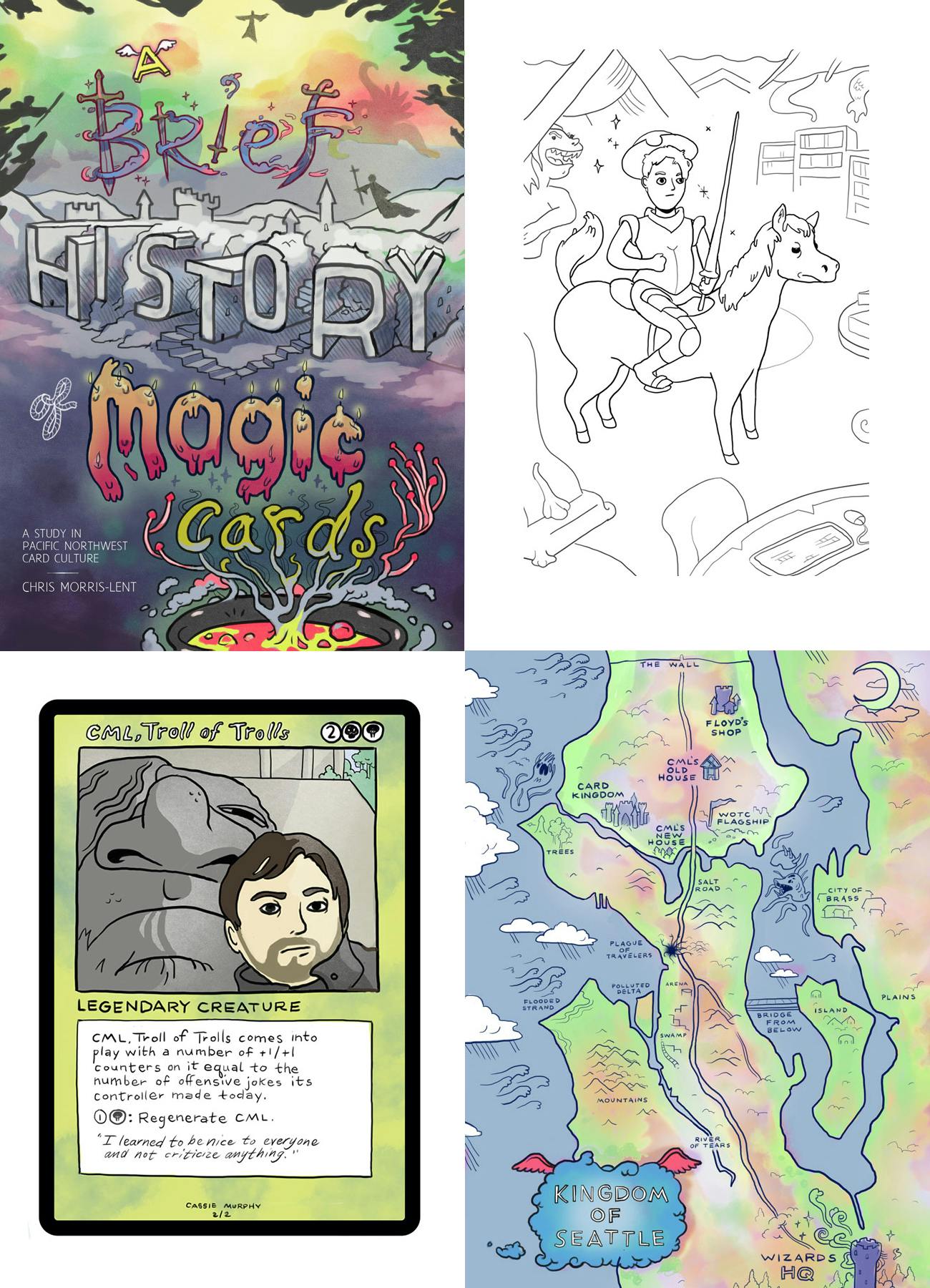

The following is an excerpt from A Brief History of Magic Cards, a new book exploring the the real-life, human history of Magic cards, currently being funded on Kickstarter.

The year is 1998, and I am 9. After weeks of self-conscious indecision, I have at last worked up the courage to tell Mike—my father, a real adult who knows the value of money and games involving exercise and teamwork—what Magic: the Gathering is, and why I want to play it.

“Will and Rob and Brian all do,” I explain, a nervous welter of sweatpants and sweat. (They don’t teach confidence or sales at magnet schools.)

“Then you should play too!” says Mike. “How do we get started?”

I sigh with relief. The hard part is out of the way.

We load up into the blue minivan and drive to 45th and University Way, in Seattle’s University District. Magic, at this point in time, is huge: I already feel like a latecomer. Since 1993, it has grown explosively, and made Wizards of the Coast (WotC)—holders of the copyright, keepers of the flame—very rich. They’ve invested some of this money in a flagship store, and it’s located, miraculously, a mile and a half directly south of my ancestral home.

Magic is dizzyingly complicated, extremely technical, and—to the layman—completely incomprehensible.

Though the store is long-gone, memories of its cluttered shop, its broken-down simulators, its huge Minotaur statue and steampunk vibe, will stay with me till my dying day. My most cherished recollection is of that first day where we parked the van, walked in, asked the clerk awkwardly for help, got awkward help, and then went home and played Magic, with house rules. I’d gotten over my compunctions and made peace with make-believe. I was a wizard.

I took to Magic naturally and obsessively. The game was good, and I wanted to be good at it; as I got better, it got better, until I was the best—of my friends. There was a brief period, near the beginning, when I would sometimes lose, to Will or Rob or Brian; after that, the house rules got closer to the real rules, and I never lost at Magic. This was due exclusively to spending more money on cards than my friends—and anyone can mistake that for being the best.

When we were in the know enough to shun the Wizards flagship and go to the local game store—or LGS—I’d eye the expensive cards that would make my deck unbeatable. Magic cards are beautiful objects—Walter Benjamin’s “aura” is alive and well—and the more expensive they were, the more I wanted them.

All the same, I’d usually spend my allowance on a “booster pack,” 15 random cards from a single set, instead. There is nothing like opening a sealed package of Magic cards, taking a moment to drink in that inky-fresh new-card smell, then flipping through the cards, one at a time, savoring the novelty and possession, and saving the excitement of the “rare” card, potentially valuable or powerful, for last. The LGS had a dingy atmosphere—dirty carpets, cramped space, questionable hygiene—which only added to the buzz. I wanted to play and talk about Magic all the time, and I looked up to the people who did.

There was a kid my age who was always at the LGS. He’d sit and sort cards with a thrilling minimum of parental supervision. Floyd, the shop’s owner, would pay him a pittance in store credit. The kid never spent it on boosters—always singles.

He had me outgunned.

“You wanna play?” he’d ask. He knew I couldn’t beat his Slivers deck.

“Nah.”

I knew it too. It was worth at least four times as much as my mono-White deck.

“Why not?” he’d say.

“I dunno,” I’d respond.

Then Floyd would upsell me on a card, and I’d buy it. They do teach confidence and sales in the real world, and both work well on magnet-school dorks that have no idea what they are. I look back at this past self, too meek and genteel to say no to a grasping pitch, and think of Don Quixote: terrified of dishonor, captivated by fantasy worlds, and utterly unschooled in the ways of this one.

Afterwards, in the van, my father would ask: “Is it really worth it to spend four dollars on a single card?”

I should have been asking him; it was his money.

People like to say Magic is a combination of chess and poker, but it’s more like Lego and Scrabble. As of 2016, there are over 13,000 unique cards—that’s the Lego part—and you arrange your favorites into a small deck, from which you pull seven at random and try to do something powerful or balanced while thwarting your opponent from doing the same—that’s Scrabble.

As for the specifics. Magic is dizzyingly complicated, extremely technical, and—to the layman—completely incomprehensible. The surface complexity is so formidable it might function as an upper bound on Magic’s market penetration. Even hardcore junkies sometimes get confused. The rules run to 36 pages (for the basic rulebook) and 207 pages (for the comprehensive version). As with board games, the only way to learn is to play, but I hope the following explanation clarifies more than it confuses:

I’ve spent dozens of weekends, hundreds of evenings, and over $15,000 on Magic.

In Magic, each player constructs a deck of 40 or 60 cards, draws seven cards from it, and can draw a card and play a “land” (resource) card every turn.

These lands can be “tapped” for “mana,” once a turn, to play “creatures,” which can “attack” the opponent, or “block” his creatures. The more mana a creature costs, the more powerful it is—usually, it will have greater “power” (attack) or “toughness” (defense). Other “spells”—“artifacts” and “enchantments”—go on the “battlefield,” alongside creatures, to interact with creatures, the opponent, or one another. “Planeswalkers” provide an effect every turn and can be attacked, like players. “Sorceries” provide a one-shot effect, as do “instants”—which can be played at any time, including the opponent’s turn.

The spells come in five colors—White, Blue, Black, Red, and Green.

The objective is to reduce the opponent’s life, from 20 to 0. You do this with creatures, usually. They are trying to do the same to you. When one of you succeeds, the game ends. Matches are best two out of three.

By contrast, the storyline of Magic is very simple. You are a wizard fighting another wizard. You are on one of any number of high-concept worlds called “planes.” The planes include “Germany” (Innistrad), “Eastern Europe” (Ravnica), “metal world” (Mirrodin), “adventure world” (Zendikar), “Arab world” (Rabiah), and “the real world” (Dominaria—Magic’s most iconic setting, used from Urza’s Saga to Scourge). Most of these planes have most of the high-fantasy creatures—elves, goblins, brushwaggs, humans. Most of them have heroes questing for something to save the world. You get the idea.

And so began my quest to join, conquer, and understand one of geekdom’s oldest, biggest, and weirdest subcultures. In the 18 years between now and then, I’ve spent dozens of weekends, hundreds of evenings, and over $15,000 on Magic. The last figure tells you why Magic exists: to serve its owners’ bottom line, while its players and employees, like Don Quixote, take refuge in fantasy narratives to pretend otherwise.

Unlike the nerd hobbies of yore, Magic offers some external rewards. Unlike spectator-friendly modern games, it doesn’t really have a professional class. It occupies a weird place between Dungeons and Dragons and, say, League of Legends: You can think of Magic as a cargo-cult version of poker. This makes it a perfect example of the compatibility of geek culture and capitalism, and the ups and downs of mixing them.

Before it was a massive franchise, Magic was an idea. In 1991, Richard Garfield was a math grad student at Penn. Geeky and beetle-browed, Garfield would earn his doctorate and start work as a professor at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. But Garfield had a fantasy, rare at the time and more common now, that his job could be his hobby. To that end, he’d been developing a board game called RoboRally, with byzantine rules and high production costs, since his days in Philadelphia.

It was this idea Garfield would pitch to Peter Adkison. Adkison shared Garfield’s fantasy: He was CEO of the Seattle-area gaming startup Wizards of the Coast. At the time, Wizards was a small company, nearly broke after defending itself from a lawsuit over the copyright for Dungeons and Dragons (D&D). Adkison, idealistic, enthusiastic, clad in nerd T-shirts, demurred: Garfield’s game would cost too much. But when Garfield suggested instead combining the play of card games with the collectability of baseball cards, Adkison immediately agreed. Work started right away.

Over the next several months, a team of designers, playtesters and artists worked feverishly to bring the game to market. As the production costs spiraled upward—this game would be much pricier than RoboRally—Garfield and Adkison doggedly scraped together money. Any number of minor events, like a retracted loan or an overdue supply order, could have strangled the game in the cradle. But Adkison pushed and pushed. Adkison allegedly didn’t care much for Magic, which made him, perhaps, the only person farsighted enough to see the idea to market.

Magic debuted at Origins, a gaming convention held that year in Fort Worth, Texas, in July 1993. The game generated intrigue and skepticism. There was nothing like it. It fit no genre. Could it really work? A lot of people would need to play, for a very long time, to do much more than recoup costs. There is an apocryphal story of Origins attendees getting free starter decks of Alpha, then throwing them out: Magic cards weren’t worth a spot in a swag bag.

All this would soon change. On Aug. 5, 1993, Wizards released Magic to the public. It was an instant success. Nerd conventions after Origins were overrun. The more people wanted cards, the more people wanted cards. The cardboard squares, 63 by 88 millimeters, with sweet art and names like Black Lotus, Ancestral Recall, and Craw Wurm, began to give off a glow of desirability.

The first run of cards would all be bought up, so Wizards printed Beta and Unlimited to supplement Alpha. Magic does have a role-playing element—you’re a dueling wizard, summoning creatures and lightning bolts to defeat your rival—but its popularity transcended its target demographic. Players of D&D and other tabletop games found themselves outnumbered. Gaming culture would never be the same. Magic got so big so quickly that even older people took note. For every dad like mine, there was one who saw the devil, and teens in Texas sometimes saw their collections burnt as offerings to a fair and just god.

From 1993 through 1995, Wizards released eight “sets,” or expansions to Magic: new cards, new game mechanics, new art. Some of these sets, like Antiquities and Legends, have stood the test of time: People still play with some of their cards, designed decades ago. The first expansion, Arabian Nights, was especially pivotal; Wizards had planned on releasing its cards with a new back, which would have made them distinguishable from original cards during a game.

But they didn’t. Arabian Nights cards have backs that look just like the backs of every Magic card ever printed, from Alpha to the present. And so a franchise was born. Wizards would do more than recoup costs. A lot of people would play a lot of Magic for a very long time.

Photo via Oliver Herold/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)