds later, they shot him again. Three times.”

Another eyewitness said they heard one of the officers scream out “shoot him!” before firing the deadly bullets.

The release of the autopsy report suggests that investigations may be coming to a close, though charges being brought against Officers Wampler and Villegas an unlikely outcome. “We have time periods by which we intend to complete these investigations, and if we get to those periods, we will release the autopsy,” the Los Angeles police chief said at a mid-November press conference.

Police had ordered a “security hold” on releasing the report because investigators said they were having a hard time finding witnesses willing to come forward and speak to them, hampering their efforts. “We want witness statements to be as untainted as possible. That is why we have withheld the autopsy,” LAPD Chief Charlie Beck said at a press conference in November. “There are people out there we believe who may have seen what happened, and we will rely on them to help us forward with this case.”

Chief Beck conceded that the LAPD suffered a lack of public trust, making witnesses hesitant to speak to investigators. He pleaded for anyone with information to come forward. “If people are reluctant to talk to the Los Angeles Police Department, I understand that,” he said, stressing that the department had made progress at healing deep-seated resentment of police since the brutal days of the 1992 riots, when entire city blocks burned after news cameras caught police ruthlessly beating Rodney King after a traffic stop.

Residents of Ford’s neighborhood on West 65th Street, however, said that individuals who had come forward weren’t met with open arms, but rather, with deaf ears.

“People are in fear of the police department,” a man who lives on the block near Ford’s shooting told reporters in August. “I told everybody in the neighborhood I saw it. I told the cops, I put it on my Facebook page, I even told Ezell’s dad I saw it. They know I know what happened because they know I live right there,” he said.

Ford’s parents are suing the city of Los Angeles and the police department for $75 million on the basis that police had no reason to confront their son, and were targeting him for his race.

The family also said in their complaint that the officers could observe that Ford was mentally ill, and instead of responding in a sensitive manner, they “acted with callous indifference.”

“Policing in America is at a crossroads. There is mistrust of law enforcement in some communities,” Chief Beck acknowledged. After 2014’s bloody summer, where four black men were killed by police in the span of one month, Ezell Ford’s was the local case that connected Los Angeles to a national uprising against police brutality following news of officers exonerated in Ferguson and New York in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, respectively. It is but one page in a tome of stories where the justice system places a cop’s word against the dead who can’t speak for themselves, and living who feel their voices have not been heard.

Photo via Los Angeles County (PD) | Remix by Jason Reed