Warning: This review contains minor story spoilers for Firewatch.

The most gripping part of my six-hour Firewatch playthrough was running for an evacuation chopper through a storm of dirt and smoke as a massive forest fire threatened to engulf me.

It also provided a sharp contrast to how emotionally divorced I’d felt during most of the game, on account of the way Firewatch keeps its characters at a distance.

Firewatch is about Henry and his summer job manning a one-person lookout tower in a forest in Wyoming. His primary responsibility is to keep watch for wildfires and alert the authorities if one begins. The game is set within the patch of forest for which Henry is personally responsible.

He interacts almost entirely with only one other character, Delilah, a 13-year veteran of the job stationed at a different tower. Henry can always see Delilah’s tower on the horizon, and he can only communicate with her via a handheld radio.

Henry has taken the isolated job to get away from a family tragedy. His wife, Julia, suffers from early-onset Alzheimer’s. Henry tried and failed to provide the care that Julia needed, and she was taken home to Australia by her parents, where they could watch over her properly.

We are told about all of this via a text-adventure-style prologue, intercut with shots of Henry driving and then hiking out to the lookout tower. The text adventure is literally a fill-in-the-blanks exercise, with the player determining some of the fine details as to how Henry met Julia, what their relationship was like prior to her falling ill, and how Henry handled her illness once it became advanced.

The intro effectively conveyed to me the sense of narrative ownership upon which adventure games depend, though I felt sure that the results of my choices would be purely cosmetic. I have also seen immediate family members suffering from Alzheimer’s, which gave me a touchstone by which to understand Henry’s situation.

I never felt as close to Henry again as I did during that introduction, however, which is ironic considering I was in his shoes for the rest of the game.

I appreciated that Henry isn’t the typical video game protagonist. He’s doughy. He’s awkward. He’s voiced by Rich Sommer, who played Harry Crane in Mad Men. Sommer’s performance is superb. He turns Henry into a character who sounds genuinely likable.

But if I had to describe Henry as a character, “awkward” and “likable” are the only two words that come to mind. Even after Henry began to disclose to Delilah the details about his relationship with Julia, I never felt like I was learning anything new about Henry. I was feeding back to Delilah what I already knew based on the intro.

While Henry felt underdeveloped as a character, he also felt genuine. Delilah, on the other hand, gave me so many eyebrow-raising moments that my suspension of disbelief was sometimes tough to maintain.

On the second day after Henry’s arrival at the watch tower, Delilah discovers that Henry’s wife had a Ph.D., and was an instructor at Yale. Delilah immediately makes comments about how being married to a teacher must be sexy. The next day, Delilah is asking Henry to describe what he looks like, and when he divulges that he has facial hair, she says “Now you have my attention,” and makes a sexy growl.

Imagine a woman posted at an isolated, one-room watchtower, who is a two-day hike from civilization, making salacious comments to a man she has never met. This sounds like a female character being written by a man.

Delilah coming on to Henry—or even pretending to—was even more difficult to believe given the events a day earlier. Henry finds a note left by a pair of teenage girls that he shooed from the forest for creating a fire hazard. The note accuses Henry of attacking them and threatens that the girls will be calling the police.

When Henry relates the note to Delilah, she asks him whether or not he did assault the girls. When Henry acts offended, Delilah says something along the lines of, “I’ve only known you 24 hours. You could be crazy.” This, then, is the man she makes advances to the following morning?

I never got over my reaction to these scenes. It might have been different if we ever learned anything about Delilah, like where she came from, or why she took such an isolated job, but Firewatch never divulges these details.

Whenever Henry is investigating a location and the player mouses over an object of relevance, the player is prompted to raise the radio and call the information in to Delilah. The fact that this is offered as an option suggests that not every item is important enough to report.

Technically that’s probably the case, but I never felt like I could skip any of those call-ins without running the risk of missing something important, because a substantial portion of the exchanges between Henry and Delilah over the course of Firewatch are triggered this way.

Three hours into the game, when the story finally began to kick in, I found myself wishing that Henry could relay multiple points of information about a new location in a single radio call, to cut down by at least half the number of times I had to find a thing, raise the radio, tell Delilah, get a one-line response, and go back to looking for another thing.

I get that adventure games suffer from a lack of interactive elements compared to other genres, so developers look for every opportunity to give the player something active to do.

But when I felt like I had to click on everything because I wasn’t sure what was or wasn’t important, it began to feel like it was stalling the narrative.

I had a similar issue with navigating the environment. The Wyoming forest in which Firewatch takes place is picturesque and so well sculpted that I was constantly lulled into thinking it was an open world, albeit a small one, through which I could wander.

Then, when I would try to take what looked like a legitimate shortcut through the woods between different parts of a trail, I’d usually hit an invisible wall.

It makes sense that I wouldn’t be allowed to throw myself off a cliff and utterly break the flow of the narrative. Not being allowed to duck under a fallen tree when I can clearly see the path beyond makes less sense.

I understand that Firewatch locks the player onto certain paths in order to trigger dialogue sequences between Henry and Delilah, but having my path so strictly prescribed at times when I was looking at a forest begging for exploration was frustrating.

I also got tired of the constant need to press the spacebar to climb over a rock or up a small rock staircase, or drop down from a rock shelf. Rappelling up or down cliff faces wasn’t so frequent an occurrence it became uninteresting, but all the repeated, minor interruptions felt arbitrary.

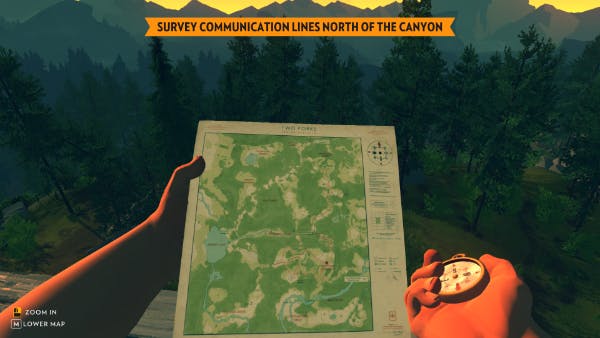

Henry is equipped with a compass and a map to help him navigate the forest, but I frequently had trouble matching the information on the map to the actual layout of the ground nearby.

Imagine holding a map up to your face, walking for a minute or two, holding the map up again, and referring to your compass to make sure you’re facing the right direction, over and over again.

Being in a hurry toward the end of the game may have accounted for a healthy share of my frustration, but all of these frustrations combined made me resent having to backtrack over the same trails over and over again.

I was in a hurry because I figured the slow early start, the tediousness of clicking on and reporting every detail, and the frustration of fighting the environment would be rewarded with some sort of narrative payoff.

Instead it turned out that the plot was one giant misdirect whose resolution felt disappointing. Firewatch’s ending also failed to lend any emotional weight to Henry and Delilah’s relationship. That made me question whether Henry had forged a relationship with her at all—which made me wonder why it was worth talking to her for six hours.

To be fair, Firewatch is trying to pull off a very difficult task. The modern incarnation of the traditional adventure game—think everything developed by Telltale Games—dips deeply into the same toolset employed by film and television from shot composition to editing.

First-person adventure games like Firewatch deny themselves the bulk of those techniques by essentially turning the camera into a GoPro strapped to the protagonist’s head.

When a first-person adventure game plays with time and space like That Dragon, Cancer or when it contains fantastical elements like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, the developer buys a little leeway, but not much, when it comes to story and character. First-person adventure games that adhere to the strictures of reality abandon that leeway, and story execution becomes even more crucial.

At the end of Firewatch I felt I knew nothing more about Henry than I’d learned six hours before, during the text-adventure intro. Henry’s character arc turns out to be him grappling with whether or not he should go visit his wife in Australia. If he was thinking about this throughout Firewatch, I missed it entirely—his talking about the decision with Delilah at the end of the game felt apropos of nothing. Delilah, as I mentioned, remained a blank slate, so I had nothing to think about in terms of how either character grew. Not being able to picture an arc just made the character feel generic.

The quality of Sommer’s voice performance was just enough to prevent Henry from becoming forgettable, but when all you have is two characters and a forest, there’s little room for error when it comes to making sure those characters connect.

Disclosure: Our Steam review copy of Firewatch was provided courtesy of Campo Santo.

Illustration via Campo Santo.