It’s like something out of Outbreak or The Hot Zone: Aid workers in awkward biohazard suits maneuvering around a pop-up hospital and isolation unit, fighting a deadly virus in crude conditions.

That’s the current reality in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, where a fast-moving outbreak of Ebola is sweeping through the population. With a death toll approaching 350, Doctors Without Borders has declared the epidemic “out of control” and is begging for help; the organization has come up against the limits of the technology, personnel, and equipment it can offer. Everything is on the ground, and there’s nothing left to give. The organization warns that unless neighboring nations and other international groups take action, Ebola could spread across all of West Africa.

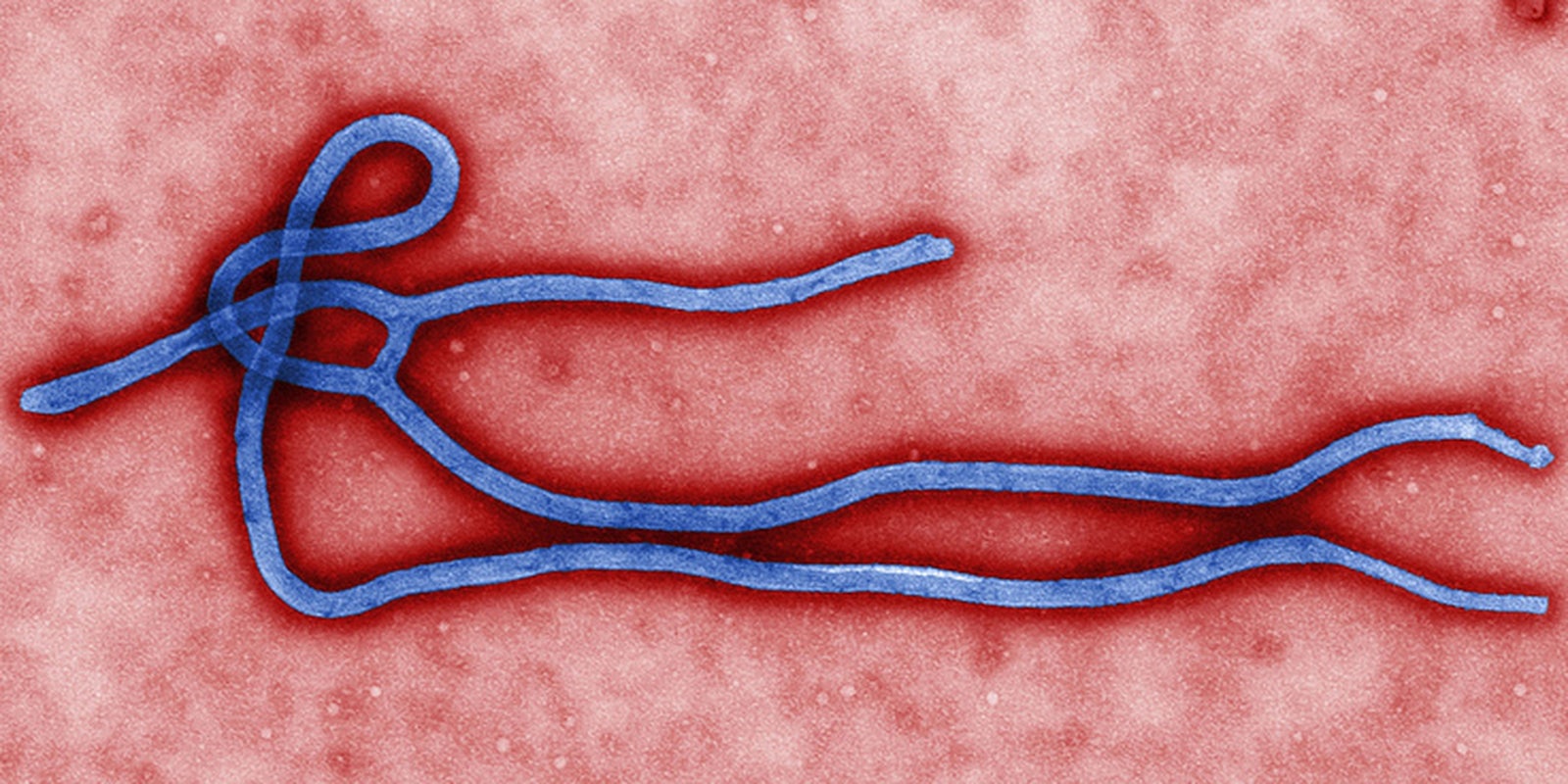

Ebola is endemic to the region, and periodically flares up, infecting small groups, causing a handful of deaths, and then dying back down again. Its mortality rate is somewhat exaggerated, but even for patients who survive, it’s not a pleasant experience. Ebola causes a spiking fever, internal bleeding, headaches, muscle and joint pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Eventually, patients experience organ failure; approximately 60% are dying in the current outbreak.

In this case, a particularly vicious strain of the virus began spreading in populated areas nearly six months ago, working its way over to neighboring nations with surprising speed. As the disease spread, governments were slow to act, even in response to direct recommendations like suggestions for road closures to keep the virus contained. Family members distrustful of aid workers, doctors, and the medical establishment compounded the problem by “rescuing” patients who had been kept in quarantine, spreading the virus as they brought loved ones home.

Epidemiology is a fascinating and complex blend of medicine, technology, and basic boots on the ground work. Laypeople are often fascinated by infectious disease, particularly in the case of conditions like Ebola, which are viewed as mysterious and frightening in the West, which has never experienced an outbreak (lab accidents have occurred, but they were quickly contained). We marvel at how a tiny organism can inflict so much pain and misery, and how quickly it can spread through a population, wreaking devastation in its wake.

Epidemiologists are like firefighters, responding to the scene of an outbreak to contain it, suppress it, and clean up afterwards. But instead of fighting flames, they’re fighting disease, which complicates matters. Fire is a clear, simple, obvious enemy. Epidemiology requires careful surveillance, study, and research—it can take weeks to determine the cause of an infection, let alone why it’s spreading. Even in the case of known conditions like Ebola, confusion on the ground and government resistance to help may lead to delays in diagnosis and action.

Which is where the technology aspect of epidemiology becomes so important. Within the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintain the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS), which includes a detailed reporting service that monitors public health issues. When two isolated events that appear uncorrelated are both logged in the system, it notes them, and it keeps compiling the data until a pattern emerges. That’s one of the reasons the CDC can respond quickly to epidemics and hit the ground with a substantial body of information right from the start.

Such surveillance is widely used with STIs and HIV, allowing public health agencies to keep an eye on troubling patterns in disease transmission and spread. But it can also be useful for tracking food poisoning, mystery infections, and more. Similar surveillance is in place at the World Health Organization to look at global public health trends and identify the signs of fires when they’re still small, and easy to put out.

Putting out fires with technology, though, requires the cooperation of global governments, along with a strong supportive infrastructure and maintenance. In West Africa, attempts to contain the Ebola outbreak are being hindered not just by a lack of personnel and facilities—or by government sluggishness—but by limited access to technologies that could help groups like Doctors Without Borders and the CDC (which responds internationally, not just within the U.S.) contain the epidemic.

It can take mere weeks for a disease to gain a foothold and start spreading, and this is the crucial period when surveillance makes a difference. There’s a reason “Patient Zero” is so important—this initial point is the hinge upon which the outcome of the epidemic falls. Where did she go?What did she do? What did she eat, drink, or handle in the days before her illness and/or death? How are other patients linked to her?

Nations without an adequate technological defense against disease are sitting ducks for aggressive outbreaks, not just of known infections like Ebola, but entirely new diseases.

However, addressing the gap between countries that have and have-not is daunting, because the implementation of surveillance systems and supporting technology is a demanding task. Supporting infrastructure, including personnel to train doctors, nurses, and other health officials in the use of the system, is critical. Programmers and staff to maintain a surveillance system so it keeps functioning are critical. Simple basic infrastructure like communications systems is required to ensure that data is quickly and accurately spread from site to site, and to central compilation locations where trained epidemiologists can review data, track trends, and activate response teams as needed.

An effective surveillance system could be the starting point for an empowering science and technology aid package for a host nation. As the West has learned through years of painful experience, dropping technology in and hoping for the best doesn’t work, as equipment quickly languishes, ends up on the black market, or isn’t used to its full potential. To protect nations—and the world—it’s critical to have an international public health surveillance system with deep roots in every country, not surface WHO and CDC support that can’t logistically keep up with the demands of the international community.

During the first known Ebola outbreak in 1976, CDC officers were forced to communicate by walking for miles between missionary stations and waiting patiently to use their radios—and, in turn, they had to count on the missionary down the line to pass their message on, for the recipient to pass it along, and so forth until the final destination. This kind of fumbling in the dark led to catastrophic delays. Even with first responders on scene doing important medical work, without technology, it can be difficult to get the better of infectious disease.

Photo via theglobalpanorama/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)