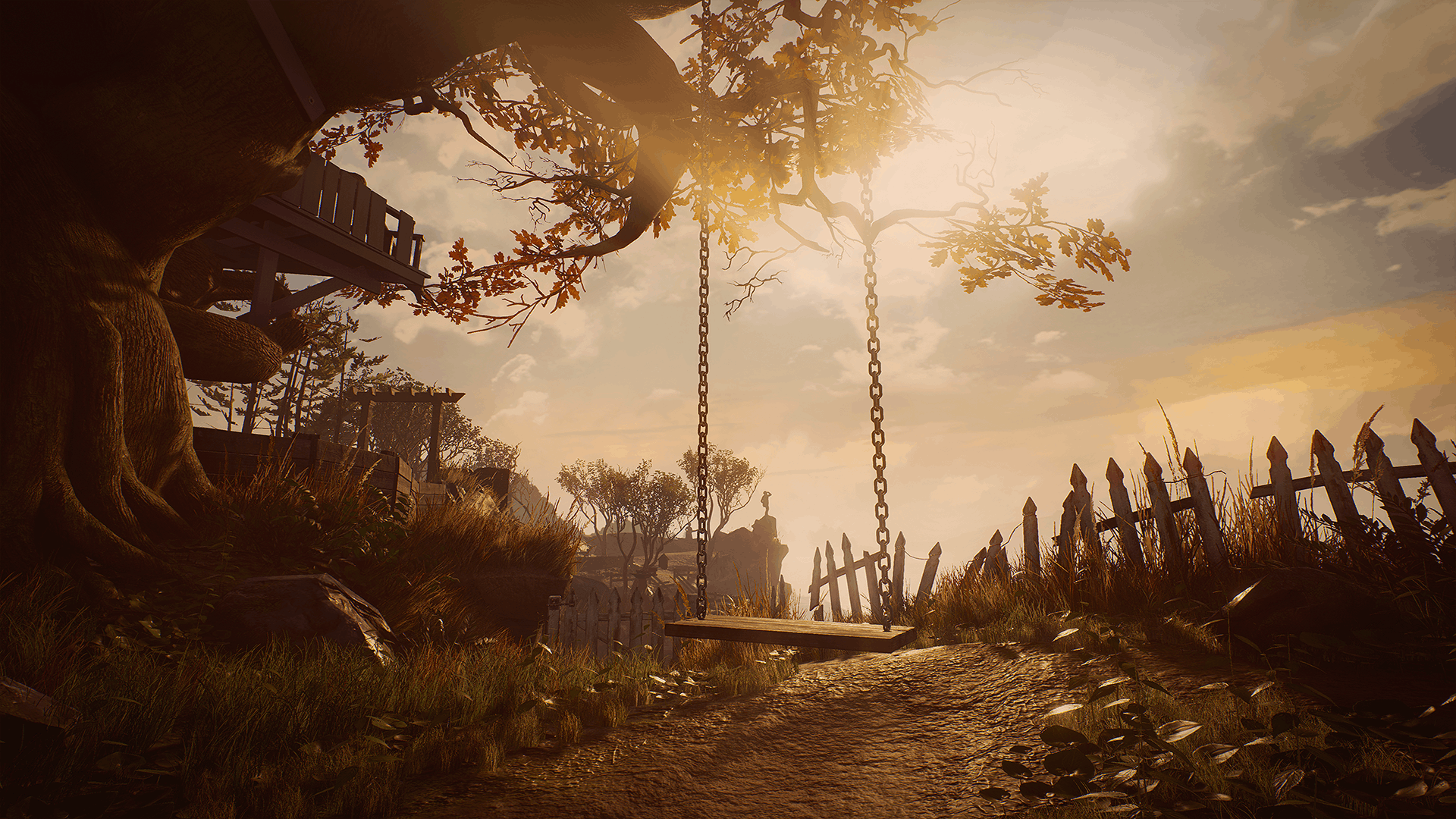

My recent demo of What Remains of Edith Finch opened as the titular character returns to her childhood home. Towering and ominous, the house represents the mysterious lineage of her now-deceased family members. As she enters the house, Edith explores the bedrooms of the other Finches and recalls the final moments of their lives.

I played through a section of the game called “Molly’s Story,” where a young girl is locked in her room, starving. Molly searches through the room for something to eat and eventually transforms into a cat, hopping out the window to chase a bird. From there, the game became a fantastical sequence where I controlled an owl, a shark, and a twisted sea monster in rapid succession.

As a narrative-driven indie game, What Remains of Edith Finch uses unique presentation to explore the perspective of multiple family members. I spoke to developer Giant Sparrow’s creative director Ian Dallas about designing the game and the many inspirations for its ominous tones.

Can players expect lots of surprises like the fantastical twists in Molly’s story?

There are others that are at that level or close to it, but that’s probably the most ridiculous in some ways. It’s meant to evoke a little girl’s dream, so we wanted that one to feel the most dreamlike. And it’s probably got the most varied control schemes of the stories, it has an absurd number of different, little prototypes. It was the very first story we ever did, and set a high watermark, the other stories got a bit simpler as we went along.

The other stories tend to be played from one or two perspectives, instead of like six different control schemes in totally different environments. But we actually felt like (Molly’s story) was a good introduction to the game because it does a lot what the rest of the game does, but in a more concentrated form.

The entire segment had a very unnerving, creepy tone. Would you describe this as a horror game?

I would say it was not primarily designed to scare people. In that sense I wouldn’t quite call it a horror game, but it looks like a horror game. It’s a game about the sublime manner of nature, that was the original inspiration for it, so each of the stories is really about what it means to be overwhelmed. Someone in each of the stories is coming across something that overwhelms them physically and emotionally. Its not presented as a horrific experience, but it hopefully raises some troubling questions for players about the game and about their own lives.

Internally, we talk a lot about trying to make it feel ominous, but not really ominous or gory—something that really bugs me is when people call it “spooky.” When I hear that, I think of “Monster Mash.” Its a different thing, but people really like things in that wheelhouse. I think people like Lemony Snicket and even Edward Gorey are veering off into that more comedic tone. Ideally, we’re trying to evoke some fairly serious concerns and the “spoooooky” vibe fights that a bit, but people will take away whatever they want from the game.

Were there any specific inspirations for the tone of the game?

In terms of the psychological horror aspect, its a game about what it feels like to realize you’re in a universe that is more or less ambivalent to you. And getting back to that element of the sublime horror of nature, the clearest references I found were in weird fiction, a genre that sort of predates horror in the 1930s, people like H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur Machen, Edgar Allen Poe, and a little later, people like Neil Gaiman. Not horror, but with something weird going on, and often short stories, which is one of the reasons we weeded up doing this game as a series of short stories, because it just so naturally fits in with those kind of tales about a bizarre universe and someone’s place in it.

With regards to stories about families, our canonical reference was One Hundred Years of Solitude, the magical realist book by Gabriel García Márquez, which does a really great job describing four or five generations of a family. There were a lot of great things we learned from that, like having one character that persists throughout the story is really helpful to give a point of reference for things.

The house was a way for us to ground the experience for players. A lot of the game was about these ethereal ideas of family and relationships, death and the passage of time, and the house was a way for us to make that into something that the player could interact with and return to. It was a way of giving the player some kind of tactile relationship with the way the family evolves over time.

Even the structure of the house, what you see when you walk up to it tells some of the story. You can see how the family started out from this sensible normal place on the first two floors, but as people die they shut off the bedrooms and never open them again, so they need to keep adding on to the house in later generations, and they build off this organic growth. The stories, by nature, are fairly intense and a little strange. Each story is different from the others, and if the game was just stories, it would be a little formless. It would be very easy to forget about the fourth story you played when you’re on the tenth story. But the house is a way to provide a spine for the stories, when you’re going from the bedrooms into the stories, and back to the bedrooms, it grounds the surreal experience in something more mundane.

Was it difficult to tell one overarching narrative split up among so many short stories?

It’s meant to feel like you’re bumping into these things, and I think there are only two or three stories you have to finish in order to move forward, but in a typical play through most players will find the stories in the same orders. And that’s because the house is this labyrinthine thing, we wanted it to feel overwhelming and hard to navigate, but secretly it’s relatively easy for players to find their way through the house, because we decided it was much more interesting to move on to the next story than have to backtrack and get lost. It was meant to feel more open than it actually is.

It’s a very difficult process to blend them all together, but thankfully the individual stories end up being a lot easier to tell. They exist in their own little universes, they can have beginnings middles and ends, they may last three minutes or 20 minutes, depending on that story. That part was relatively straightforward and really fun, but the Edith side of that, the through line of the way all these stories tie together was this excruciating odyssey, that really only ended a few days ago, after years of trying to massage these things into place.

This whole game could be seen as the story of one family. After each story is finished, you bring up the family tree and fill in the portrait of that family member. Playing through Molly’s story you get a sense of who she is as a character, but being Edith and looking around her room gives you another. Neither of those are complete in terms of pacing, tone, and emotional intensity, but the bedrooms and overall house experience is a more subdued, familiar experience. You’re walking around in first-person learning about these family members, but you’re not transforming into different animals as Edith, and that was partly just to give players a chance to catch their breath, so we could hopefully take it away again in a few minutes.

Edith’s story, the general arc of her concerns having grown up in this house, really ties back into what these stories are about. The immediate incident is that her mother has died recently, leaving Edith as the last Finch family member that is alive. She’s come back to this house to figure out what happened to people, partly because she’s concerned about what might happen to herself. But also, when she was a child growing up in this house, she wasn’t allowed inside any of these bedrooms, and she now is an adult coming back with a curiosity about those stories. That was the jumping off point, but once we did a couple of them, some elements began to emerge, like the perils of imagination, or the way things evolve over time, and the issue of time in a family. The overarching story was rewritten to speak more to those themes.

Did you approach each story from a different design perspective, gameplay-wise?

Every story has completely different mechanics, the goal is to get what the player is doing to evoke who that family member is and what their concerns are, and because every family member is different, every story ended up being quite distinct. Most of the stories are played from a first-person perspective, so they have that in common, but they all are their own individual snowflakes. Part of that is wanting to keep players in a beginners’ mind, where they don’t get too used to the controls and do the traditional thing where once they figure out what to do, they do it as fast as they can to get to the next stage. We’re always trying to keep people like they’re playing a tutorial, but in a fun way, where they’re always discovering things about the family, as well as what they can do.

What Remains of Edith Finch is coming to PS4 and PC on April 25.