Give players the choice to be good or evil in a video game, and many will embrace their dark side, right?

Maybe not. Game makers at the 2015 Game Developers Conference on Tuesday learned that pure-evil decision making might not be that appealing after all.

Amanda Lange, a technical evangelist at Microsoft (she shows developers ways they can use Microsoft products to make video games) is a fan of role-playing games. She was curious about whether and why people chose to make evil decisions when given moral choices in games. Hosting a conference panel, Lange shared the results of some anecdotal research she did to figure out why players eschew evil choices.

“I always play the bad guy in these games, almost always,” Lange said. “I just want to push the ‘evil’ button and see what it does. And I felt like a lot of people, in conversations I had, they were just totally lost, and didn’t know why anyone would do this.”

For instance, the role-playing game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim has different guilds and colleges for players to join. One of them is the Dark Brotherhood, a guild of assassins. Joining the Dark Brotherhood requires players to kill people, and in Lange’s experience, people she talks to about Skyrim wouldn’t chose to that guild.

“It’s the best quest chain in the game, right?” Lange said to the audience. “It’s the most fun, most polished-feeling content, I thought, for whatever reason.” Lange’s friends chose not to engage with the Dark Brotherhood quests because “they were the bad guys.”

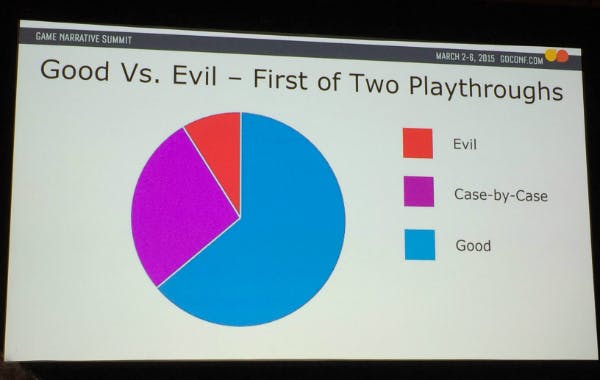

Lange created an informal survey on SurveyMonkey to ask players about moral choices in games. Of about 1,000 responses, the results said that only 5 percent of players, when they only played an RPG once, chose to follow the path of evil. Over half of these players choose good options, and the rest made their decisions on a case-by-case basis.

When players went through an RPG multiple times they were more likely to try evil choices, but the majority of players still choose to be good guys during a second playthrough. The problem is that most of the evil choices in video games tend to be “pure” evil, with no redeeming quality to the choice. Players in the survey felt that evil ought to be punished, so why would they choose to be evil?

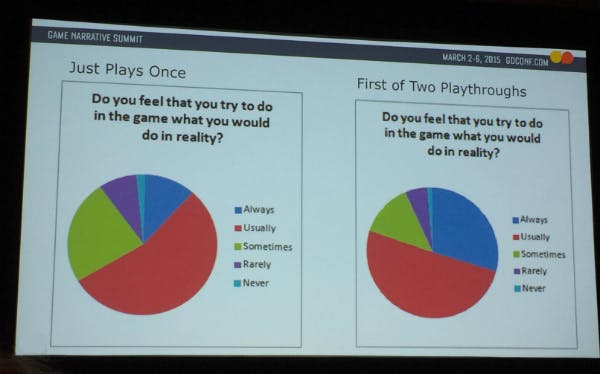

The challenge is getting players to engage in what Lange referred to as “identity tourism.” Players overwhelmingly made moral choices in video games that reflected their real-life morality. Even in a game like Grand Theft Auto V, which encourages criminal mayhem and expresses no value for the lives of other people on the street, respondents said they didn’t like having to torture someone in one of the narrative scenes. Players had no choice to opt out of the brutality.

In the “No Russian” level of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, where a cell of Russian terrorists attempt to set up an undercover CIA officer by carrying out a mass execution at an airport, players overwhelmingly chose not to fire on civilians. In BioShock, players didn’t like harvesting DNA from Little Sisters, the little girls biologically altered to create the genetic material that fueled players’ powers, even if harvesting the Little Sisters led to the player become immediately more powerful.

The key to encouraging players to experiment with morality is offering moral choices that aren’t black and white. Games like Dragon Age and Fallout: New Vegas offer choices that are less about good and evil, and more about choosing alignments with different factions, or trying to impress different characters. Moral choices connected to factions may encourage more experimentation with different kinds of choices.

“Walking Dead [from Telltale Games] came up a lot,” Lange said. “Instead of doing an evil thing because you’re going to get more gold, you do an evil thing because you’re really mad at [someone].” When choices in The Walking Dead were obviously good or evil, two-thirds of the players chose to make the good choice. The more ambiguous the choices, however, the more player’s decisions were split almost 50/50 in which decision they made.

To punch or talk down another character who has lost his composure, or choosing whether or not to save a character from an impending zombie attack when the character had proven to be a potential liability, were the kinds of choices that inspired more variety from the players, in how they chose.

There’s a lot of work to be done, in order to understand players’ moral choices. “I just don’t think that pure data tells the whole story necessary,” Lange said. “I think maybe a combination of both data and interviewing players to see what works for them and what doesn’t work. I think that gives you a better idea.”

One conclusion from Lange’s informal study seems clear, however. “Players generally do not find pure evil tempting.”

Illustration by Jason Reed

Our editors curate the top news and analysis on topics that matter. Sign up for the Daily Dot digest newsletter.