If you had the app open at just the right time, it was possible to pinpoint the precise moment that Uber and Lyft left Austin. It was two days after voters in the Texas capitol rejected a ballot measure that would have reversed a law passed by city council that requires ride-hailing services to fingerprint their drivers.

Proposition 1 failed on Saturday. Even though the fingerprinting requirements don’t go into effect until next February, the reverberations were felt almost immediately. On Monday morning, Uber and Lyft went dark in Austin, just as they had threatened to, and all the little cartoon cars representing all of the drivers cruising the streets vanished in a flash.

https://twitter.com/ashleyjjennings/status/729644744716877826

Contrary to the dire prognostications of Prop 1’s backers, these departures don’t mean the end of ride-sharing. Lyft and Uber may have left town, but there is a local alternative.

Get Me is an upstart ride-hailing company in the model of the multibillion dollar Silicon Valley darlings that was given a rare opportunity. With Uber and Lyft suddenly out of the picture, Get Me now has access to a mature market of people in Austin looking for rides and a lot of former Uber and Lyft drivers with free time on their hands.

But what does anyone really know about Get Me, and can the relatively unknown startup fill the hole left by Uber and Lyft’s sudden departure?

Get Me started in Dallas in mid-2014 with an idea to create a single, unified platform that combined the ride-hailing of Uber with the on-demand delivery of Postmates or TaskRabbit. Users can either select “Get Me Something” or “Get Me Somewhere,” and the company’s network of drivers would respond accordingly. The company moved its headquarters to Austin last year and has rolled out service there, Houston, San Antonio, and Las Vegas.

“This was not about fingerprinting. It’s way bigger than that.”

When the Daily Dot profiled Get Me in February, the company had about 10,000 drivers signed up across every city in which it operates. That’s a lot of vehicles, to be sure, but it’s only about one-quarter of what Lyft and Uber have in San Francisco alone. It’s still very much a small player against a pair of tech behemoths. What separates Get Me from its competitors—and what’s behind its sudden opportunity in Austin—is the company’s public willingness to play by whatever rules government regulators put in place without major complaints.

Prop 1 was ostensibly about fingerprinting, but the real issue is something much more fundamental: It was about the ability of a city take away the most important advantage Uber and Lyft have over the taxi fleets that preceded them—the ability to effectively set their own rules.

Since the Great Depression, when economic turmoil sent throngs of people with cars out into the streets to become gypsy cab drivers, cabs have been tightly regulated by municipalities around the county. Governments set how much cabs could charge customers, what levels of insurance they needed to carry, how many cars could be on the road, and what safety precautions they had to follow. Complying with these rules make the process of driving a cab far more expensive and the process of ordering a cab far less convenient. The core innovation of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft was using non-professional drivers in their own cars to avoid these regulations—a throwback to the era, nearly a century ago, before all those rules were imposed in the first place.

In Austin, and many other locations across the globe, these companies basically will these advantages into being. Lyft and Uber first began operating in Austin at a time when city rules directly prohibited the type of service they were brazenly offering. As the city set up sting operations to catch offenders and impound their vehicles, the cost of which was reimbursed in full by Lyft and Uber, drivers would tell passengers to sit in the front seat as to not tip off police on the hunt for ride-hailing scofflaws. As this lawbreaking was going on, the companies waged a simultaneous publicity campaign to convince the city government to make what they were already doing legal—and it worked.

Ride-hailing was eventually legalized in Austin on a temporary basis. Last December, the city council passed an ordinance imposing a new set of rules, most notably mandating fingerprint-based background checks on drivers. The companies were not happy. Under the umbrella of an industry group called Ridesharing Works, the companies collected over 65,000 signatures to get a measure on the ballot overturning the ordinance.

The $8 million campaign Ridesharing Works waged to convince Austinites to vote for Prop 1 was the most expensive of any election in city history and outspent its opponents 80-to-1. Ridesharing Works paid celebrities like Taylor Kitsch, best known for playing Tim Riggins in the Texas high school football drama Friday Night Lights, and former Austin Mayor Lee Leffingwell to campaign for their cause. They argued ride-hailing decreased drunk driving and that fingerprint checks were discriminatory against over-policed minority communities. Mostly, they just threatened to leave.

It was a tough sell. These tactics reeked of bullying, and the overwhelming majority of civic groups lined up against Prop 1.

Mmmhmmm. #VoteAgainstProp1 #TNC #atx #ATXCouncil #Uber #Lyft pic.twitter.com/LnDHOWB93i

— Bobby Levinski (@BobbyLevinski) April 21, 2016

Get Me took a different approach altogether. Chief Experience Officer Jonathan Laramy insisted that the company initially had an eye on rolling out service in Austin but made the decision to wait until doing so was entirely legal. Get Me also largely stayed out of the Prop 1 fight because the essence of the fight was over ride-hailing companies’ ability to effectively set their own rules over what local governments may prefer, which isn’t how the firm’s leadership believes that relationship should work. “We stayed out of all the political stuff,” Laramy said. “This was not about fingerprinting. It’s way bigger than that.”

“All in all my first couple experiences with Get Me were so negative I deleted the app.”

Among ride-hailing companies, Get Me was an anomaly because it supported fingerprint background checks from the beginning, arguing those policies were crucial elements of keeping people safe. While Lyft and Uber insisted they would take off if things didn’t go their way, Get Me held from the beginning that it was going to stay in Austin regardless of Prop 1’s fate.

“We as a business must follow the rules or legislation that the cities or towns that we go into, just if we were a restaurant business there are city ordinances that must be followed,” a Get Me spokesperson wrote in a recent Facebook post.

There’s some precedent to suggest Uber and Lyft’s eventual return to Austin may be imminent. When Uber was unable to strike an acceptable operating agreement with the city of San Antonio last year, it halted operations, only to come back six months later after obtaining more favorable terms from the city.

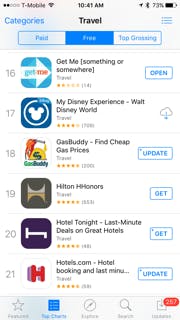

In the meantime, Get Me essentially has Austin’s ride-hailing market all to itself. According to an analysis by social media analytics firm Spredfast, tweets in the Austin area about the company jumped 281 percent in the days surrounding the vote over the week prior. The Get Me app jumped to near the top of the charts for travel apps in the iOS app store, largely due to an influx of former Lyft and Uber drivers in Austin flocking to try the app en masse.

Get Me reports that, in the 72 hours after Uber and Lyft left Austin, the company’s app was downloaded over 30,000 times.

One Get Me driver, who had been driving for the company since January, in addition to Uber and Lyft, said that, while driving on Tuesday, he saw by far the most ride requests he had ever seen on the app.

“Get Me is definitely much smaller than Uber and Lyft, but they’re getting more popular by the day with drivers,” explained Harry Campbell, who operates a blog and podcast for ride-hailing drivers called The Rideshare Guy. “The problem with a lot of these smaller or more niche rideshare services is that there just aren’t enough passengers to make them worthwhile for drivers. But Get Me provides essentially the exact same service as Uber and Lyft, and will likely see a huge spike in adoption with Uber and Lyft out of the picture.

“Although passengers will have to download a new app, they will probably find that their experience with Get Me is very comparable to Uber and Lyft,” Campbell continued. “In fact, every Get Me driver that I’ve talked to also drives for Uber or Lyft, so they’ll essentially be getting the same rides but from a different app.”

According to people in Austin who have tried using Get Me in place of Uber or Lyft, however, the experience has often failed to meet expectations. For one thing, the service is far more expansive, as one local Twitter user demonstrated in a direct comparison of a trip from a park in downtown Austin to the airport.

Maybe background checks do increase pricing… #Prop1 #Prop1ATX @GetMe_USA = $28@lyft = $14.86@Uber = $11.79 pic.twitter.com/Q2BEHdQRfB

— Edward Bloat (@edwardbloat) May 8, 2016

Austin resident Jennifer Harris tried using it the night of the election and immediately got sticker shock. The approximately three-mile ride from downtown to her home in Hyde Park neighborhood usually cost about $4 on UberPool. Get Me’s estimate was around $20.

Laramy said that the reason for the Get Me’s higher cost was its desire to give more money to drivers, as a way to attract more of them to the platform. “We understand that the driver is the asset. Without the driver you’re nothing,” he explained, noting the company plans on rolling out marketing in the coming weeks advertising discount codes for riders that, he insists, will bring Get Me’s effective prices in line with what Lyft and Uber riders were used to without cutting driver pay.

Lyft and Uber drivers across the country have complained that the companies’ have been consistently cutting rates, which makes driving a decidedly less attractive proposition than what’s advertised. Surinder Dhillon, a San Francisco taxi driver who quit to drive for Uber and Lyft thinking he could make more money, quickly hopped back in his cab after realizing his take-home pay on the ride-hailing platforms was under $10 an hour after paying for expenses like gas and vehicle maintenance.

Get Me’s price wasn’t the only issue, though. There were also reports of problems with the technology. “I tried to download the app yesterday, but the software didn’t work with my phone,” said Michael Agresta, who calls himself a proud “No on Prop 1” guy. “It kept directing me to turn on location services, but they were on. It kept popping up with that notification, so I actually had to delete the app to make it shut up. Not ready for prime time, looks like.”

The most “dodgy” aspect of the company is likely the insistence of its CEO to remain anonymous.

Austin resident Justin Key reported a similar experience with the app the morning after Uber and Lyft abandoned the city. Key and his wife waited for almost 15 minutes without being connected to a driver, and eventually the app automatically canceled the request—but not before putting a $25 pre-authorization charge on his credit card without warning him beforehand. “All in all my first couple experiences with Get Me were so negative I deleted the app. Neither one of us have tried using it since, but may again in the future if we hear of other people having positive experiences,” he said. “Using ride sharing was a regular part of our daily lives, so not having that as a viable option really had a negative impact on us as a one-car family.”

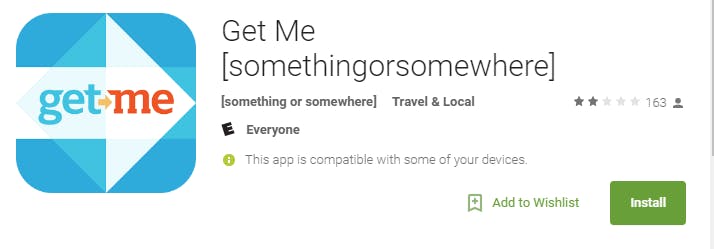

These experiences aren’t uncommon. On the Google app store, Get Me only has a two stars out of five, with the overwhelming majority of users giving it lowest possible rating.

Compared to Uber and Lyft, which have used massive investments from venture capital firms to build slick, infrastructures, Get Me clearly has a hard row to hoe.

There were also frustrations around the company’s recent efforts to recruit former Uber and Lyft drivers. Get Me sent an email to over 500 potential drivers containing information about the onboarding process. Not only were all the email addresses not entered into the bcc field, meaning everyone on the email blast could see everyone else’s email address, but the actual onboarding process was being held “by the airport right behind the Shell gas station.”

It didn’t exactly inspire confidence in the organization’s professionalism. A post on the company’s Facebook page asserted that the spot, which was admittedly “dodgy,” was chosen because it was an open location that was easy get into and out of. “As we said,” the post read, “we’re still listening and learning.”

However, the most “dodgy” aspect of the company is likely the insistence of its CEO to remain anonymous. While the rest of Get Me’s leadership team is listed and pictured on the company’s website, the person in charge remains a mystery.

“I’m not going to mention my name, my past or anything like that, I parked my ego long ago and don’t feel the need to massage that or look for any kind of validation or ‘pat on the back’ this is the true story of how, with my awesome team, we plan to roll out our company from local to global in 6 months – and you are all welcome to come along for the ride,” the CEO wrote in a blog post on Medium that describes the author as a “Serial Entrepreneur & Visionary.”

Laramy insisted that the mystery behind the CEO’s identity is nothing to worry about. He or she will reveal themselves eventually and is mainly staying behind the scenes because they are also working on other projects. “The CEO is not involved in the taxi industry. It’s nobody in the government. It’s nobody with another ride-sharing company,” he said, “When they…are announced, whether that’s next week or in two months, I don’t think it’s going to change anybody’s opinion of if they use us. We’ve never understood why this is a thing that people are so curious about.”

Nevertheless, all of these things together paint a picture of a young company thrust into the limelight before it was entirely prepared to carry the full weight of ride-hailing in Austin on its shoulders.

“Being pushed into the spotlight as a start-up is never a comfortable feeling. You are typically under scrutiny from users that have been utilizing other companies technology that has been well established, had millions of dollars and millions of work hours behind it,” reads another company Facebook that lists a slate of planned features, such as female passengers being able to request female drivers, that have been put on the back-burner as the company simply tries to meet demand. “Once you are under the microscope, all your ‘flaws’ are exposed.”

Get Me may be the highest-profile app-based option left in the city, but it’s not the only one. Companies Wingz and zTrip let customers book trips to the airport. Bill George, president of zTrip’s taxi division, told the Daily Dot in an email that the company is increasing the size of its fleet of taxis and towncars by 500 in light of repercussions of last weekend’s vote.

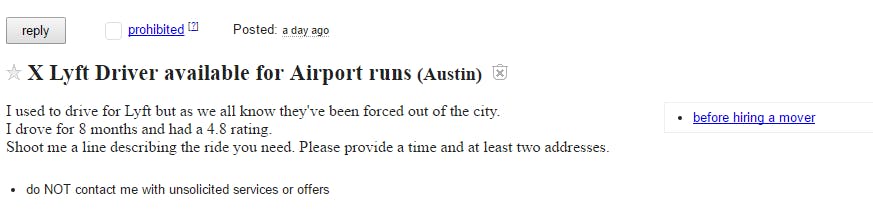

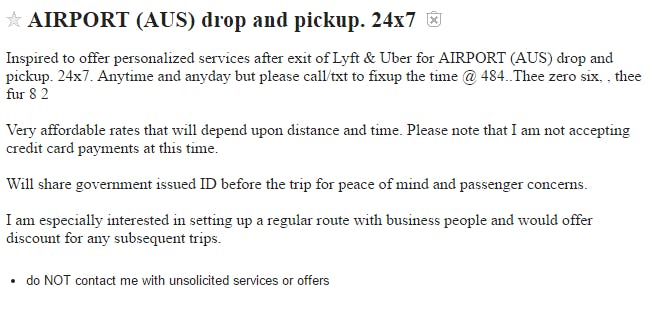

For their part, some former Lyft and Uber drivers are just going underground and becoming gypsy cabs unaffiliated with any transportation network company. In the days since Lyft and Uber skipped town, ads like these have begun popping up on Craigslist.

Sam, a former Lyft driver who made one of those Craigslist posts, said he would be willing to try any of these new apps to see if they pay better, but he already turned down requests from people asking him to be their daily chauffeur to and from work. “[I’m] not going to hang out downtown and pick up drunks [because it’s not really worth it to do small rides,” he explained in an email, but he added that he did like doing the occasional airport run.

“I’ve been told by several riders that they’d rather buy a car then start using taxis,” he added, which is likely not encouraging for Hailacab Austin, an app that does pretty much exactly what its name implies.

“It’s like we’re trying to plan a barbecue when there’s a really good chance it’s going to storm.”

There are efforts to bring in new ride-hailing options into the city. One is a project called Warp Ridesharing that’s currently looking for funding on Kickstarter. Warp founder Ryan Brown explained that Warp would work like other ride-hailing company about 25 percent of the profits would be reinvested in the local community through donations to nonprofits by a vote of the users of its platform.

Brown had been working on the app for while, but Uber and Lyft leaving town kicked the project into overdrive. Brown knows that he has to work fast. Uber and Lyft could strike a deal with the city and come back to Austin, like what happened in San Antonio, robbing Warp of its opportunity to grab market share without the big guys in the room.

“It’s like we’re trying to plan a barbecue when there’s a really good chance it’s going to storm,” he said. “We’re still planning the barbecue just hoping it’s not going to storm, but it keeps looking like it’s going to be a really bad storm…but I’m just going to push through this until it gets crushed.”

For its part, Get Me already has a significant head start. Despite some of its setbacks with customers, Get Me’s position is enviable. It has a critical mass of drivers who know how the system works eager to sign up a pool of passengers, already comfortable with hopping into a stranger’s car, looking for rides.

“We never wanted people to take the ball and go home because they’re sore losers,” Laramy said. “This isn’t about Get Me flying down from the sky in its chariot to rescue Austin.”

Instead, it’s more like the the company just happened to discover this chariot sitting in its path, suddenly and unexpectedly unused. All the company has to do is make sure the reigns don’t slip from its grasp.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include Get Me’s recent download totals.