For the first time this week, the American public gained access to one of federal law enforcement’s most powerful and secretive tools: a National Security Letter.

Publication of the NSL comes more than a decade after the Federal Bureau of Investigation delivered it to Calyx Internet Access in 2004 and, in doing so, demanded troves of information on customers in legally mandated secrecy and without a warrant or the involvement of a judge.

Nicholas Merrill, who was president of Calyx in 2004, revealed the full scope of the letters after a legal battle that began with a uncertain visit to the American Civil Liberties Union.

“Nick wasn’t sure why the FBI was demanding the information, but he knew a little about the subscriber the FBI was apparently investigating, and he doubted that the investigation was a legitimate one,” director of the ACLU Center for Democracy Jameel Jaffer explained in a recent blog post. “He wondered how it was possible that the FBI could demand such sensitive information without the involvement of any judge. And he wondered whether he was violating the gag order simply by asking us for advice.”

Today my #NationalSecurityLetter gag order is gone after over 11 years of litigation. I hope others who get NSLs find ways to challenge them

— Nicholas Merrill (@nickcalyx) November 30, 2015

I risked my freedom to speak out about my #NationalSecurityLetter because I feel strongly about the need to protect #privacy and #freespeech

— Nicholas Merrill (@nickcalyx) November 30, 2015

The @FBI shouldn’t be allowed to demand #private customer records without any suspicion of wrongdoing or without any approval from a court.

— Nicholas Merrill (@nickcalyx) November 30, 2015

An unredacted court decision shows that the FBI ordered Calyx Internet Access to reveal all physical mail addresses, email addresses, Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, telephone and billing records, and anything else that could be an “electronic communications transactional record” of one customer.

The FBI did not order the revealing of the content of emails themselves.

“[A]n unlimited government warrant to conceal, effectively a form of secrecy per se, has no place in our open society” -Judge Victor Marrero

— Nicholas Merrill (@nickcalyx) November 30, 2015

A Justice Department inspector general report from 2007 showed the FBI issued 143,074 NSLs between 2003 and 2005, up roughly 1,650 percent from the approximately 8,500 NSLs issued before the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Over the last decade, public debates over surveillance and the Patriot Act, which fueled the major increase in NSL usage, drove Merrill forward in the legal battle.

“If I hadn’t been under a gag order, I would have contacted members of Congress to discuss my experiences and to advocate changes in the law,” he wrote in an anonymous Washington Post op-ed in 2007. “The inspector general’s report confirms that Congress lacked a complete picture of the problem during a critical time: Even though the NSL statute requires the director of the FBI to fully inform members of the House and Senate about all requests issued under the statute, the FBI significantly underrepresented the number of NSL requests in 2003, 2004 and 2005, according to the report.”

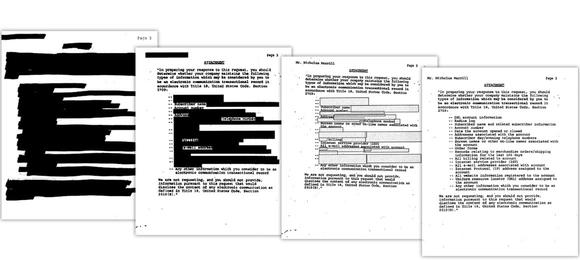

The NSL attachment Merrill got from the FBI, in varying stages of redaction https://t.co/pM9wAbKs1Y @nickcalyx pic.twitter.com/wIhAOugqFX

— ACLU (@ACLU) December 1, 2015

“I recognize that there may sometimes be a need for secrecy in certain national security investigations,” Merrill wrote. “But I’ve now been under a broad gag order for three years, and other NSL recipients have been silenced for even longer. At some point—a point we passed long ago—the secrecy itself becomes a threat to our democracy.”

H/T ACLU | Illustration by Max Fleishman