Perhaps you remember the Kickstarter video for the first person shooter Strafe in which a child’s head melts and explodes like Toht’s at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark?

Strafe was among the titles shown off at E3 by indie game mega-publisher Devolver Digital. Devolver has a reputation for having an in-your-face attitude about games, and so Strafe is a perfect game for it.

The Kickstarter video made Strafe seem like a game where you bludgeoned your way through levels, laughing at the bloody giblets raining down all around you, while simultaneously reminiscing about the days when shooters were simple affairs that didn’t involve class builds and leveling and weapon mods.

What I discovered at E3 is the sophistication lying underneath Strafe’s outrageous personification. It’s a serious first-person shooter designed to challenge veterans of the genre and to punish anyone who doesn’t take the game seriously enough to step up their performance.

Casual shooter fans might hate Strafe, but the FPS die-hards are probably going to love it.

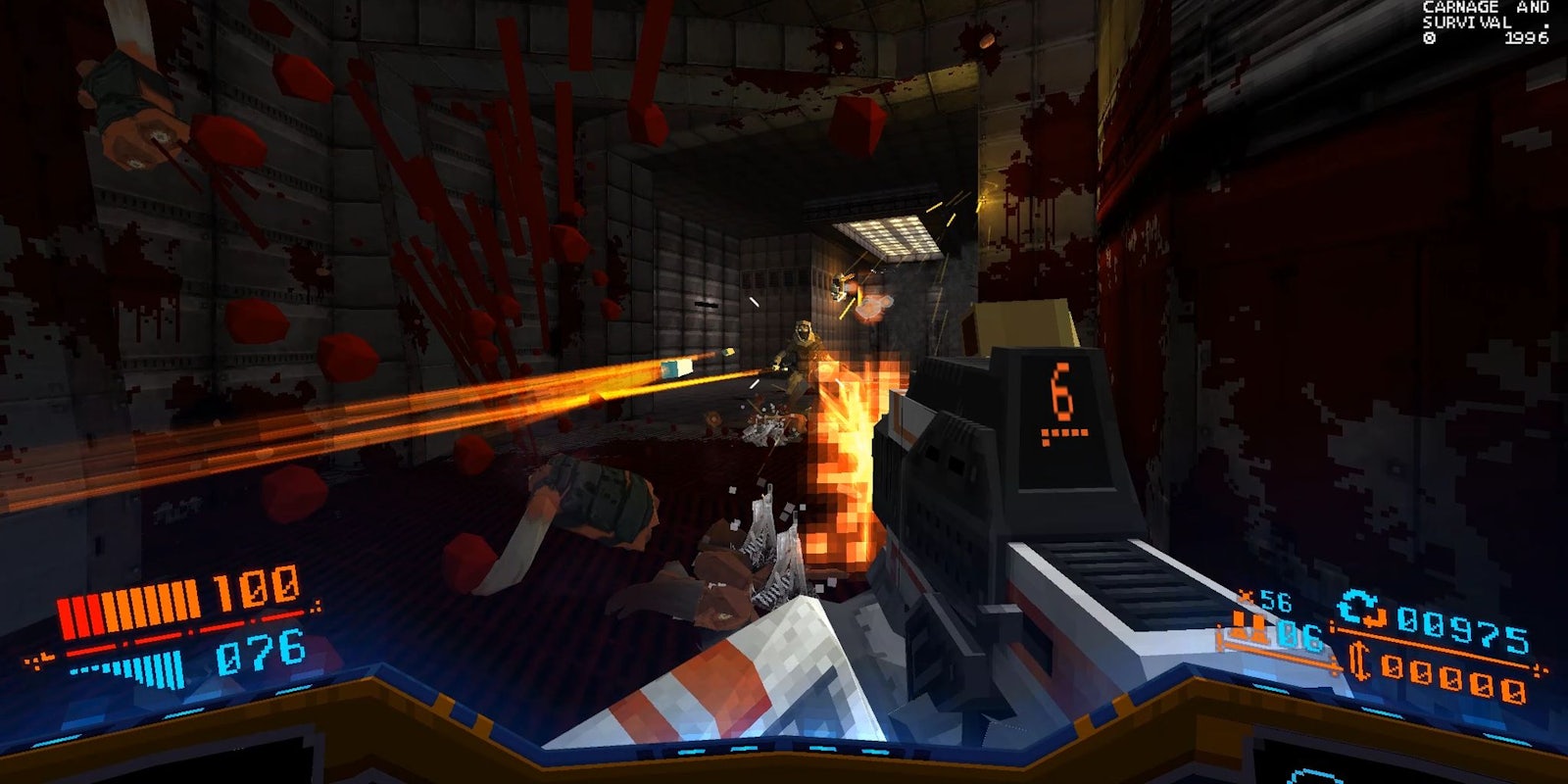

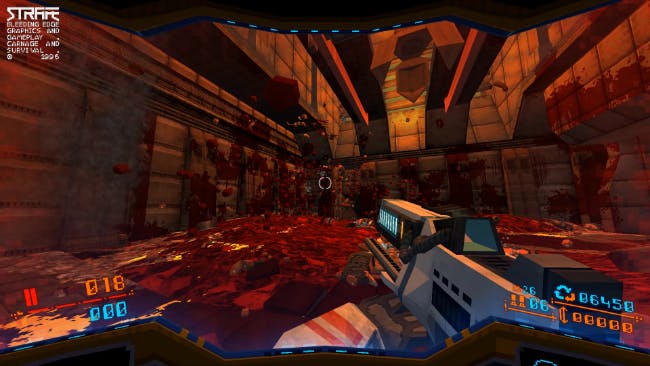

Strafe is designed in an art style that Thom Glunt, game director and co-founder of Pixel Titans, calls “retro low poly.” The aesthetic is meant to evoke memories of Quake, and Strafe did remind me of Quake during my short hands-on demo session in terms of how quickly and smoothly the game flowed.

Strafe is a roguelike, which means the game is over if you die only once. No upgrades you earn are persistent, no weapon modifications are permanent, if you want your character to become more powerful over the course of the game you have to stay alive.

The game is formally broken down into a structure that’s reminiscent of the way Super Mario Bros. is broken up into Worlds and levels. In Super Mario Bros. you beat World 1-1 through World 1-4, and then advance to World 2-1. In Strafe, the game is broken down into Levels and zones. You start at level 1, zone 1, advance to level 3, zone 3, and then move up to level 2.

There is only one element of persistence in the entire game. You begin on a spacecraft that acts as a level hub. There is a single, working teleporter in your ship that transports you to Level 1-1. There are also broken teleporters in the ship that will transport you to higher levels if you repair them.

You repair teleporters by finding components within the levels. You will only find one component within the level. In other words, somewhere between Level 1-1 and Level 1-3, a single component is waiting.

You can only keep the component if you make it all the way through the level without dying and return to your ship. You can then use the component to repair the teleporter to the next highest level, and it takes five components in total to repair a teleporter.

In other words, you need to get through Level 1 without dying five times in order to gather the components to repair the teleporter that brings you to Level 2-1. By completing Level 1 that many times you’ve proven that you’ve mastered the level, and therefore earned the right to start your next game instead at Level 2. This is how Strafe rewards performance.

Glunt calls Strafe “a playground of death.” Bodies don’t vanish from the ground. Blood shoots out from decapitated corpses and paints the floor, walls, and ceilings. The blood also never vanishes. Gibs explode everywhere. But there are design-based reasons for this. It’s not just about spectacle or being outrageous for its own sake.

Strafe’s levels are procedurally generated, which means they’re different every time. Bodies become markers by which to remember where you’ve already been, because you can’t memorize what the levels look like.

You’re also given beacons to follow, lightpoles that are green on one side, and red on the other. If you’re following green lights you’re moving toward the exit of the level.

Strafe is loaded with enemies that spray orange acid all over the ground, and the acid is also permanent. Blood covers and nullifies the acid, so the smart way to handle rooms filled with acid-laden enemies is to kill them first, and then kill everyone else so that the blood covers the acid and makes the room passable again.

There is a weapon-improvement mechanic in Strafe, but it isn’t bogged down with earning experience and assigning upgrade points. Weapon upgrade boxes are spread throughout the levels. Upgrades can increase the damage or decrease the reload time of the gun, just give two examples. And the upgrades you find in these upgrade boxes are randomized.

This is therefore another way to reward player performance. If you live long enough to collect enough weapon upgrade boxes, eventually you’ll max out all the different upgrades for your gun and will be ready to tackle the tougher challenge of the later levels.

There are some player-controlled upgrade systems. You collect scrap from fallen enemies which may then be used to craft ammunition or armor. Or you can sell the scrap for credits to purchase upgrades like speed or jump boosts.

This, again, becomes a performance reward mechanic. If you don’t waste bullets, and take fewer hits to use up less armor, the more scrap you have available to purchase those upgrades.

The sum total of these design elements make Strafe much more sophisticated than it may appear on the surface, and I think it’s going to surprise FPS fans who haven’t kept up with coverage of the game and walk into the game entirely fresh.

Strafe is scheduled for release in 2017.