Because the U.S. government is so bad at counting how many Americans are killed by police officers each year, a handful of reporters at the Guardian have decided to do it themselves.

The project, aptly named The Counted, is the brainchild of Katharine Viner, the Guardian’s former U.S. chief, who took the reins from Alan Rusbridger last week to become the first woman to run the newspaper in its 194-year history.

Following the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., last fall, a number of similar projects sprung up, such as killedbypolice.com, a site that relies solely on local news reports to amass its data. Fatal Encounters, a crowdfunded project documenting police-involved homicides dates back to 2000, according to the website.

“Some were being violent toward other people, some of them were shooting at police themselves.”

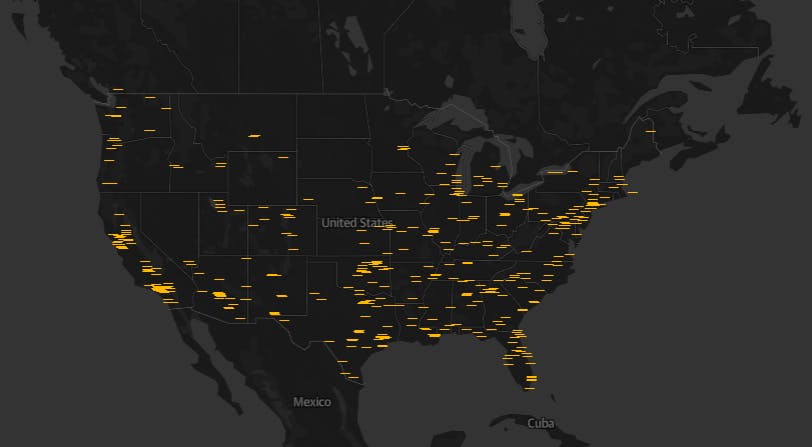

In a phone interview, Jon Swaine, the lead reporter on The Counted, said the project’s predecessors were an inspiration, but the Guardian is hoping to compliment their work with more traditional investigative reporting. In addition to collecting data from local news reports, the journalists have been placing calls to police departments, coroners offices, attorneys, and the families of victims, in an attempt to gather the most complete, accurate database online. The team is also accepted tips from the public. They’ve documented 464 police-involved deaths this year so far.

33% of black people killed by police so far this year were unarmed, Guardian analysis shows http://t.co/7auFxxcfGe

— The Counted (@thecounted) June 1, 2015

Having a team of dedicated journalists has paid off. Swaine, who’s been at the Guardian for about 15 months and before that wrote for the London Daily Telegraph, said his team has identified the names of people on existing lists that aren’t actually dead. They’ve also discovered at least five previously unreported deaths. “The open-source sites hadn’t got them, the police departments hadn’t released them, until we chased them and made records requests, or made a couple of phone calls or a couple of emails, just like reporters always have done,” Swaine told the Daily Dot.

Swaine’s team, which includes Guardian reporter Oliver Laughland and researcher Jamiles Lartey, a recent New York University graduate, is adamant about including all deaths that occur at the hands of police, whether they’re deemed justifiable or not. In some cases, he says, it would be hard argue that those killed were “doing good in the last moments of their lives.”

“Some were being violent toward other people, some of them were shooting at police themselves,” said Swaine. “But we just think it’s important to have the information about even those cases to be public, and for us to tell the full story of what happened with them, and let the readers make up their own minds about what is justified.”

U.S. lawmakers have made several attempts to improve the way the federal government collects and reports information about police-involved deaths. The Death In Custody Act, for example, passed in 2000, but failed to deliver because the reporting process was entirely voluntary, and many states simply chose not to participate. The law expired in 2006, but it was resurrected this year.

Ironically, Michael Brown’s death may not be covered under the law since, as its name suggests, it only requires law enforcement agencies to report deaths that occur when the suspect is in police custody. Like many of the people counted by the Guardian, he was killed before he could be arrested.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation also produces an annual report, but it only collects information voluntarily provided on “justified homicides,” and is widely regarded by experts as inaccurate.

Each case reported by Swaine’s team is denoted with a status that indicates if the homicide has been ruled justified, if an officer has been charged, or if the incident is still under investigation. “We just think it’s worth getting all of these in one place, so we can explain how and why people died,” Swaine said. Just by randomly clicking through a dozen or so cases, even those from when the database begins in January 2015, you can see that most are still under investigation.

Asked if one purpose behind the project was to incite further demands that the federal government improve the way it reports police-involved homicides, Swaine pointed to several petitions already circulating by organizations, such as the American Civil Liberties Union and Change.org, to which the project is referring readers.

“We’re not starting a petition ourselves,” said Swaine, “but we do as an organization—and we say this in the About page of the database—editorially advocate for the reporting of this information.”

Photo by Tony Webster/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)