Warning: This post includes spoilers for Yuri on Ice up to episode 10.

Yuri on Ice begins with its hero having an emotional breakdown in a bathroom, crying after placing last at the Grand Prix finals. His dog died, he started stress-eating before the competition, and he has an ongoing problem with anxiety.

While the show doesn't explicitly label Yuri's mental health issues, they're an integral part of his characterization. Performance anxiety can be a career-altering obstacle for any professional athlete, and since the show is mostly told from Yuri's point of view, his emotional state alters our view of the story.

Yuri is a textbook example of an unreliable narrator, especially when identifying his own role in the story. For instance, he describes himself as one of the "dime-a-dozen" skaters competing in the Grand Prix, implying that he's kind of a nobody. He never acknowledges his true level of achievement, which places him as one of the top six male skaters in the world, and the highest-ranked in Japan. It's entirely possible that he'd place even higher if he hadn't been binge-eating and mourning the death of his childhood pet.

This attitude explains why Yuri on Ice doesn't have a villain: Yuri's main antagonist is himself.

Yuri's characterization is a great illustration of why "low self-esteem" is a more complex term than you might think. He isn't exactly self-loathing, but his image of himself is very different from what other people see.

When Yuri returns home from his big loss at the Grand Prix, his hometown is plastered with posters of his face, yet the show makes us feel like he's an underdog character—perhaps even a loser. He's stressed, uncertain, and sleeping in his childhood bedroom full of posters of his idol Victor Nikiforov, a seemingly flawless celebrity. Yet in later episodes, we meet a young skater who idolizes Yuri just as fiercely.

Yuri seems to think he's socially isolated from the skating community, but this clashes with what we actually see onscreen. Other skaters always seem friendly toward him, and in episode 10 we discover that he was actually the life of the party at last year's Grand Prix. He just got drunk and forgot about it, the ultimate evidence of Yuri's status as an unreliable narrator.

Yuri on Ice/Crunchyroll

Yuri's combination of anxiety and inaccurate self-image feel authentic to the life of a world-class athlete, especially when you combine them with his obsessive perfectionism. When Yuri beats himself up for "losing" a competition, he's actually beating himself up for not winning gold. That's why the central romance of Yuri on Ice is so effective: Until five-time world champion Victor Nikiforov came along, no one in Yuri's life really understood his drive to win.

Supported by his parents (who are well-meaning but clueless) and friends (who have their own lives and priorities), Yuri was never pushed to admit out loud that he wants to win gold. This is where Victor comes in, and there's a strong implication that his influence has more to do with Yuri's attitude and emotional wellbeing, not the technical skills that Yuri already practiced with his previous coach. His learning process isn't so much about improving as an athlete—it's about Yuri getting in touch with his emotions, and gaining more confidence so he's in peak mental condition to match his physical expertise.

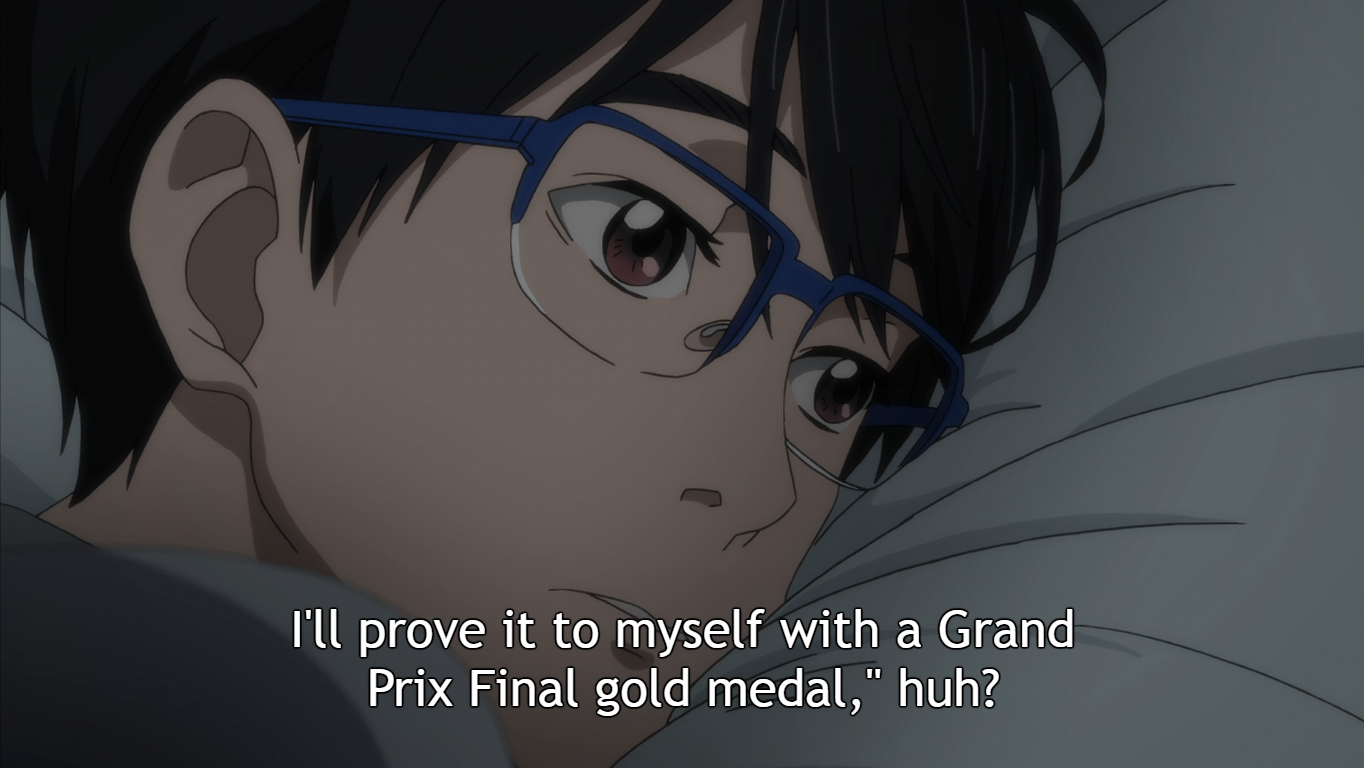

Now we're nearing the end of the series, Yuri has won several competitions, and is in a relationship. He's certainly feeling better than he did in episode 1, but there's no suggestion that his anxiety is "cured," or will magically vanish now that he's found love and professional success. Even in episode 10, when the top skaters are relaxing in Barcelona before the Grand Prix finals, we still see Yuri lying in bed and panicking about the competition.

Yuri on Ice

If we had to pin down Yuri on Ice by genre, we'd describe it as a sports anime/romantic comedy. However you choose to describe it, it's an undeniably lighthearted, funny, and uplifting show—which is why Yuri's complex characterization is such a welcome highlight. It proves that TV doesn't have to be grim and hard-hitting to deal with mental health issues in a thoughtful and nuanced way.