Speaking at the South By Southwest Interactive conference in Austin, Texas, earlier this week, Dan Wagner attempted to do the impossible: explain the rapid political rise of Donald Trump to a bunch of tech-savvy Millennials.

Wagner, the chief analytics officer for President Barack Obama‘s 2012 reelection campaign and founder of Chicago-based data science advisory firm Civis Analytics, argued that everything the SXSW audience needed to know to about how Trump bucked pundits’ predictions, forced out the GOP’s establishment candidates, and rose to the top of the Republican presidential pack is contained in a single viral video.

The video, shot in early February, shows employees of air conditioner manufacturer Carrier in Indianapolis angrily reacting to an announcement that the entire plant would be moved to Monterrey, Mexico, leading to the eventual elimination of most of their jobs.

“Relocating our operations to Monterrey will allows us to maintain high levels of product quality at competitive prices and continue to serve the extremely price-sensitive marketplace,” said Carrier President Chris Nelson over a chorus of boos. “I want to be clear. This is strictly a business decision.”

“Yeah,” replied a frustrated worker, “fuck you.”

For Wagner, this video, which received more than 3.5 million views in a month, sits at the core of the success of Trump’s candidacy.

When Wagner polled the South By Southwest audience about how many of them had previously seen the clip, about one-quarter raised their hands. The response exposed a key element of the surprise around Trump’s rise: The posh urbanites that, generally speaking, make up the SXSW crowd—and, one could argue, the mainstream media—are a far cry away from the struggling, frustrated Americans who count themselves among Trump’s supporters.

“Trump talks about this video in almost every speech,” Wagner continued, asserting that the percentage of Trump supporters who have likely seen the video is significantly higher that in the room.

There are two important things about the video in how it relates to Trump.

First, the content. Ideologically, Trump is not a typical conservative. The standard conservative orthodoxy is one that holds the free flow of labor and capital across international lines as a near-universal positive. Trump, at least in his most recent incarnation, is not a free-trader in any sense of the word. He advocates protectionism at home and has openly called for actions that would almost certainly incite trade wars with key U.S. trading partners like China and Mexico.

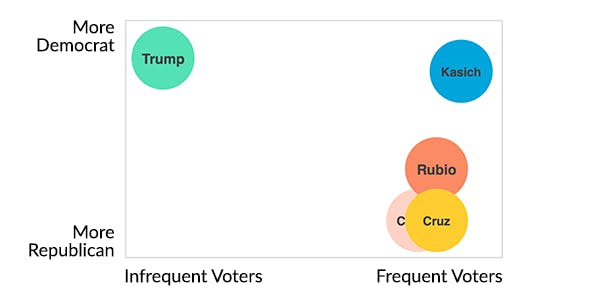

As a result, the profile of the average Trump supporter is very different than the backers of other 2016 GOP candidates. When Wagner ran the numbers on the supporter bases of five current and former Republican presidential hopefuls—Trump, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson, and Ohio Gov. John Kasich—he noticed an interesting divide when he plotted their position on the ideological spectrum against how frequently they voted in prior elections.

Rubio, Carson, and Cruz are all clustered in the lower right-hand corner of the chart, meaning they were all chasing (and, therefore, splitting) the same group of voters: extremely engaged political conservatives. Kasich nabbed the frequent voters in the party who are more moderate, a group that’s gradually withering away as the party polarizes.

“Trump is representing a different class of people than everybody else,” said Wagner. “If you look at the results so far, he’s doing much better in open primaries than in caucuses.”

Wagner’s argument is that, while the real-estate heir and reality-TV star’s support from hard-right white supremacists and neo-Nazis is thoroughly documented, Trump’s rise is largely a result of activating the so-called “silent majority,” Americans who would paint themselves as relatively moderate—if they paid any attention to politics at all, besides weighing in with apathy and disgust. Trump’s message targets a base of potential Republican voters that other campaigns typically ignore for the simple reason that they don’t usually vote.

Contrast Trump’s message with that of former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney. The GOP’s 2012 presidential nominee never bashed free trade during his failed run, and he sharply criticized Trump’s economic isolationism in a recent speech. Romney’s position on trade isn’t simply a reflection of his personal worldview; it also speaks to the traditional Republican base’s similar position on trade. By ignoring this orthodoxy, Trump is casting his line into and entirely different, and significantly less crowded, pool of American voters.

“At first, you see news reports about Trump, and he seems crazy,” Wagner said of a hypothetical American voter. “But then someone who you trust shares the video of jobs shipping to Mexico in the context of Trump, and it resonates with you.”

The word “trust” is crucial here—the second aspect of why this video is important. Before the dominance of social media, what we now call the mainstream media—broadcast and cable news, and institutions like the New York Times and Washington post—served as unchallenged gatekeepers of our information. Not any more.

For Trump, that’s key: Our trust has shifted from institutions to individuals.

Much hay has been made about the American public’s loss of trust in mainstream media. Gallup found that, between 1999 and 2015, there’s been a 15 percent decline in the number of people who have a great deal of trust “in the mass media … when it comes to reporting the news fully, accurately and fairly.”

While some of that certainly has to do with the conduct of media itself, it’s also a function of people no longer needing those media institutions to act a distribution mechanism in an age when social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter allow for direct transmission of content directly from one individual to another.

Something else is different about viral content. Two decades ago, when someone read a story in the New York Times, all that mattered was the reputation of the media outlet. Now, according to Wagner, whether we trust a piece of news or information often depends on who shared it with us. If you trust the person doing the sharing, he found, you’re more likely to trust the information itself.

The editorial board of the Times may have slammed Trump’s economic plan; but when your brother-in-law shares a blog post on Facebook that supports the candidate’s pledge to “make America great again,” the guy you have an intimate relationship with will usually beat out the Old Grey Lady.

A social media ecosystem that allows for the substitution of institutional trust for personal trust is perfectly suited for Trump, who uses his own Twitter account has his primary platform for information dissemination. When Trump sends out a tweet and then someone you follow retweets it approvingly, it doesn’t matter if the Pulitzer-prize winners at Politifact have rated 70 percent of Trump’s statements either “mostly false,” “false,” or “pants on fire,” and a mere 2 percent as true.

Your brother-in-law thought it was retweet-worthy, which matters far more.

“Influence has completely decentralized,” Wagner said, adding that this state of affairs is something Trump understands instinctually, even if the billionaire may have only stumbled into it inadvertently rather than making this his campaign strategy from the outset.

For anyone looking to answer why Jeb Bush—the early “inevitable” GOP nominee, whose super PAC raised over $100 million from deep-pocketed donors—saw his efforts flounder before Trump’s viral rise, the answers are in that video.

Photo via Gage Skidmore/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman