Terry Gilliam wants to know why the horde of eager press gathered to chat with him early on Saturday at Dragon Con doesn’t have better things to do.

“Why aren’t you all at the parade?” he jokes as he greets us.

You’d be hard-pressed to find an entertainment reporter who wouldn’t choose to spend the day instead with Gilliam, who is perhaps best known as the original animator and only American-born member of Monty Python. Although he snagged directing credits on Monty Python and the Holy Grail and The Meaning of Life, it was his dystopic fantasy masterpiece Brazil in 1985 that garnered him praise as one of the most visionary directors in Hollywood.

It’s a calling card we suspect Gilliam would return if he could; since his run of critically acclaimed films—including Robin Williams’ compelling performance in The Fisher King—his career has plotted a steady trajectory away from big-budget releases toward smaller independent projects that let him unleash his creative vision unrestrained. Gilliam has openly decried the increasing unwillingness of Hollywood studios to bank on anything but a major blockbuster or an independent unknown.

His latest film Zero Thoerem, a stylish sci-fi brain-bender about a man seeking to quantify the futility of life, is an independent offering that narratively echoes many of the themes Gilliam has struggled with in his own film career.

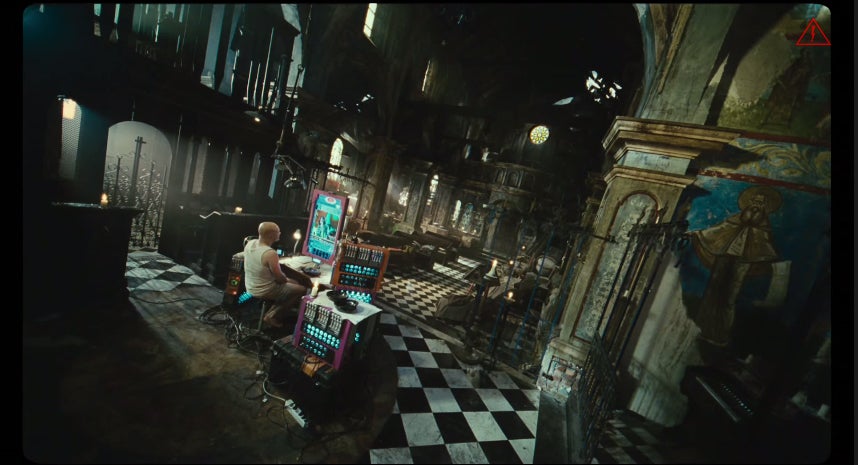

Entering widespread release on Sept. 19, Zero Theorem stars Christoph Waltz as the erratic computer programmer Qohen Leth, along with a stellar ensemble including Matt Damon, Tilda Swinton, Ben Whishaw, and Gwendoline Christie.

Gilliam says two-time Academy Award-winner Waltz was a delight to work with. “He’s never offscreen,” Gilliam says. “He is the movie.”

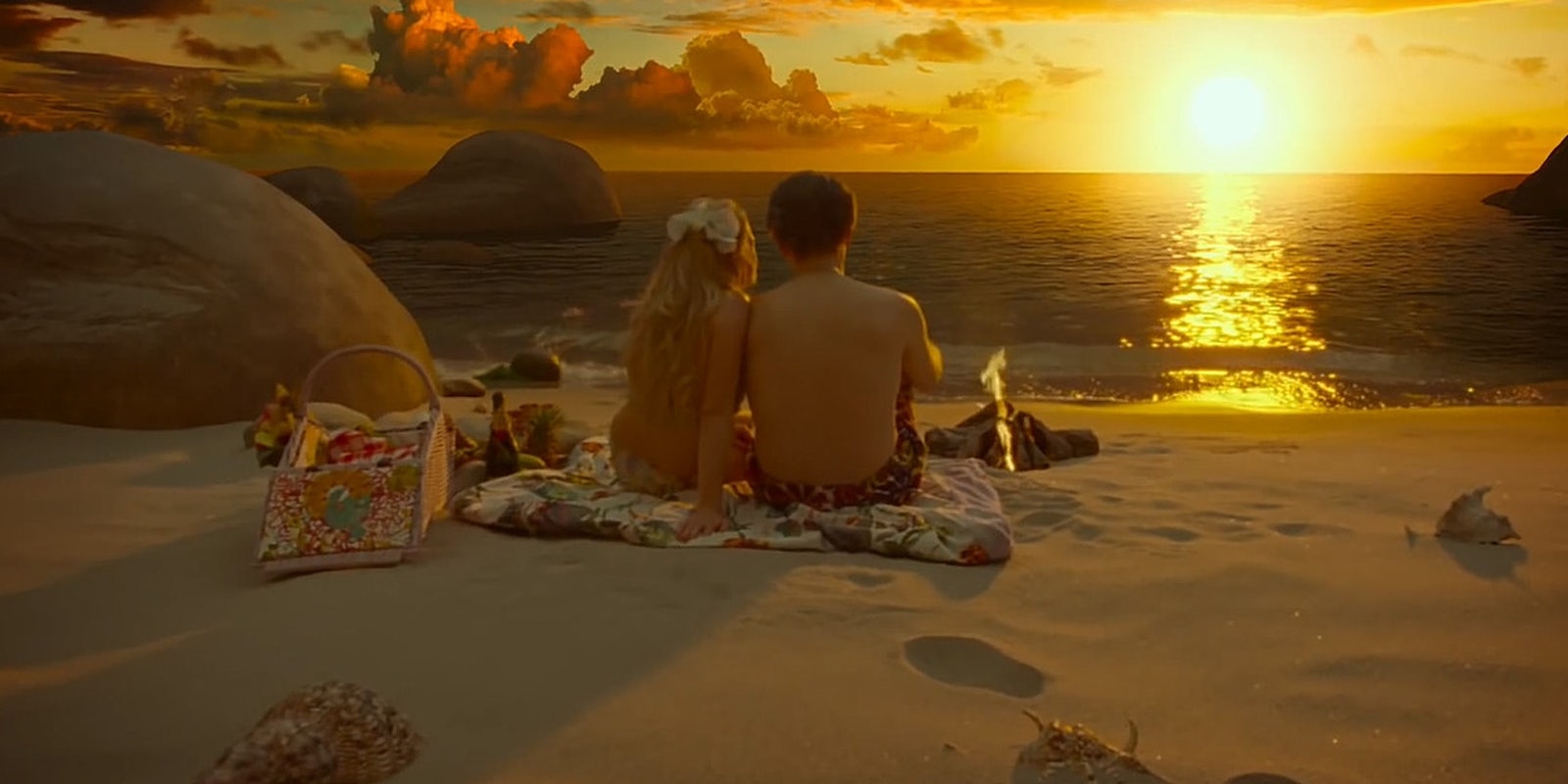

Gilliam calls Zero Thoerem a “vinyl” film because it was shot on analog with digital components, including one scene which Waltz shot on his iPhone in Germany. The film is full of an awareness of the tension between old and new technology—think the bright colors of Rio, filtered through the dystopic overtones of Blade Runner and the breezy retrofuturism of Dieselpunk.

To Gilliam, Zero Theorem is a “film about impotence” at its heart. As Waltz’s Leth attempts to solve the meaningless nature of life, we see parallels to the many various obstacles to Gilliam’s own creative vision. Perhaps the most notorious of these are the many delays to his attempts to adapt Don Quixote. As chronicled in the acclaimed documentary Lost in La Mancha, the adaptation long seemed to be an impossibility. A report from last month in The Wrap, however, claimed that he had achieved financing and that filming would finally begin in December.

Gilliam was mum on the subject. “I’ve gotten to the point now, any time I say anything about it, I doom it,” he joked.

He knows—or is willing to say—even less about the upcoming 12 Monkeys television series, planned to air on SyFy in 2015. Though Gilliam directed the acclaimed 1995 film, he says he was never consulted about plans for the TV adaptation. (You can view the trailer here.)

He did, however, call the rumored casting of Emily Hampshire a “major breakthrough” that would make the series work. Hampshire is reportedly playing the iconic role originally played by Brad Pitt, now Jennifer Goines.

12 Monkeys is a prime example of the kind of earlier filmmaking Gilliam returns to in Zero Theorem. Several critics have seen Gilliam’s recurring theme of social dysfunction working on a tortured soul as a kind of tryptych, which includes Brazil and 12 Monkeys and concludes with Zero Theorem. Gilliam handwaves the idea, and says that Brazil was about then, and Zero Theorem is about now.

“I do take full responsibility for the creation of Homeland Security,” he jokes. To Gilliam, Zero Theorem is a reflection of the disconnection of the human spirit when it relies too deeply on technology, and an attempt to reconnect with the real world.

You lose your ability to really relate [to] others. How do you get it back?… Most people now, what are they? Are they just a neuron connecting other people’s tweets?… As Rene Descartes would say, ‘I tweet, therefore, I am.’

Gilliam says he has no problem with the often polarizing reactions these films evoke, and says that one of the great current sins in filmmaking is fear of giving offense.

“If we’d’ve behaved like that there never would have been Monty Python. We went out of our way to offend, to shock… not in a cheap way. It’s trying to get people to think, and some of that means shocking them, saying rude things. Am I causing harm or am I doing or saying something that someone might react to?… We’re at a stage where people are so frightened of saying things because they might say the wrong thing.”

Gilliam cites Hollywood writers as being among the chief purveyors of this form of self-censorship, and notes that the ending of Zero Theorem is not the version that was originally scripted.

“It’s a very hard balance to play this game [of compromise] and get films made,” he said. To him, most of the work is about overcoming self-censorship. He describes his filmmaking as an effort to “leave bits of shrapnel in people.”

“To me, films are about getting inside of people,” Gilliam said. “Everyone gets excited about technology. It doesn’t interest me in the least… The equipment is not what it’s about. It’s about ideas, talent, and skill.”

He cites the example of a viewer who saw The Fisher King when it premiered and then walked home 20 blocks in the wrong direction.

“That’s what so many films have done for me, and I suppose that’s what I’m trying to do. When that works you feel you’ve pulled something off that’s worth it.”

Screengrabs via YouTube