As the Marvel Cinematic Universe enters its third phase, we delve deeper into some lesser-known corners of Marvel canon—beginning with Doctor Strange and the world of magic.

Doctor Strange’s origin story is more like a martial arts narrative than a traditional superhero arc, because it’s all about learning a new skill from a wise mentor. Introduced as an acclaimed but arrogant surgeon, Dr. Stephen Strange decides to learn the mystic arts after his hands are permanently damaged in a car accident. His journey takes him to the Himalayas, where he studies magic with a master known as the Ancient One, learning how to perform magical spells and travel to other dimensions.

Throughout most of Marvel canon, Doctor Strange is known as the Sorcerer Supreme, Earth’s magical guardian. Armed with his Cloak of Levitation and the Eye of Agamotto (a powerful amulet with a wide range of uses like a magic wand), he deals with villains who are too weird or supernatural for traditional superheroes to handle.

Steve Ditko and psychedelia

Created by artist Steve Ditko in 1963, Doctor Strange is characterized as aloof and occasionally pompous, a serious-minded figure whose priorities lie beyond the mundane realm of characters like the Avengers.

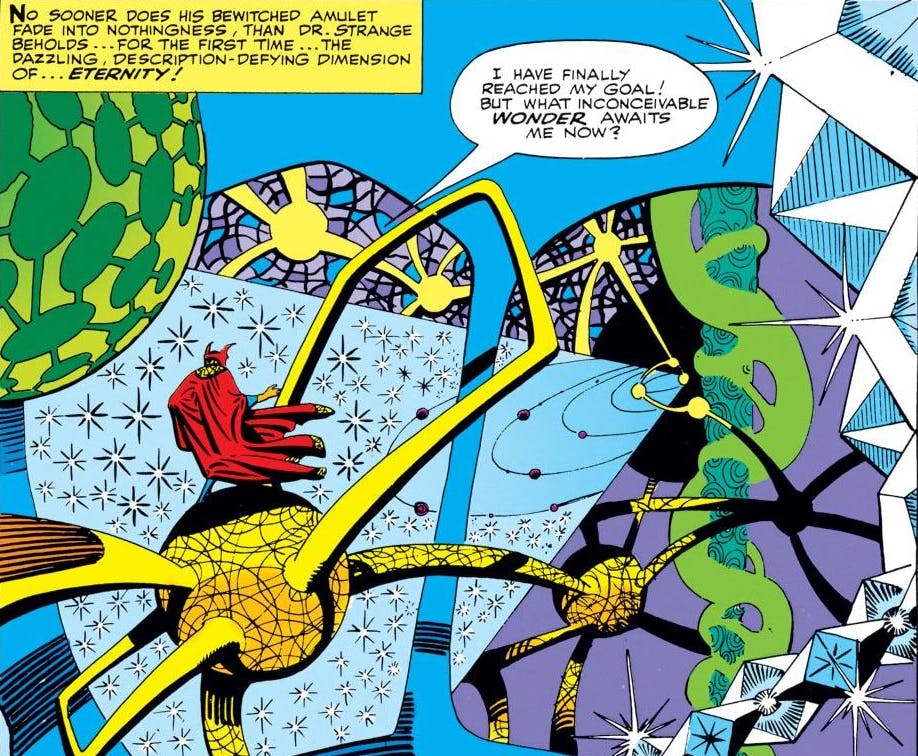

Rather than being character-focused like Spider-Man or Iron Man, Doctor Strange’s popularity is defined by the art and worldbuilding of his earliest comics. During the brief period he was in charge of Doctor Strange, Ditko’s art evolved from “innovative for a superhero comic” to downright psychedelic, featuring surreal alien landscapes, bizarre monsters, portals to other dimensions, and gorgeously visualized magical spells. His iconic work is clearly visible in the movie, from the glowing gold design of Strange’s magical sigils, to the gravity-defying urban scenes where buildings seem to fold in on themselves.

Thanks to Ditko’s art and the comic’s mindbending supernatural themes, Doctor Strange accidentally captured the zeitgeist of the ’60s. Fascinated by psychedelia, “Eastern” mysticism, and paranormal ideas like out-of-body experiences, counterculture kids gravitated to the world of Doctor Strange. And throughout that early period that defined him for years to come, you could only find him by flipping to the back of a cheesy adventure comic starring the Fantastic Four.

The origins of Doctor Strange

Doctor Strange began his life in the anthology comic Strange Tales, where he only warranted the final third of each issue.

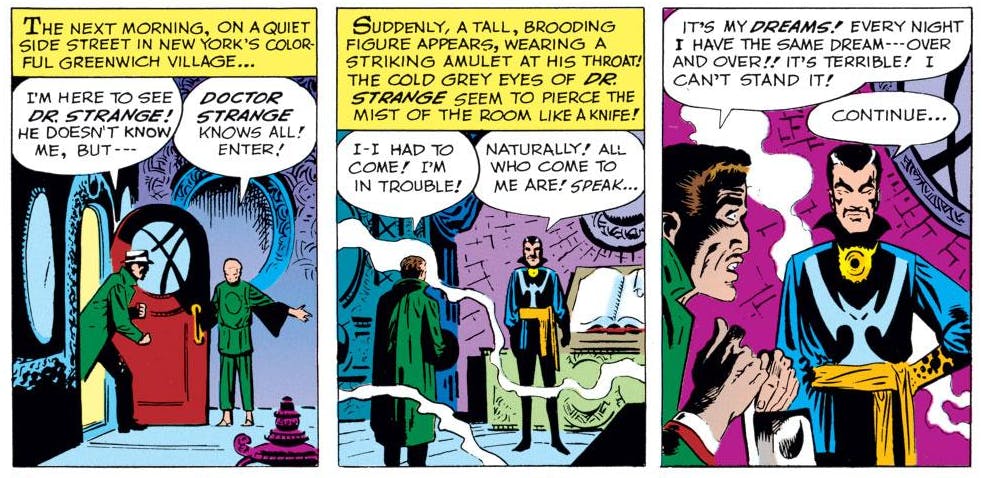

Instead of an origin story, his introductory issue (Strange Tales #110) establishes the formula for his monster-of-the-month adventures. Someone comes to Strange’s house in Greenwich Village, tells him about a mystical problem, and Strange helps him out—in this case by entering a man’s dreams to confront a menacing figure named Nightmare. (Sandman fans may already recognize some early influences here.)

This short story introduces many central aspects of Doctor Strange canon, such as the Eye of Agamotto, Strange’s loyal manservant Wong, and the role of the Ancient One as Strange’s mentor. The villainous Baron Mordo shows up in the next issue, introducing another essential element of Doctor Strange comics: interdimensional battles.

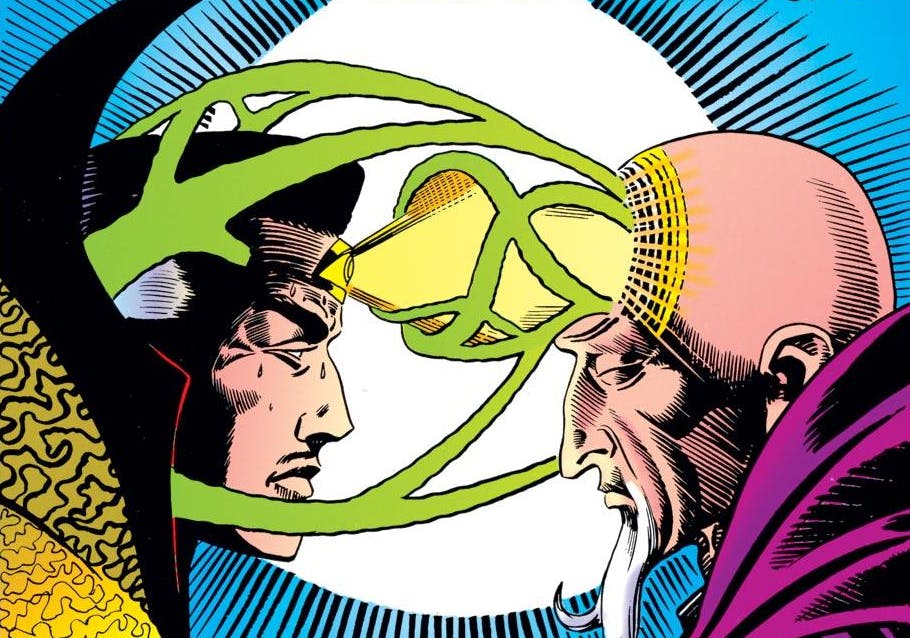

Ditko cemented his legacy in Strange Tales 130-146, a lengthy storyline where the comic moved from earthbound magical duels to an epic conflict with the tyrannical Dormammu, ruler of the Dark Dimension. Some fans characterize this arc as an early example of a serialized graphic novel, although the storytelling is pretty weak by modern standards. Events are painstakingly announced in dialogue and thought bubbles, and characterization is thin, but the art is wild and the concepts behind the main story—telepathic battles, Escher-like landscapes, one character who is basically an entire universe in humanoid form—are far beyond the typical content of a 1960s superhero book.

A series of new creative teams covered Doctor Strange until the late ’80s, expanding the world created by Ditko. Writer Roy Thomas and artist Gene Colan added more elements of horror and dark magic during the 1968-69 series, moving more toward the demonic fantasy of DC’s supernatural books (Swamp Thing, Constantine) than the philosophical mysticism of the early ’60s.

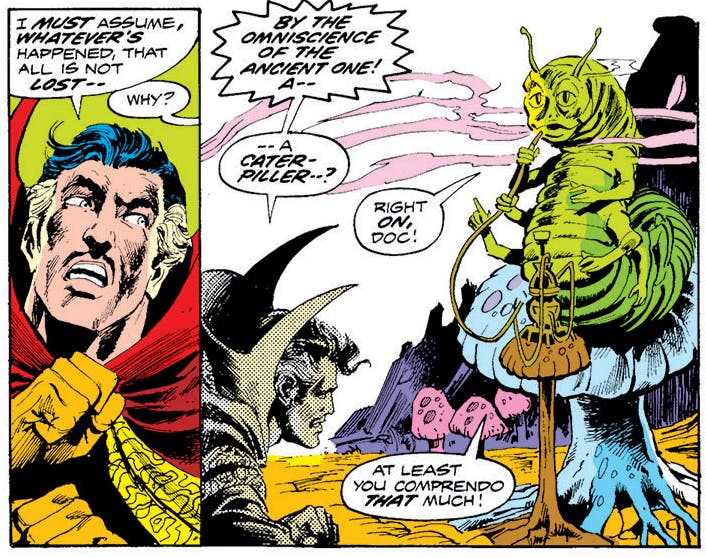

By the 1970s, the creators were leaning into the stoner angle of the comic, with a more knowing attitude than Ditko. Issue #1 literally includes a scene with an Alice in Wonderland-like caterpillar smoking a hookah pipe.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that Doctor Strange doesn’t age as well as some Silver Age comics. While the Ditko era is beloved for a reason, many of the early Doctor Strange comics are sexist, racist, or both.

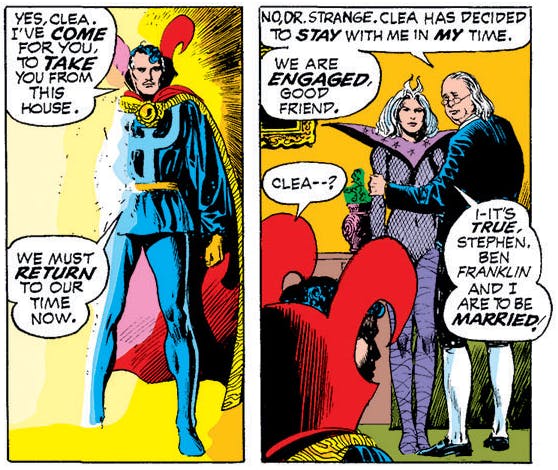

Strange’s relationship with his girlfriend/apprentice Clea seems hopelessly unbalanced to modern eyes, and Clea’s role regularly enters damsel territory despite her magical powers. In one comic, Strange leaves her alone with Benjamin Franklin for like 20 minutes (don’t ask), and she promptly falls in love with Franklin and sleeps with him, only to discover he’s an evil wizard in disguise.

Meanwhile, Doctor Strange‘s roots in “Eastern” mysticism are, in retrospect, a rather clumsy attempt at cultural appropriation. In the words of Doctor Strange movie director Scott Derrickson, Strange’s mentor the Ancient One is “a very old American stereotype of what Eastern characters and people are like.” In a similar vein to Marvel’s Iron Fist, the premise of Doctor Strange relies on the idea that a white American man can, after a brief period of training, become better at a specific martial art than his Asian tutors, who are then relegated to background roles.

The 1980s

This is when Doctor Strange began to get personal.

While Doctor Strange‘s art and fantasy worldbuilding are consistently interesting, his early characterization wasn’t very complex, and his story arcs often lacked emotional weight. All those interdimensional duels tend to feel like private feuds between Strange and his enemies, disconnected from any human impact on Earth.

Comics like the 1987 Strange Tales series tackled this by going deeper into Strange’s role as a powerful yet distant figure in the Marvel Universe, exploring his moral ambiguity and occasionally ruthless attitude. Later, the one-off Doctor Strange and Doctor Doom: Triumph and Torment (1989) expanded on the world of magical practitioners in the Marvel universe, with sumptuously gothic art by Hellboy‘s Mike Mignola.

The 1990s and 2000s

Doctor Strange‘s ’90s series saw him lose his powers and team up with various superheroes, followed by a period where he mostly appeared in team comics—a magical interloper in the sci-fi world of the Avengers. But one book from this period is a must-read for new fans: The Oath, written by Brian K. Vaughan (Saga, Runaways) and drawn by Marcos Martin.

This standalone miniseries introduced a new way of looking at Doctor Strange. The dialogue is snappy, the narrative doesn’t take its protagonist too seriously, and we finally get a more nuanced look at Strange’s relationship with his manservant Wong. It’s often unclear what motivates Wong to dedicate every waking moment to Stephen Strange, so The Oath attempted to balance this dynamic by illustrating the depth of Strange’s loyalty in return.

After Wong is diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor, Strange flings himself into a rescue mission that combines his medical expertise with his career as a sorcerer. Supported by Night Nurse (Rosario Dawson in Marvel’s Netflix franchise) as a down-to-earth contrast to Strange’s eccentric lifestyle and old-timey style of speech, The Oath ties together the strengths of the earlier comics with a more self-aware sense of humor.

The New Avengers era

From 2013-2015, Jonathan Hickman wrote Avengers and New Avengers as two interlocking storylines, leading up to the 2015 Secret Wars miniseries, which can be read as a standalone graphic novel.

Despite being an ensemble story, Hickman’s New Avengers may be the most narratively interesting Doctor Strange comic to date. As a member of the Illuminati, a powerful and secretive organization including characters like Iron Man, Black Panther, and Namor, he tries to avert a series of global catastrophes called “incursions.” These collisions between alternate Earths can only be prevented by destroying another universe, meaning the Illuminati must effectively commit genocide to protect their own world. As this decision takes a moral toll on each of the characters, we get a better look at Stephen Strange’s detached, “ends justify the means” attitude, set apart from his more relatable allies in the Avengers.

In the follow-up, Secret Wars, Strange actually becomes the right hand man of Doctor Doom, a role that further explores his attitude to power.

Doctor Strange in 2016

Like the 2016 Power Man and Iron Fist comic (just in time for the Netflix franchise), Marvel has launched a new Doctor Strange series.

Written by Jason Aaron and drawn by Chris Bachalo, the new Doctor Strange is a self-deprecatingly funny adventure story. Stephen Strange is intentionally portrayed as a little pompous and melodramatic, striding through New York amid otherworldly monsters only he can see. Working out of his house on Bleecker Street, he’s back solving magical problems for walk-in customers in New York City.

It’s nowhere near as weird as the earlier comics, but that’s OK. In the intervening decades since Steve Ditko, that original counterculture role was taken up by more experimental comics like Sandman and The Invisibles, leaving Doctor Strange to enter the mainstream realm, and eventually become a Hollywood brand.