The FCC wants to redefine broadband in a way that would pressure cable companies to improve the availability of the speeds on which Americans will increasingly rely. The nation’s cable companies, meanwhile, strenuously oppose what they see as an unnecessary regulation that prods them to do something they claim they are already doing.

On Thursday, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA) registered its opposition to the FCC’s plan to redefine broadband as 25 megabits per second (Mbps) in download speeds and 3Mbps in upload speeds.

The filing objected on the grounds that the definition would run afoul of “divergent legal standards and regulatory objectives,” including a separate FCC requirement that providers offer 10Mbps down and 1Mbps up in order to be eligible for government subsidies from the Connect America Fund.

“There is an obvious tension in defining broadband as 10 Mbps/1 Mbps when evaluating whether to provide CAF support for broadband deployment, while at the same time measuring such deployment under a 25 Mbps/3 Mbps threshold,” the filing read.

Another concern in the NCTA’s letter was how the FCC could define broadband at this new threshold but still impose hypothetical new net neutrality regulations on all broadband plans, regardless of whether they met the new definition.

In its letter objecting to the proposed change, the NCTA said that few Americans used the Internet in ways that would require such speeds.

Netflix is one of the FCC’s highest-profile supporters in this debate, but the NCTA argued that Netflix “bases its call for a 25 Mbps download threshold on what it believes consumers need for streaming 4K and ultra-HD video content—despite the fact that only a tiny fraction of consumers use their broadband connections in this manner.”

The NCTA said that “hypotheticals” advanced by Netflix and other FCC supporters “dramatically exaggerate the amount of bandwidth needed by the typical broadband user.”

“What we’re saying is that the definition of broadband should be based on how people use the service,” Brian Dietz, Vice President of Communications and Digital Strategy for the NCTA, told the Daily Dot. “Saying that someone has a 15- or 20-megabit broadband service today, and that they wouldn’t have that service tomorrow because the definition has changed, doesn’t make any sense.”

The FCC plan, Dietz said, “provides regulatory levers that aren’t needed.”

Dietz refused to directly answer whether the NCTA would support an upward redefinition of broadband as 4K streaming and other Internet-intensive activities became more popular.

The FCC’s proposed redefinition marks its latest attempt to prod Internet service providers (ISPs) to expand their high-speed offerings with a view toward the future. The agency is charged under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 with assessing the deployment of “advanced telecommunications capability” across the country and “tak[ing] immediate action to accelerate deployment of such capability by removing barriers to infrastructure investment and by promoting competition in the telecommunications market.”

Asked if the NCTA opposed the agency’s Section 706 mandate, Dietz said, “I don’t think we’re commenting on that in this proceeding.”

A key part of the NCTA’s argument in its filing was that consumers didn’t want 25/3 Internet service. The group pointed out that FCC data showed that “a relatively small percentage of consumers who have access to speeds of 25 Mbps/3 Mbps actually choose to purchase service at those speeds.” In a footnote, the group quoted from an FCC report, which said, “The adoption rate for at least 25/3 Mbps is 30 percent in urban areas, 28 percent in rural areas, with an overall adoption rate of 29 percent.”

Yet these findings only underscore a broad problem facing American consumers who shop for Internet access at the higher speed tiers: Access to such tiers is neither universal nor widely competitive. Indeed, it’s possible that the lack of competitive access to speeds like 25/3 explains the findings to which the NCTA clung in its letter.

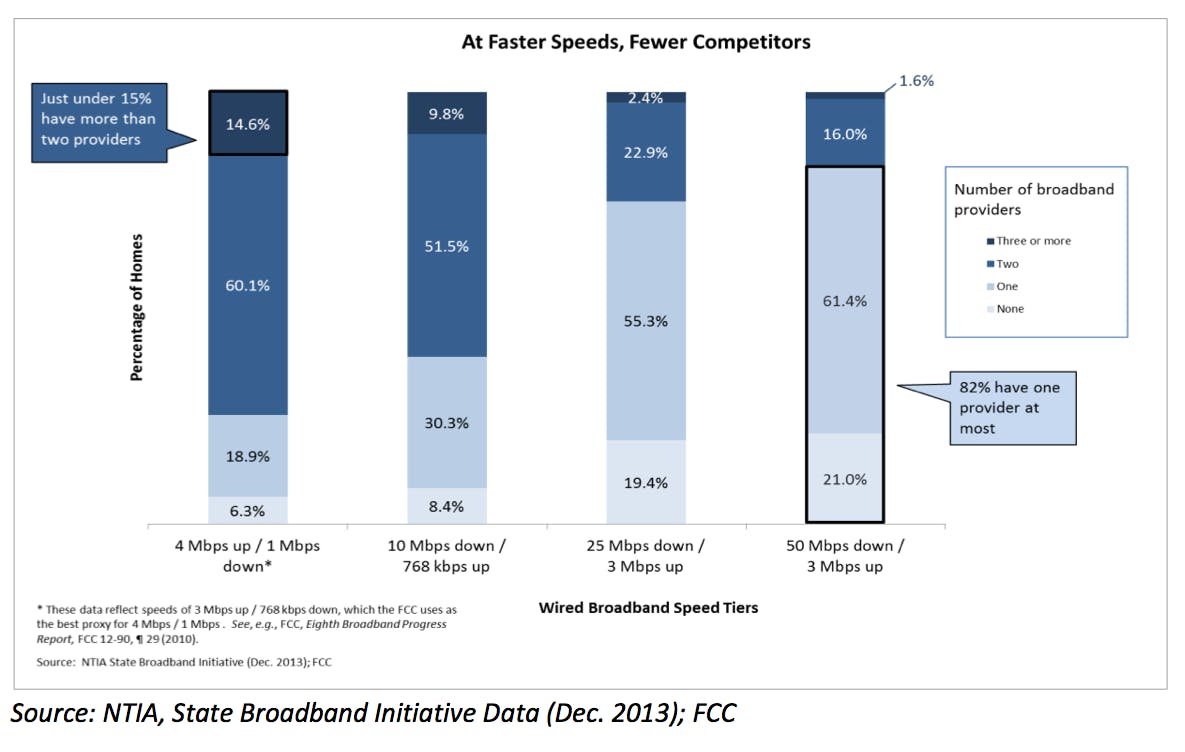

A December 2013 report from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, in which the agency studied the spread of American broadband, highlighted the lack of competition in the two fastest commonly offered tiers. Only around 25 percent of Americans live in areas where at least two ISPs are offering plans with 25 Mbps down and 3 Mbps up. Meanwhile, 55 percent of Americans can buy such a plan, but only from one company—meaning that said company has a local monopoly on that offering—and 20 percent of Americans have no access at all to that speed tier.

If the FCC redefined broadband to be at least 25 Mbps down and 3 Mbps up, it would mean that around 75 percent of Americans faced either an absence of, or monopoly on, service meeting the definition.

The Daily Dot asked Dietz whether the NCTA disputed the NTIA’s findings on the availability and competitiveness of top-tier plans, and whether, if the findings were true, they explained the low adoption of such tiers that the NCTA cited. In a subsequent email, Dietz said his group had not “spent enough time looking at the NTIA data to comment on it,” but he added that the new definition would nonetheless exceed the FCC’s mandate under Section 706.

Internet “deployment is certainly ‘reasonable and timely’ for purposes of 706,” Dietz said. “There are tens of millions of wireline customers and over a hundred million wireless customers that buy broadband service below the 25/3 standard, and they are able to use those services to communicate with friends and family, surf the Web, and watch billions of hours of video.”

Update 6:00pm CT, Jan. 26: This story has been edited to clarify the methods of communication with Mr. Dietz.

H/T Ars Technica | Photo via ryoichitanaka/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)