Speaking at a panel on Friday afternoon at the South By Southwest Interactive conference in Austin, Texas, the people behind a movie tentatively titled Dumping the Alien detailed their attempt to unearth the story behind one of the biggest urban legends in video game history.

The story starts in 1982. E.T. was everywhere. Steven Spielberg’s story of a gentle, candy-loving alien stranded on planet Earth was a breakout, blockbuster hit. Like so many before it, the flick spawned a veritable mountain of merchandise. There were E.T. shirts, E.T. hats, E.T. backpacks, E.T. actions figures, and E.T. lunchboxes. In addition to its record-breaking box office haul, E.T. pulled in more than a billion dollars on merchandising alone.

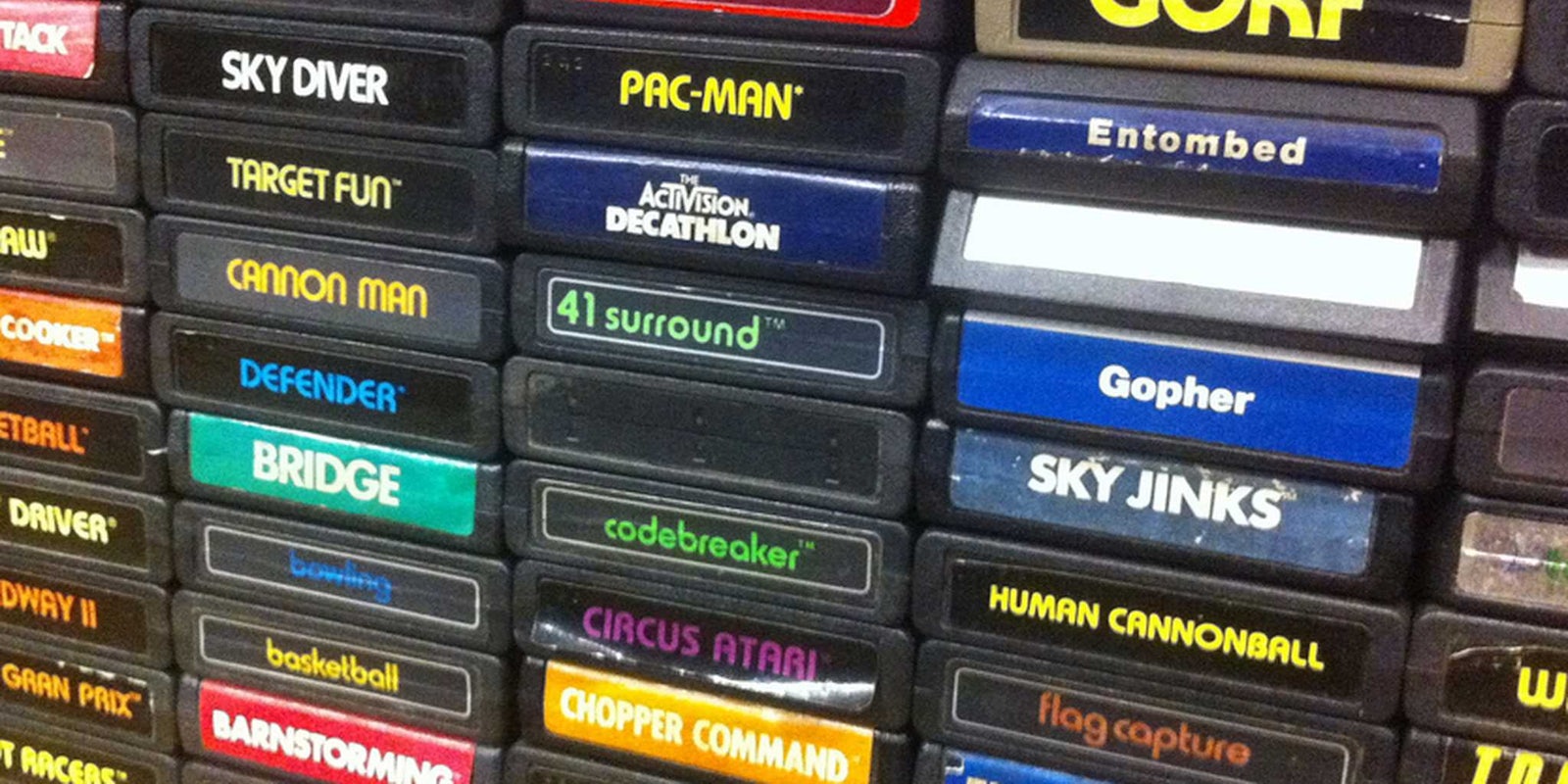

Seeing dollar signs, Warner Communications, the company that bought Atari in 1976, thought it could make a killing with a video game based on the movie. It tasked legendary game designer Howard Scott Warshaw with creating the game—one of the first created off a movie licensing deal. Though the usual development window for a game created in the early 1980s was eight to ten months, Warshaw was given a mere six weeks to come up with a product.

The game mainly consists of steering around a blob of green pixels that kind of resemble E.T.’s outline in an effort to collect green dots while evading evil scientists in white lab coats. In practice, the game primarily involves falling into pits and throwing the controller to floor in frustration:

‟Some say, considering Warshaw only had six weeks, the game could be seen as a masterpiece,” panelist Jonathan Chinn said with a laugh. ‟But, in reality, the game is absolutely unplayable. It is easily one of the worst games of all time.”

Chinn is the co-president of Lightbox Entertainment, a film production company that’s partnered with Xbox to create a movie delving into the literal wreckage of the E.T. video game.

Warner sunk a lot of money into the game, manufacturing over five million copies and accompanying its launch with a massive publicity campaign. The campaign did do some good, Atari was able to move about 1.5 million copies. But after the nascent video gaming community got wind of the fact that they were being sold a stinker of epic proportions, those sales quickly dried up. The game’s dismal performance contributed to Atari losing half a billion dollars in what’s been called ‟the great video game crash of 1983.”

What Atari did next has become the stuff of legend.

As the story goes, the company allegedly loaded all the remaining unsold copies of E.T. onto a fleet of big rig trucks and then buried them all in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico—only a few miles away from the site where the Manhattan Project detonated the first nuclear bomb. Copies of the game are now almost impossible to find.

Chinn wants to go to that landfill, dig up Atari’s deep, dark secret, and film the entire thing for posterity. He said he’s gotten official permission from the Alamogordo city counsel for the project and plans on beginning excavation within the next four to six weeks.

If they actually end up striking silicon gold and finding the trove of games, the Smithsonian has apparently indicated that it would love to get its hands on a copy for its archives.

Fellow panelist Mike Burns, CEO of the multi-media production company Fuel Entertainment that’s partnering with Chinn to develop the film, explained that looking into the aftermath of E.T.’s failure has the potential to provide insight into the downfall of Atari—a firm that once seemed to be headed for world domination.

‟Atari was poised to become the biggest technology company in the world,” Burns said.

‟Atari should have been what Apple became. They had the brains; they had the talent; they had the vision. They had a virtual monopoly over their industry and they employed some of the best minds in the business. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak both worked there. The company’s founder, Nolan Bushnell, was a visionary.”

Instead, shortly after the E.T. debacle, Atari began to sink into irrelevance, soon becoming outpaced by competitors like Sega and Nintendo.

‟Trying to bury your mistakes is always questionable,” Chinn insisted. ‟The way that they dealt with this bad product may be a clue as to why Atari failed.”

Photo by Clare McBride/flickr