Warning: This review contains spoilers for the first and second seasons of The Walking Dead game.

When a video game bashes you over the head with a story about the futility of hope in a post-apocalyptic nightmare, playing the game itself can eventually start to feel pointless.

The first season of the episodic, interactive storytelling game The Walking Dead from Telltale Games put the studio on the map in terms of the huge profile it currently enjoys. It was also a relentless piling-on of awful tragedy after awful tragedy.

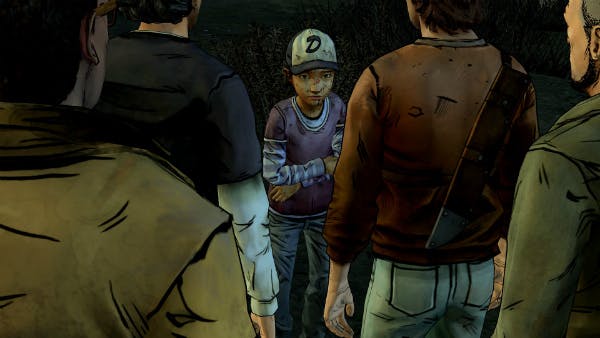

There was, however, a ray of hope at the end of the first season. The main character, a 10-year-old girl named Clementine, was alone. All the adults she had been traveling with were dead or missing. But Clementine proved she had what it took to survive the unforgiving world of a zombie apocalypse.

As the protagonist in The Walking Dead: Season Two (i.e. as the character whose actions the player controls), Clementine spends the entire game putting those lessons to the test. The end of the story this time, however, offers very little hope, and that is the weakness of The Walking Dead: Season Two.

The rich, dark string chords of the opening credits to The Walking Dead: Season Two quickly evoke the misery that was season one. Story choices carry over from season to season in Telltale games, so just how awful a state Clementine begins season two in depends largely on a major choice at the end of the first season.

For me, Clementine ended the first season by shooting and killing the man who had virtually adopted her and kept her safe. With that in mind it felt appropriate that within the first five minutes of the second season two people were dead, and within 15 minutes Clementine was already alone and in dire straits.

The Walking Dead games tease you with hope every 30 minutes or so before they yank it away from you. Just in case you forgot: The zombie apocalypse sucks. Every time Clementine finds a group of survivors, you’d be foolish to put any hope in the group maintaining its numbers or integrity for very long. For anyone who’s played the first season—or watched any modern zombie movie or television show for that matter—that’s no spoiler.

In fact, at many points during my playthrough of The Walking Dead: Season Two, I had the distinct feeling that the writers were thumbing their way through an old playbook. The Walking Dead games from Telltale don’t assume the player has read the Walking Dead comic or watched the television series. If you do engage with both, however, you see the same narrative points and themes repeated throughout every version of Robert Kirkman’s Walking Dead universe.

You will see turncoats, tyrants, undependable cowards, lunatics, misplaced heroism, and terrible tragedy. This is a world where, if a group of well-supplied adults finds a little girl with a deep gash on her arm, they are more inclined to lock her away for an evening to test whether the wound is a zombie bite or not, rather than help her. If she turns, it was a zombie bite.

The Walking Dead games rely on a sense of relentless dread. Crossing a bridge in the open, walking across a frozen river, even finding other survivors are all recipes for disaster, and it’s draining to experience. A pregnant woman, usually a sight that denotes happiness and hope, evokes thoughts of the noise a baby is going to make and the drain on supplies.

Every episode of The Walking Dead: Season Two ends in horror, whether it be the separation of friends after a zombie attack, powerlessness at the hands of ruthless survivors, or gun battles that fade to black before the credits. Even with the need for episodic games to end each episode with a cliffhanger, taken back-to-back the endings of each episode become predictable. The specifics don’t matter. The emotional impact does.

Season Two, whether intentional or not, is a statement about how diversity in video games can and does work. Clementine becomes the figurative glue that holds groups together in times of extreme duress. She takes the big risks that keep everyone alive. She becomes a voice whose guidance holds as much or more weight than the adults’, because Clementine has survived outside in the zombie apocalypse longer than most of the people she meets.

Clementine is a statement that the hero of a video game narrative doesn’t always have to be cast in the typical mold of the hero, like the seasoned war veteran (though Clementine is certainly seasoned by trauma), or the muscle-bound warrior (Clementine proves that spirit, more than anything else, defines a warrior), or the born hero whose leadership role is never in doubt (Clementine constantly earns the respect and authority she wields).

In fact, for not making heroism look so easy, Clementine actually becomes more of a hero than the protagonists of most video games I play. That’s not to say that Clementine is a bastion of clear-cut good, however. No one can survive the world of The Walking Dead without a whole lot of moral flexibility.

Had I played the episodes one-by-one as they were released I might not have played Clementine quite as hard-nosed, to the point of occasional viciousness, as I did. But after a 10-hour run, it’s easy to cast Clementine as an antihero who enjoys seeing justice done to the wicked, no matter how bloody the retribution.

I think there’s a brutal honesty in that potential effect of playing the episodes in rapid succession. There’s something compelling, to me, about a player of The Walking Dead: Season Two changing their moral compass as a result of steeping themselves in such an amoral world. It’s even more compelling to me if a player can use an 11-year-old girl as the instrument of their amorality.

Even accepting the overwhelming awfulness of the world of The Walking Dead: Season Two, the endings of the game—all of them—were terrible.

You can’t step into any version of The Walking Dead, comic book, television show, or video game, if you can’t get over a lot of characters dying. You get one or a small handful of protagonists who repeatedly survive, without which the story would lack a force to drive the narrative. And even then, when you think you’ve identified a member of that limited set, the story might yank him or her away from you.

That said, the point of surviving is to have a chance to make a better life. Without that hope, you may as well just take the easy way out, rather than try to slog through a zombie infested world. Throughout zombie fiction, characters run into the corpses of people who made just that decision.

I was downright angry with the ending of The Walking Dead: Season Two that I arrived at naturally. Maybe I was just punchy after 10 hours of watching people die, some in horrible ways, and feeling like there was nothing I could do to improve Clementine’s situation.

One can rewind The Walking Dead and replay chapters of specific episodes. The ending I stuck with would be the starting point for the eventual third season, so I looked up all the various endings online, to try and find one more palatable than the one I got.

But it turns out every ending of The Walking Dead: Season Two is tonally awful, either so vague as to be unsatisfactory or just piling on the soul-crushing horror of Clementine’s existence.

That hopelessness made the entire exercise of Season Two feel pointless. I don’t find it daring, nor clever, nor edgy, when fiction decides to end on a nihilistic tone. I sometimes find it manipulatively cynical, and I think the audience needed and deserved a respite, even a temporary one, from the horror that defines Clementine’s world.

Up to its very last seconds, The Walking Dead: Season Two can offer profound hope, and then snatch it immediately away, leaving nothing but a pit of misery to sink into. One could argue that’s the point of The Walking Dead. One could also point at the current, hopeful state of the comic book as a counterpoint.

It took the comic a long while to get there, though, and the television series is riding into its fifth season on a wave of concentrated awful, so it may take the video games from Telltale just as long to finally begin turning around.

Unlike the comic book and television series, however, The Walking Dead video games are participatory narratives that are experienced, not observed. And for me the awfulness is starting to become overwhelming. I’m not suggesting that The Walking Dead series by Telltale needs to switch to sunshine and roses, but I do think there needs to be more variety in tone.

Pessimism already feels like a narrative crutch for The Walking Dead games. The endings for Season Two collectively did the worst thing an ending can do for a video game franchise: They made me unsure that I cared about season three.

Score: 3.5/5

Disclosure: Our review copy of The Walking Dead: Season Two on Steam was provided courtesy of Telltale Games.

Screengrabs by Dennis Scimeca