BY MIGUEL CONCEPCION

Picking up a virtual sword sticking out of the ground should not be impressive in 2014. It certainly should not excite most of the attendees of this year’s Game Developers Conference, the largest yearly gathering of video-game makers in the world. Yet somehow, the combination of bending down and gripping the sword was the first of two “wow” moments when I took Sony’s Project Morpheus for a spin.

Sony’s announcement of joining the virtual reality market mirrors their formal foray into motion control back in 2010, which also happened to be at GDC. Back then, my reaction to the PlayStation Move evolved from initial skepticism into disappointment. Sony’s studio partners were diverting their game development resources to implement Move functionality, sometimes at the expense of content like additional levels and time that would’ve otherwise been spent polishing a game.

Yet there I was yesterday, wholly impressed that I was picking up a sword by simulating a grip with the Move while looking through the Morpheus headset. Could Sony have foreseen the renewed interest in VR four years ago? Possibly. The fact is, “Project Morpheus” is about making the Move relevant again as much as it is making a consumer-friendly VR headset.

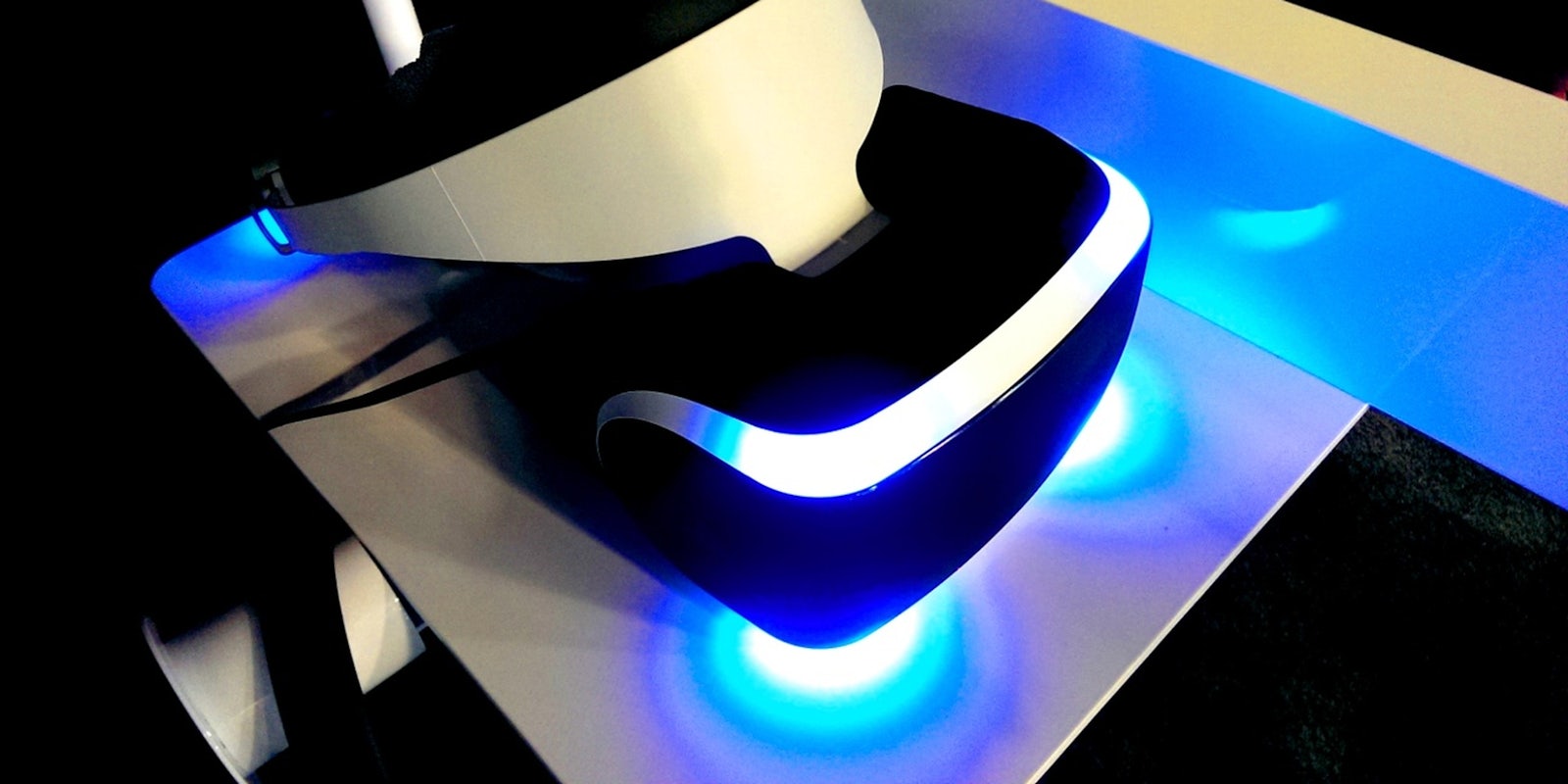

Even without a firm release date or window, Sony was still smart to give its headset a convincingly finished look, setting itself apart from the prototypical design of the Oculus Rift. The Morpheus’s Daft Punk-inspired glow will continue to turn heads at future trade shows, even if the headset is still due for several revisions. For someone who wears glasses, the unit’s tight design makes it slightly less comfortable than the Oculus. That said, Sony has the edge in air circulation, as their headset has gaps at the bottom to ensure the space around your eyes isn’t entirely under pressure.

The sword-wielding exercise was part of a medieval-themed tech demo in which I was able to punch and slice a suit of armor. I also played around with a virtual crossbow; the Morpheus spokesman advised me to take into account the target distance and the arrow’s arcing flight path. Even with a five-minute demo, there was time to experiment with interactivity that wasn’t spelled out by the spokesman. That included forcefully grabbing the suit of armor with one hand and punching it with the other. It felt rewarding to be an assertive combatant. The demo predictably ended with a dragon encounter—the intention was not to fight it, but to be reminded to look up and get the sense of scale of something so large.

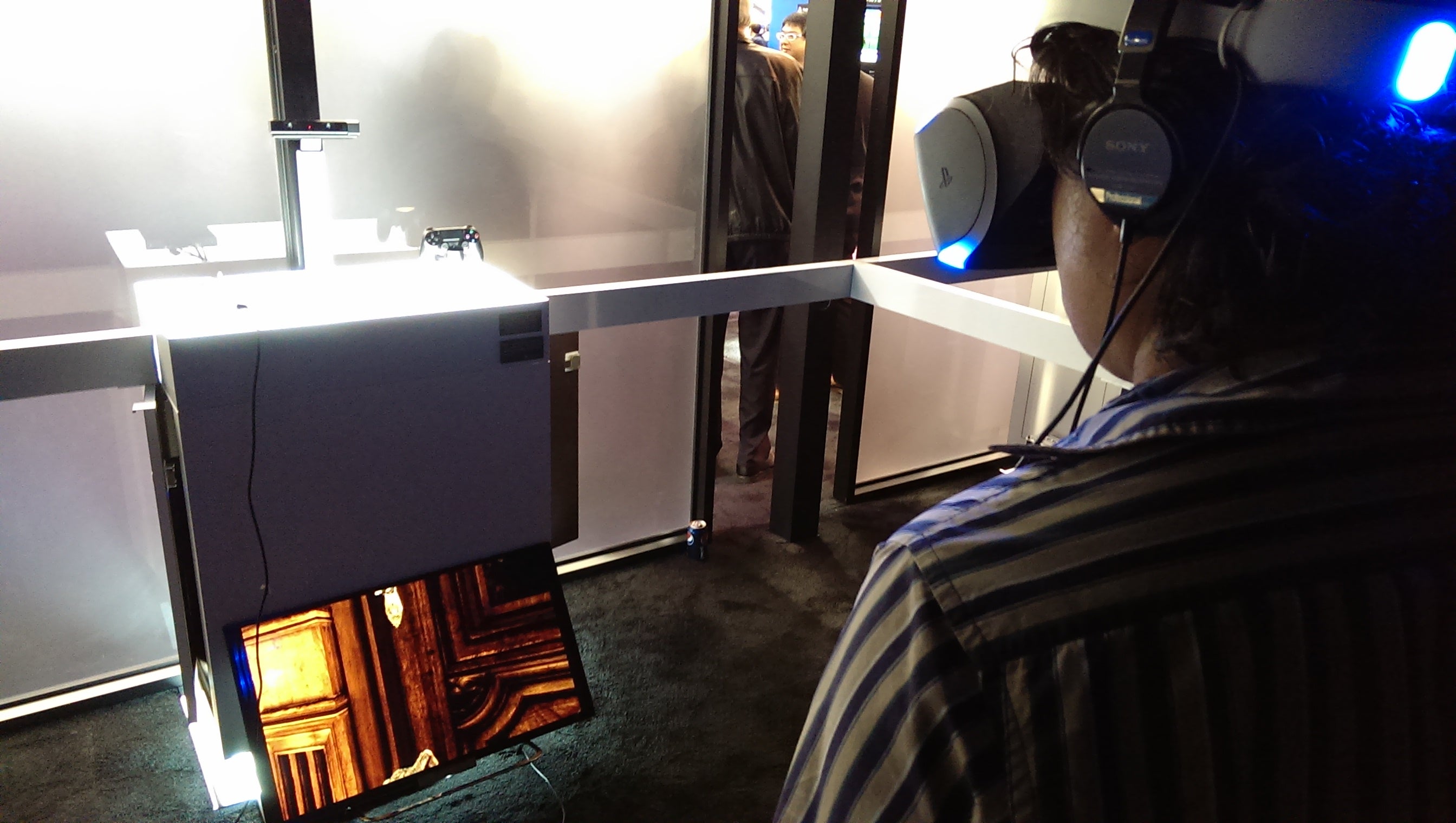

The benefits of being able to physically look around were made apparent in the two other Morpheus demos. One was a VR-customized level from Eidos Montreal’s Thief. With the help of a DualShock 4 controller to move back and forth, I used my body to control the camera as I navigated through the most familiar kind of Thief settings: a burning mansion. Although this demo had its share of glitches, seeing VR applied to a familiar console/PC game was an effective tease of the possibilities of VR in AAA games.

I finished off my appointment with a space combat shooter created for the EVE Online franchise. The interaction wasn’t so ambitious that I was controlling invisible cockpit sticks. Instead, I was using the DualShock 4 once again for much of my ship’s controls while I used the head-tracking to lock on to enemy fighters in anticipation of missile attacks.

Yet, it wasn’t the freedom of space flight nor my four kills that impressed me the most. My second “wow” moment came while I was waiting for my wingman to suit up. I was killing time by looking around my cockpit and noticed that by looking down, I could see my flight suit from the neck down. I was in awe when my view adjusted accordingly as I leaned forward and got a better view of my feet. It makes one wonder what you can see and do in the virtual cockpit of a car at a future trade show demo (hint, hint, Sony).