FBI Director James Comey has defended his agency’s demand that Apple help it unlock a terrorist’s iPhone by saying that the case “isn’t about trying to set a precedent or send any kind of message.” But across the United States, as Apple fights other demands to help cops extract data from its devices, many prosecutors seem eager to use the high-profile case’s outcome as precedent.

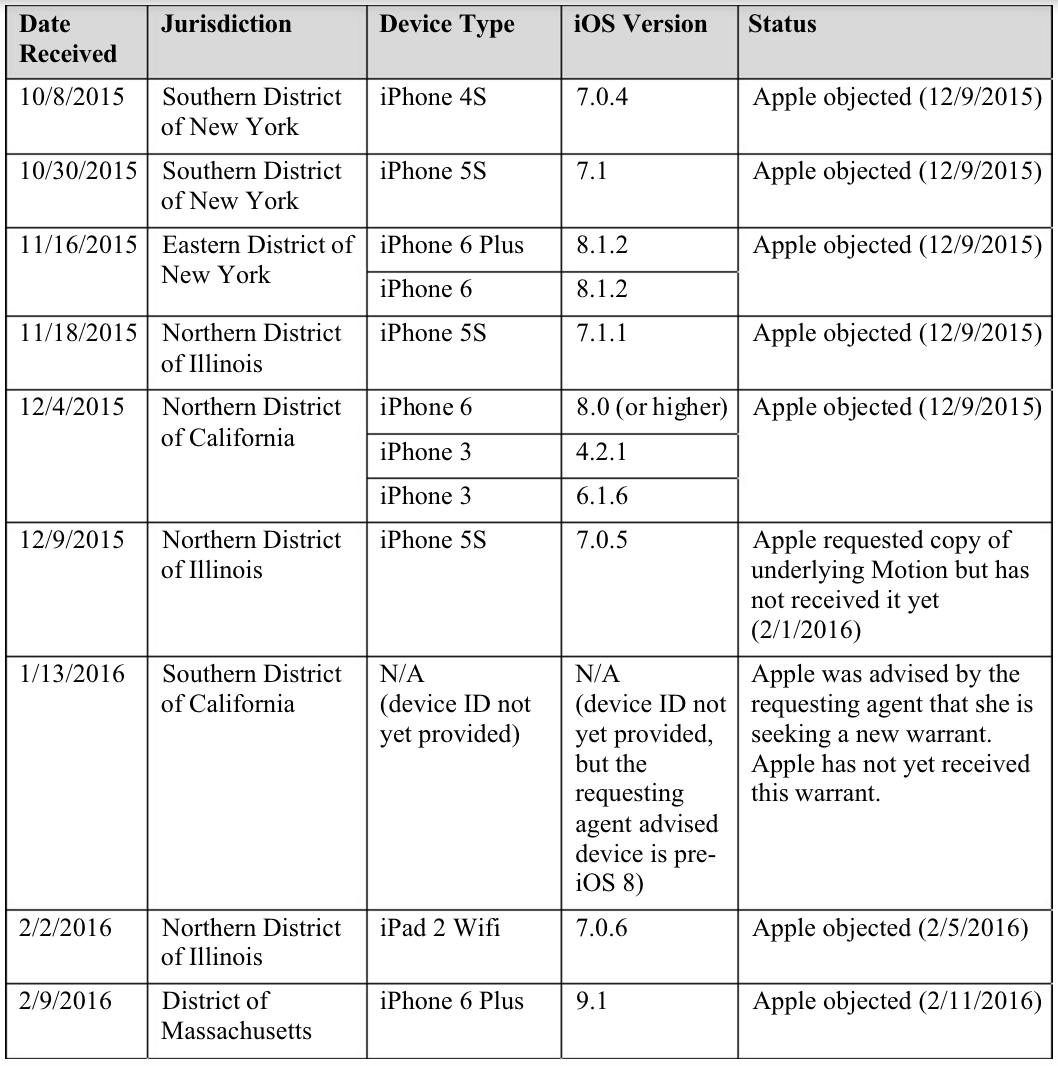

A document filed Feb. 17 by Apple’s lawyer in a separate case shows that federal courts have ordered Apple to help authorities access 12 phones in nine situations. Apple objected to seven of those requests and is waiting for documentation in the other two.

The first of these requests arrived on Oct. 8, but Apple’s nationwide effort to fight such orders only became a high-profile issue last week, when a California judge ordered Apple to help the FBI access the iPhone of one of the San Bernardino shooters. Apple said it would appeal that order, touching off a nearly week-long battle between America’s most valuable company and one of its most powerful federal agencies.

Apple CEO Tim Cook has warned that, by complying with the order to write software that would let the FBI flood the phone with password guesses, his company would be setting a dangerous precedent that could undermine its customers’ security and privacy in the future.

Apple also argued that complying with the order would place an unreasonable burden on its business. It said that it sells privacy as much as gadgetry and would suffer if it came to be seen as an arm of the government.

The fight over Apple’s obligation to assist law enforcement in accessing its devices is part of a broader debate about encryption and Silicon Valley’s responsibility to help the government.

Many senior law enforcement and intelligence officials want tech companies to design their encryption so that it can be bypassed if the government obtains a warrant to access an encrypted device. But tech companies, security experts, and civil liberties advocates warn that weakening encryption in this way would give hackers and foreign governments new ways to breach Americans’ security.

Comey has criticized Apple for adding full-disk encryption to iOS 8, released in September 2014, because it meant that Apple’s own engineers could no longer access customers’ devices. Google also made full-disk encryption an option in Android. Police and spies see the shift to stronger encryption as a danger because it gives terrorists to new ways to hide their planning.

The Feb. 17 filing, which disclosed the 12 targeted phones, concerns a phone-unlocking case in New York, the first such fight to gain moderate attention earlier this year. In that case, Apple is refusing to help the government access a drug suspect’s phone.

Federal judges issued all of these orders under an 18th-century law known as the All Writs Act, which empowers courts to “issue all writs”—an old term for “orders”—necessary to enforce their rulings. The government has obtained warrants targeting each of the phones and says that, without Apple’s unique ability to bypass its products’ security, it cannot execute those warrants.

Illustration via Max Fleishman